22 July 2020

Originally published

16 July 2020

Source

In Serbia, the Covid-19 pandemic only seems to exist if it benefits President Aleksandar Vučić. As a result, Serbia has seen the most serious protests in 20 years. This article reveals why this outcry is about more than just corona.

Anti-government protests are nothing new to Serbia. For years, frustration has been building over President Aleksandar Vučić, under whose rule the country is experiencing a democratic rollback. The protests of the past weeks, with thousands of people taking to the streets in several cities for days on end, however, marked a new phase.

Observers, including South-Eastern Europe expert Florian Bieber from the University of Graz, speak of the most serious police brutality since the overthrow of former Serbian strongman Slobodan Milošević twenty years ago. Videos of police officers beating civilians with batons were circulating on Twitter. “Public-service broadcasting should have reported on this,” says journalist Milica Vojinović, “but instead they ran a Jackie Chan karate film all night.”

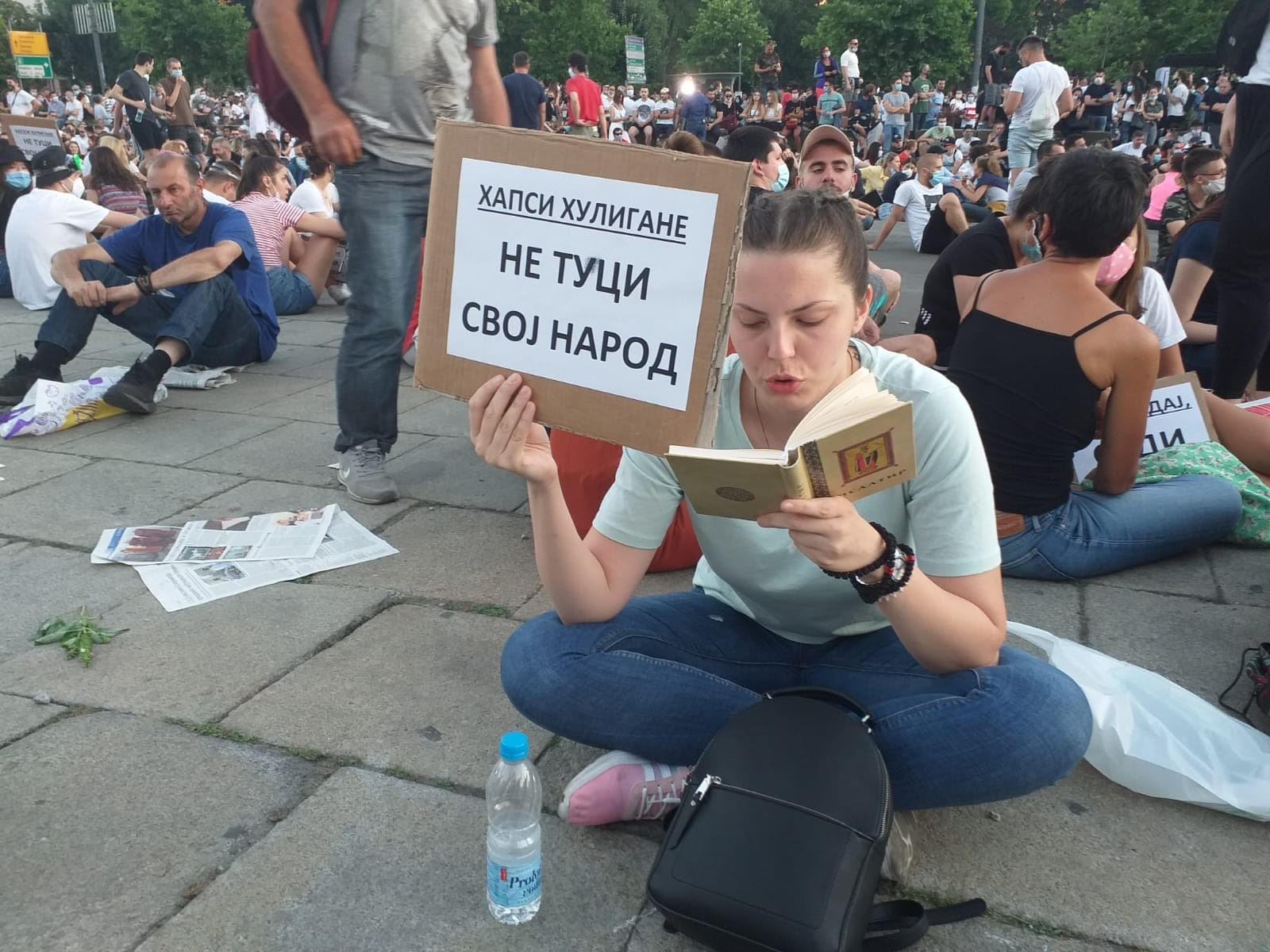

Serbian students protesting peacefully against the government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Photo: © Balkan Insight

