It is not an exaggeration to say that the Western Balkans future relies on the participation of its diaspora in their countries of origin. The diaspora’s potential to creatively introduce to their country of origin the experiences, knowledge, networks, and visions gained abroad is enormous and arguably the key to the region’s success. Having benefited from opportunities while working abroad, most diaspora members still have a strong commitment to their homeland, willing to share their knowledge and experience with their fellow citizens.

However, for Western Balkan states to enjoy the full benefits of international diaspora dynamics, governments must create distinct and transparent emigration structures that allow for swift transfers of information between communities as well as for benefits to be portable between the diaspora and home countries. In other words, to unlock the diaspora’s potential, resources, and capacities to assist their home region’s development, they need to be included in all relevant policy dialogues. Policy architects must create a clear path for diaspora to have a say in important and strategic decision-making at the state level, which will also help create an encouraging and positive environment between governments and their diaspora.

This undertaking is a considerable task for any government, but the sooner the Western Balkan governments start tapping into diaspora’s potential, the sooner the benefits can be expected. As seen elsewhere, diaspora policies show true results only many decades later.

To illustrate the importance of having close connections with diaspora and to show how a departure of skilled people can have immediate negative consequences in the countries of origin, this paper will focus on an ongoing crisis caused by the COVID-19 global pandemic and its impact in the countries that face significant departures. Specifically, by highlighting the mass exodus of medical staff, this paper argues that Western Balkan governments should provide opportunities and incentives for talented citizens to stay in the region, while also and maintaining strong connections with those who have left.

“Our health system is heavily burdened. If the virus continues to spread at this rate, we will not be able to provide adequate and timely health care to all who need it.” This was an appeal from Marko Lugonja, a General Practitioner and an abdominal surgeon in Republika Srpska in Bosnia and Herzegovina in June 2020. Similar appeals were heard elsewhere in the region.

While the number of infected people is growing daily, Western Balkan doctors warn that they are overwhelmed and that the healthcare system is overburdened: “We have been in the red for a long time,” stated young doctors working at the Clinics in Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

With over 300 new COVID-19 cases per day in August 2020, and hundreds of dead by now, countries in the region, especially Serbia and Bosnia, truly struggle with handling the effects of the pandemic. Hospital capacities are full, there is a shortage of medical staff, and the healthcare system’s capabilities are overstrained.

For experts of the region, the Western Balkan healthcare system’s inability to cope with effects of the global pandemic is unsurprising. For more than a decade leading up to the pandemic, the quality of healthcare in the region has been declining sharply, as a result of outdated and poorly maintained equipment and medical facilities, but also because of a drain of specialized and highly qualified doctors. Massive emigration of highly skilled doctors has been a challenge for the region even before the pandemic; COVID-19, however, exposed the gravity of the situation.

With a donation from the European Union (EU), partial measures have been taken to boost the capacity of the health sectors throughout the region during the first months of COVID-19. In Albania, for example, funding amounting to 3.5 billion lek ($1 million) has been provided to purchase personal protective equipment (PPE) for health care workers. Bonuses of €1,000 have been added to the salary of medical staff, and €500 to salaries of medical workers. National governments have also reached out to all available medical staff. On March 10, President Ilir Meta called for retired Albanian doctors to re-enter the workforce. Salary raises and bonuses were offered to health workers and medical students, and doctors in retirement were asked to return to work. Similar pleas have been made in Bosnia, Serbia, and the rest of the region, where governments have been desperately looking to provide enough medical staff. However, the truth is that there is a limited number of available doctors, nurses, and medical workers left in the region, and those who remain, may also be thinking about emigrating.

Exporting medical staff

The healthcare of Western Balkan citizens is maintained through a mandatory health insurance scheme organized through a network of healthcare institutions. It has been under-funded for years and consequently the standard of public healthcare has declined. Healthcare professionals are well trained, but they are let down by often poor or ageing equipment and low salaries. As such, the flight of doctors to Western countries is an increasing problem. Although the countries of the Western Balkans are not in the EU, it is relatively easy for doctors, nurses, and healthcare professionals to move to the EU for far better pay and conditions.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the National medical workers’ Association reported that around 300 highly qualified doctors left the country in 2016. In September 2019, the Zenica Cantonal Hospital in Bosnia issued a public statement saying that the town of Zenica, with over 100,000 inhabitants, no longer has neuro-paediatric medical care available. At the time of the announcement, a large number of children had scheduled appointments for check-ups, resulting in their examinations being delayed until further notice.

