Eastern European cities are greatly expanding their public transport networks. Yet bicycles can do little against the love of cars and cumbersome politics.

For the people of Prague, public transport means one thing: everyday life. According to Prague’s transport services authority, just under 60 per cent of all passenger journeys in the Czech capital are made by tram, underground, or bus. The metro alone spans some 60 kilometres beneath the streets of Prague. Those travelling to Wenceslas Square must take the green A line to Muzeum station. In the evening, after people get off work, the trains of the red C line, which ends at Letňany, a prefab housing district in the north of the city, are crammed.

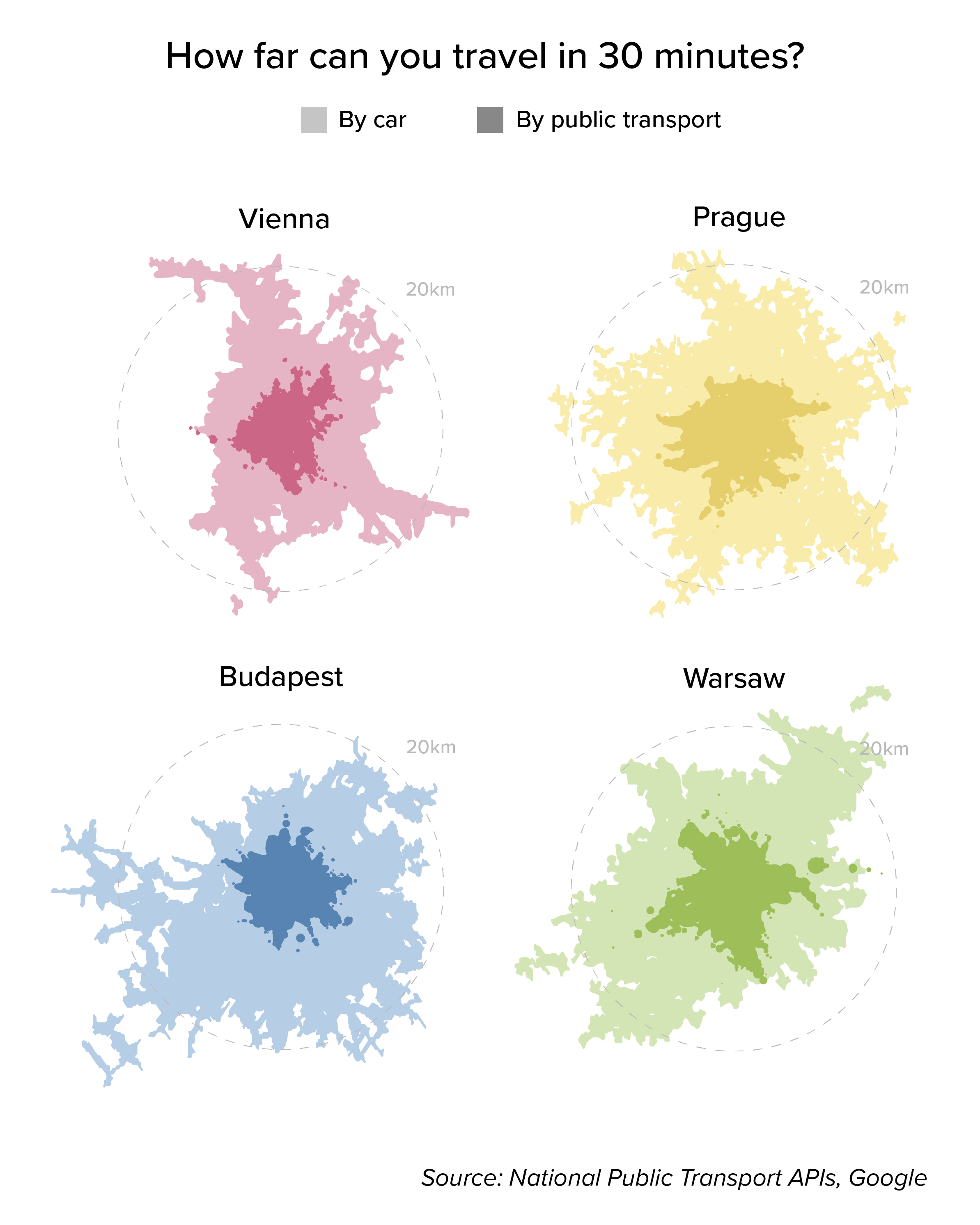

For comparison, in Vienna, a city praised worldwide for its public transport system, around 40 per cent of all journeys are made by public transport – primarily in the 80-kilometre-long underground network.

correspond to one per cent of Europe’s economic output and are lost each year throughout Europe due to traffic congestion.

100 billion euros

correspond to one per cent of Europe’s economic output and are lost each year throughout Europe due to traffic congestion.

The residents of Prague certainly appreciate public transport. It is considered cheap, efficient, and clean. And 86 per cent of them are satisfied with the city’s public transport system – a top ranking in Europe, for which the city is prepared to spend a fair bit of money. One third of its budget is allocated to the public transport system. Prague does not act out of self-interest: public transport has a decisive advantage, and not only in the Czech capital. Compared to private transport, metro systems make 20 times more efficient use of space than motorised individual transport, the concentration of which causes problems all over Europe. One hundred billion euros – which corresponds to one per cent of Europe’s economic output – are lost each year throughout Europe due to traffic congestion.