Vojinović, 26, works for Krik, one of the last media outlets not controlled by the Serbian government or businesspeople close to the authorities. Two weeks ago, reporting from the streets of Belgrade, she saw protesters peacefully sitting cross-legged in front of the parliament, as well as hooded hooligans throwing stones and chanting nationalist songs. Then, on the third night, she got a cough and stayed at home for safety’s sake. Today she knows why her throat suddenly burned so badly. “There was just too much tear gas in the air.”

Fragmented and chaotic

A week later, important questions remain. Will the unrest threaten Vučić’s position? Who are the hooligans who deliberately mingled with the protesters? “Mere speculation,” says Milica Vojinović. But one thing is clear: The protests in Belgrade are about more than just measures to contain the spread of the coronavirus. For years, rage has accumulated over Vučić’s increasingly authoritarian rule. The president is being criticised for fudging the numbers of people infected with Covid-19 in order to push ahead with a 21 June election. With success – his national conservative Progressive Party (SNS) soared to its best result ever with over 60 percent of the vote.

Vučić, who has been president since 2017, rules Serbia in a Viktor Orbán-like fashion. He controls the media with the broadest reach, and investigative journalists such as Milica Vojinović are discredited by the government and the tabloid media. While some media publish critical investigations, these have not reached the majority society for a long time.

“We live in an autocratic regime where the government is no more than the shadow of a president who feels empowered to pull the strings everywhere in the state,” says Aleksandar Ðoković, spokesman of “Ne davimo Beograd” (“Let’s not drown Belgrade”), a citizens’ movement that has grown over the years. The recent protests are different from earlier ones, he says – they are spontaneous, unorganised, chaotic. The activist does not believe they have the potential for a change of power.

“We live in an autocratic regime where the government is no more than the shadow of a president who feels empowered to pull the strings everywhere in the state,”

Political scientist Vuk Velebit agrees. He predicts that the protests will peter out: “I don’t think anything big will change in Serbia overnight.” The groups that take to the streets are too fragmented and hate each other – leftist reformers, pro-Europeans, nationalists glorifying war, violent hooligans, ultra-orthodox priests. Some call for more democracy, others for the reconquest of Kosovo, which declared its independence in 2008. “The protests lack leadership, organisation and common goals,” says Velebit. Moreover, there are increasing signs that the violent hooligans are acting on behest of the government and the secret service to shed a negative light on the protests.

Virus on, virus off

The protests were triggered by a press conference on 7 July, during which Vučić announced a lockdown for the weekend. To understand the angry reaction, you have to look back a few months: The Serbian government treated Covid-19 like a light switch that can be turned on and off at will. In late February, a medical advisor to the president denounced it the “most ridiculous virus in the history of mankind”. In mid-March, the government introduced a state of emergency and imposed a curfew – with the military patrolling the empty streets. People aged 65 and older were not allowed to leave their homes at all.

No other European country has imposed such drastic measures as Serbia, says Milica Vojinović: “During the week, we were not allowed to leave our homes after six o’clock in the evening, and at weekends there was a total curfew, sometimes for up to four days,” says the journalist. A colleague who had reported on shortages in a hospital was arrested and interrogated, she says.

The authorities abruptly lifted the lockdown at the end of May, claiming they had defeated the coronavirus. During a match between Belgrade football clubs Partizan and Red Star, 25,000 fans crowded in the stadium, and discos and restaurants opened without enforcing any social distancing and mask rules. All this had a political purpose, says Vojinović: “Voters were intended to feel safe to go to the polls.” This was the reason, rather than an unwillingness to isolate themselves, that made the Serbs so angry. It seems that for the president, the virus only exists if it serves to keep him in power.

Original in German. First published on 16 July 2020 on woz.ch.

Translated into English by Barbara Maya.

This text is protected by copyright: © Franziska Tschinderle. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Serbian students protesting peacefully against the government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Photo: © Balkan Insight