The flight of doctors to the West in recent years has been documented in every former socialist country from Southeast Europe and the Balkans. Doctors from Poland, Romania, Moldova, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, North Macedonia, Albania, and Kosovo are emigrating by the thousands.

Between June 2013 and March 2016 some 4,213 Bosnians took up jobs in the German health care sector, bringing the total figure of Bosnians employed in this sector in Germany to 10,726. Data from the German Employment Agency also show that in March 2016, 1,102 Bosnian doctors were employed in Germany, representing an increase of 20% during the period from June 2013 to March 2016. In recent years these numbers rose sharply and it is estimated that for every six doctors in Bosnia, one works in Germany.

A recent study carried out in Albania by the non-profit organization “Together for Life” and the Friedrich Ebert Foundation found that 78% of doctors wanted to leave Albania, with 24% wanting to do so immediately. The main reasons cited in the study were lack of professionalism in the workplace, insufficient remuneration, and poor working conditions. While in Kosovo health workers could at best expect to be paid a few hundred euros per month, in Germany, their initial monthly salary is €2,000. The monthly salaries for doctors at the University Clinical Centre in Pristina, Kosovo’s biggest hospital, total a mere €632 for a doctor and €403 for a nurse.

The National Medical Council of Serbia has been issuing around 800 certificates of good standing per year. In Kosovo, the Federation of Health Workers claims the country lost 400 medical staff in 2013 alone, with an upward trend continuing in subsequent years. In North Macedonia, estimates are that about 300 doctors left in 2013 and 2014.

In the words of Harun Drljević, President of the National Medical Council of the Bosnian Federation, “The EU countries are getting ‘ready-made’ medical doctors without investing anything in their education and training. Ready-made and for free! This is a great gift for the health systems of the EU countries.”

Even prior to the COVID-19 crisis, the consequences of the health workers’ exodus were visible on the ground. Having no adequate replacement for them results in inadequate or simply non-existent health care services in these regions. Further, the emigration of health workers leads to sectorial underdevelopment, which is especially visible in peripheral regions and among the elderly, children, and women. The flight of doctors affects the capacities of the health systems that they leave behind, pushing those systems to the point of collapse, but also results in the loss of health services, a drop in the quality of health provision, loss of mentorship, research, and supervision.

The problem has been loosely recognized at the EU level and brought up in few discussions. At the same time, however, the EU greatly profits from this emigration. Germany, the wealthiest economy in the EU, is among the top benefactors of this trend. Today, Germany’s new health care plan projects use newly allocated funds to train people abroad and prepare them for health care work in Germany. Nine million euros will be used to train additional people in other sectors to come to Germany. Kosovo, North Macedonia, Bosnia, the Philippines, and Cuba are routinely listed as possible cooperation partner countries. This project comes as no surprise given there are at least 36,000 currently vacant health worker positions in Germany, and 15,000 of them are in senior citizen homes. Additionally, the number of people in Germany in need of these services is predicted to increase from 2.86 million to 4.5 million by 2060.