One approach to tackle environmental, noise, and space issues in European cities is to improve the public transport network. The alternative is to use bicycles. But the two concepts work best when combined. While Prague scores well with respect to the first approach, the results of the latter are poor. The city is incapable of meeting its own – relatively unambitious – objective of increasing journeys on two wheels to at least five per cent. Those residents of Prague who refuse to take a bike can’t be blamed. Cycle paths are poorly developed, there are too many cobblestone streets, and the fact that riding a bicycle is prohibited in the touristy inner-city areas around Charles Street, Town Hall, Charles Bridge, and the former Jewish ghetto is not helpful either. Especially when motorists still have the option of getting special permits for the pedestrian zone.

A least seven per cent of all journeys in the Czech Republic are made by bicycle. While the Central European country still lags behind the top performers in Scandinavia and the Netherlands, it does well when compared to other countries in the region. In neighbouring Poland, the figure drops to two per cent, and in Hungary it is at least 5.5 per cent.

Romania scores particularly badly with only 1.7 per cent. Those who have ever tried to escape Bucharest’s slow-moving, suffocating city traffic with their bicycles know very well why. Although the city added a bicycle lane to Calea Victoriei in 2015, a major thoroughfare leading to the historic centre, and is desperately trying to protect it against misparked cars, and although a lonely bike rental shop is trying its luck in the city ¬– Bucharest is relentlessly and self-destructively ruled by cars. Drivers lose about an hour a day in traffic jams, making Bucharest the only European city among the top ten most congested cities worldwide. At least that’s what the TomTom Traffic Index says, which the navigation specialist produces each year for 390 cities based on its own GPS database.

In Ljubljana, on the other hand, motorists only lose an average of 21 minutes a day. This is primarily due to the fact that the number of drivers in the Slovenian capital is decreasing. The percentage of people who use a bike for transport in the “European Green Capital” of 2016 might increase to 30 per cent within the next few years, which would be triple the current level. To achieve this, it must only continue to promote state-of-the-art traffic solutions with the same zeal as in the past. The municipality implemented its first bicycle paths in the 1970s. Today the city is a role model for the region with a network of 200 kilometres for 280,000 residents. The new Slovenska Street is at the heart of municipal efforts. The former four-lane traffic artery was transformed into an area for pedestrians, cyclists, and public transport in 2015.

While many people in Ljubljana have switched to bicycles, the rest of Slovenia lags behind. More than half of Slovenes own a car – which is similar to the situation in Austria. Several Western European countries have slipped below the 50 per cent threshold: Spain, Ireland, and Denmark, for example. Luxembourg has the highest number of car owners within the EU, while Romania ranks last, with only 220 cars per 1,000 inhabitants.

In light of this, it is particularly grim that Romania also has the highest number of road fatalities within the EU. In 2016 alone, 1,900 people were killed in almost 30,000 traffic accidents there. The primary reason for these accidents is the poor condition of public infrastructure – particularly outside the cities. The lack of traffic safety awareness (seat belts) and irresponsible road users also contribute to the high level of traffic accidents. In addition, the number of casualties on Romanian streets has risen lately, while it is dropping in most other parts of the EU.

Throughout the EU, an average of 50 people per one million inhabitants are killed in traffic accidents each year. With 54 fatalities, the Czech Republic is close to this average. Its capital Prague counted 23 road deaths in 2015, scoring relatively low compared to the EU average, but then absolute figures give a distorted picture because Prague has a population of “only” 1.3 million people.

Over the past 15 years, the municipality of Prague has been able to reduce individual traffic by almost 20 per cent thanks to its clever development of public transport – admittedly only in the inner-city districts. Traffic volume on the peripheral roads of Prague has increased by 50 per cent during the same period. With urban sprawl continuing at a fast pace, public infrastructure is no longer able to keep up, and new park-and-ride facilities only have an impact if steps are taken to develop rail transport and improve connections to regional transport networks.

At the other end of the spectrum, in Prague’s centrally located Karlín district on the banks of the Vltava River, the city has at least launched a city bike pilot project in 2016. Czech provider Homeport is considered a pioneer in bike-sharing solutions throughout Europe. Its first concept was implemented as early as 2009, but in La Rochelle, France, not the Czech Republic. It was a little embarrassing that the Czech company was unable to unveil a Czech project for many years, said Homeport founder Charles Butler in an interview with Radio Prague.

Original in German. Translated into English by Barbara Maya.

This text and infographics are published under the Creative Commons License: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. The name of the author/rights holder should be mentioned as followed. Author: Eva Konzett / erstestiftung.org, infographics & illustration: Vanja Ivancevic / erstestiftung.org.

Cover picture: Tram in the city center of Prague. Photo: © iStock/Tuayai.

Of People and Numbers – Eastern Europe in your pocket

Fourteen years have passed since the European Union set off towards the east. The initial euphoria first gave way to day-to-day life and has now turned into disillusionment on both sides. In some places people have become or remained strangers, despite visible and hidden relationships, and personal, official and business relationships. Despite the numerous similarities and the value chains that now know no borders. And sometimes precisely because of them.

Of People and Numbers aims to highlight the political, economic, cultural and social realities of life in the newer members of the EU and the accession states of South-Eastern Europe on a small scale and compare them to Western European realities, at least as they appear in Austria. Are the two really always miles apart? When does the view from above fall short?

When preconceptions are put aside, a different world emerges. Of People and Numbers brings this world to you in images, figures and words. A monthly serving of Eastern Europe. Delivered to your smartphone each month.