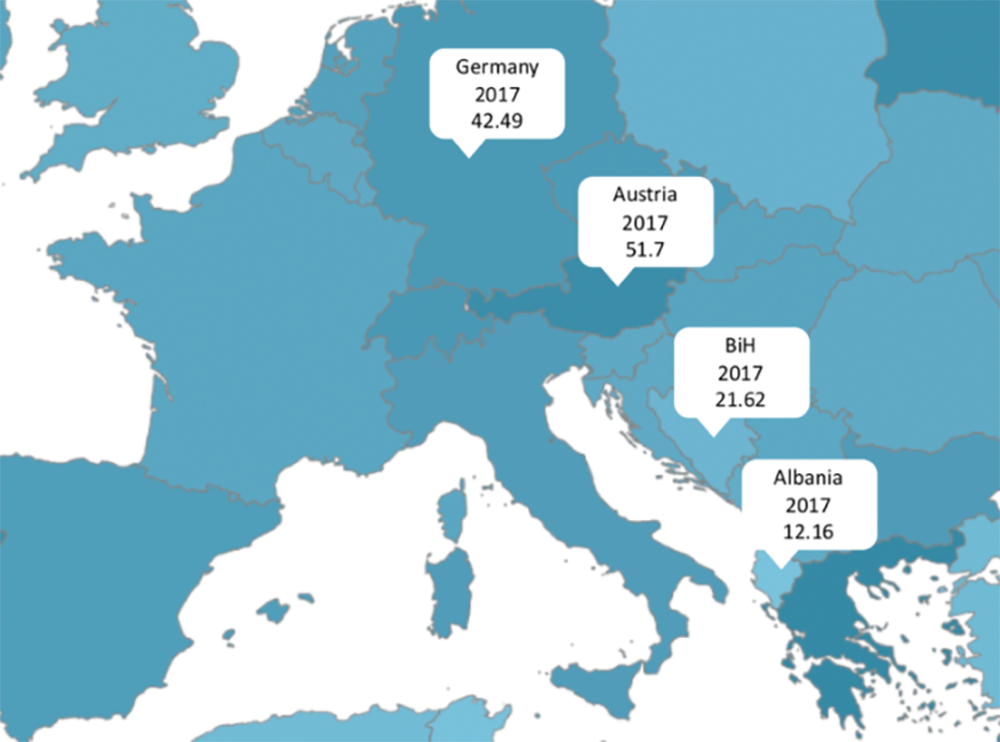

Density of medical doctors (total number per 10 000 population, latest available year)

During the months of March and April 2020, when it became clear that the pandemic was spreading at unprecedented speed, Austria chartered flights from the Bulgarian capital Sofia and the Romanian city of Timisoara to bring in medical staff from those countries, in order to ensure that full-time care in Austria remains uninterrupted. Putting it into the perspective, this becomes even more interesting. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2016, Austria had almost 52 doctors per 10,000 citizens, which is almost three to four times more than in Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina, who reported 12 and 21 respectively.

What next?

How much longer can the Western Balkans ignore the persistent problem of challenging demographics and high rates of emigration? The region has an ageing population, with 15 percent aged 65 and over; this figure is set to rise to 26 percent by the middle of the century. The Balkans’ demography is problematic given the number of elderly people in these countries who have been characterized as a vulnerable group in the pandemic. If the loss of competent citizens to foreign labour markets continues, it will impose economic, financial, and social costs that are very difficult to repair.

Further, with economic growth projected to be less than 3% prior to the pandemic, and in sharp decline with the new COVID -19 circumstances, no country in the region can effectively afford this level of emigration going forward.

To be able to respond to such challenges, Western Balkan regional governments must retain and leverage the talents of highly skilled citizens who have not emigrated. Making attractive programs and stimulating their personal growth is key to preventing human capital flight. While overdue, programs to slow emigration of skilled workers must be incorporated into the policies of each Western Balkan state government.

A way forward: Stimulating circular migration

While remittances remain an important source of financial support for the communities back home in the Western Balkans, to date this money has had a limited impact on promoting crucial changes in the region, particularly in the area of research and science. This is even more remarkable, given that the average level of education increased among migrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina as they migrated to a host country and that most continued their education in their respective host country. As it stands, circular migration is merely an unstructured process established and maintained by migrants themselves, whereby migrants maintain networks in both their countries of origin and emigration, while benefiting from these networks independent of any relationship or connection to the government of their country of origin.

The most commonly known regulated scheme of migration in the former Yugoslavia was a “guest worker” program in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, where Germany targeted low-skilled laborers for jobs in the industrial sector. More recently, efforts to regulate circular migration undertaken by the EU Commission had relative success. However, the 2008 economic crisis changed the course of these efforts.

Enabling milieu for diasporas

More than 80 million Europeans live abroad. Collectively, they would constitute the largest state within the EU. Further, the new reality is that emigration is far less permanent than it was in previous decades. The truth is that many who leave are not gone for good, but rather move in so-called contract migration – leaving their country for a limited number of years and later return. Virtual jobs and increasing growth of jobs available online contribute to a steady shift towards less permanent migrations. Temporary migrants in developed countries outnumber permanent migrants three to one, and between 20-50% of migrants leave their host country within 3-5 years.

By allowing portable benefits across countries, extra training, and specializations, but also making sure that the skills gained abroad are recognized and valued back home, governments can change the labour and emigration dynamics within a society profoundly. To move and work in different places has never been easier, especially in some sectors.

To offer a comprehensive framework for how circular migration might work and how it can be tailored to a specific setting is extremely important. This is even more important for smaller countries with higher rates of skilled emigration and fewer possibilities to quickly replace skilled workers.

The basic premise that a migrant should have the right to return to the host country and anchor herself or himself back home at any point is, at minimum, the foundation for circular migration. Rights that follow with such an arrangement must secure timely and full disclosure of information about the conditions, labour and pension rights, and the possibility for dual citizenship and permanent residence permits.

Circular migration policies must be realistic in order for them to be implemented. Profound and long-term changes in legislation, welfare support, circular migration services, open and accessible business networks, philanthropy, expansion of programs abroad, research on diaspora, diaspora conventions, experimenting with new social technologies and boosting Western Balkans’ associations and organizations abroad are just some of the measures to should be taken. By putting forward these measures, Western Balkan countries could quickly transform skills and know-how to tangible results. Setting up national global electronic databases to include all diaspora members and diaspora-related organizations would enable efficient knowledge and experience exchange between communities. The existing infrastructure in the region can play an important role alongside national governments.

In the case of the Western Balkans, each country should be working actively to create and implement circular migration policies with the countries where most of its emigrated citizens reside: Germany, Austria, Slovenia, the United States, and Canada. Serbia’s upcoming project, the establishment of an Agency for Circular Migration shows promise, not solely to gather experience in one place, but also to test the model of cooperation between citizens and governments, which is often characterized by shared mistrust between the two.

Emigration should be included as part of a comprehensive foreign policy dossier by governments and accordingly given the highest importance. Governments should mobilise their resources to connect with their diaspora and to map out the possibilities for collaboration. As it stands, knowledge about diaspora members, their networks, and skills is scattered and very uneven. Taking the lessons learned from experiences of other EU countries would be a move in the right direction for the Western Balkans. This is particularly true for sectorial and economic analysis of migration.

Finally, the key to success is identifying active individuals and organizations in the diaspora and connecting them with counterparts in their home country. A small contingent can make a significant difference, and one-to-one relationships are key. The resources gained at a very individual level can easily be scaled if there is some structural support present. There are very real advantages to bringing experienced people back, temporarily or permanently, to their home country. However, this approach also requires building support within the country for the diaspora with enough resources and with full support from the local government. In sum, given the current restrictive immigration policies and demographic challenges facing the region, circular migration may well be the most useful policy any country in the Western Balkans can employ.

Conclusion and recommendations

Undeniably, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the shortcomings of the public system that the Western Balkan countries have been ignoring for some time. High emigration rates of highly skilled people, specifically doctors, coupled with the health care sector’s limited capacity have pushed many countries to the edge and the crisis is far from over. Indeed, the pandemic intensified the region’s deep seated and long-term disregard of important issues and highlighted the importance of retaining skilled professionals in the country.

But it is precisely this kind of crisis that can turn policies around. If analysed critically, the COVID-19 crisis is an important opportunity for governments to rethink their strategies, to strengthen the existing public abilities, start investing into science and research, to reform and solidify healthcare systems in the region, and focus on retaining professionals at home, but also create and maintain connections with those who emigrated. One way to do this is through circular migration.

Temporary migrants in developed countries outnumber permanent migrants three to one, and between 20-50% of migrants leave their host country within 3-5 years. By allowing portable benefits across countries, extra training, and specializations, but also making sure that skills gained abroad are recognizable and valued back home, Western Balkan governments can change the labour and emigration dynamics within a society profoundly.

This scheme can help the Western Balkan countries quickly transform skills and know-how to visible results. Diaspora relations require that governments take on new thinking and new policies. Currently, apart from the remittances and sporadic, unregulated (non-institutional) connections, the Western Balkan diaspora is not part of any policy plans related to the future of their region of origin. To encourage the diaspora to become everyday actors in designing, modelling, and shaping the future of the region, there must be a conscious decision by policy makers to prioritize this issue.

While there are certain specificities in the countries throughout the Western Balkans, some general rules apply. The Western Balkans have enough suitable, well established platforms and initiatives that are able to absorb and embed diaspora activities. Establishing programmes targeting the return and circulation of migrants is one of the best mechanisms at policy makers’ disposal to use the existing skillsets and to improve service provision to the wider public.

The EU could greatly facilitate the participation of diaspora organizations by incorporating them into its bilateral relations with the government discussions on emigration policies. Afterall, Western European countries are politically and economically invested in the region, and it is of a mutual interest that the Western Balkans prosper.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of‘Europe’s Futures Ideas for Action’ project, the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) or ERSTE Foundation.

First published on 14 October 2020 at Europesfutures.eu. The article was produced within the framework of the Europe’s Futures project.

This text is protected by copyright: © Alida Vračić. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Bosnian nurse Majida Subai and her Spanish colleague in the Ageplesion Markus Hospital in Frankfurt am Main. Photo: © Andreas Arnold / dpa / picturedesk.com

Andreas Arnold / dpa / picturedesk.com