Freedom of the press is deteriorating in Europe. Excesses in Central and Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans are partly to blame.

In mid-October, the staff started to pack their things. They put laptops and documents, potted plants and personal belongings into boxes, labelling entire work histories for the move. Everyone was preparing to pick up their normal work routine in the new editorial office. Unbeknownst to them, though, there would not be any move. The boxes would never arrive at a new location. Instead, the daily newspaper Népszabadság would close and the journalists would lose their jobs.

When Népszabadság folded in 2016, Hungary lost its largest opposition newspaper. Shortly after, its then owner, Austrian investor Heinrich Pecina, sold the paper to Opimus Press, a holding company owned by the mayor of Felscút, along with a portfolio of 12 regional papers (a total of 19 regional papers are published in the country). Felscút is where Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán, was born. Lörinc Mészáros, the city’s mayor, is considered his friend. Mészáros is doing well from Orbán’s political rise, and today he is one of the richest men in the country. In the summer of 2017, another three Hungarian regional newspapers with a total circulation of approximately 100,000 copies changed ownership. Again, businessmen closely connected to Orbán’s Fidesz party were behind the deal. The organisation Reporters Without Borders (RSF) has said that buying these last three independent regional newspapers was a great success for the Orbán administration. Large parts of the Hungarian media landscape, including TV and radio, now toe the government’s line.

Contacts are on the up, freedom is on its way out

This is bad news. And there’s more: things are also not looking good for freedom of the media in other Central and Eastern European countries. The situation is even worse in the Western Balkans, where foreign media companies have largely withdrawn from the region. They have been replaced by media empires built by local businessmen who have good connections to the upper echelons of power. Politicians verbally attack journalists in public. In Serbia for example, journalists who are critical of the government are discredited as enemy spies.

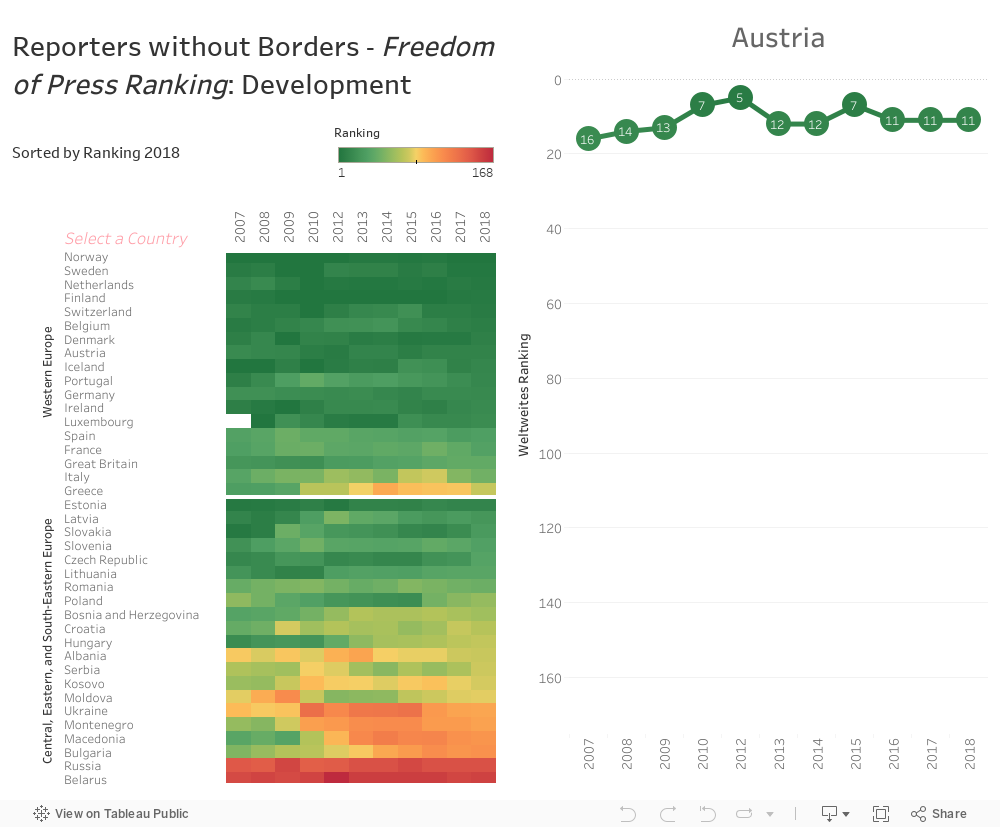

Indeed, the independent and international non-governmental organisation RSF says that the “traditionally safe environment for journalists” has begun to deteriorate all across Europe – and not just since the investigative journalists Daphne Caruana Galizia and Ján Kuciak were murdered in, respectively, Malta and Slovakia. According to the RSF’s 2018 annual report, press freedom deteriorated more in Europe than anywhere else in the world last year. RSF also cited the Austrian federal government’s harsh criticism of the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation (ORF) as a negative example.

Particular mention was, however, given to Slovakia: Freedom of expression is enshrined in the constitution, and defamation is a criminal offence punishable by up to eight years in prison. The prime minister, Robert Fico, who eventually resigned following the murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak, filed several libel charges against media companies. He had Václav Mika, the director of Slovakia’s public broadcaster RTVS, removed from office in the summer of 2017 and replaced with a pro-government manager. Slovak oligarchs have divided most of the private media between themselves.

Hungary and Montenegro have each dropped more than 50 places in the Press Freedom Index since 2007. Macedonia fell even further, dropping 73 places to 109.

50

Hungary and Montenegro have each dropped more than 50 places in the Press Freedom Index since 2007. Macedonia fell even further, dropping 73 places to 109.

In neighbouring Czech Republic, one of the country’s most influential media moguls, Andrej Babiš, walks the corridors of power – as the prime minister. In 2013, a company owned by Babiš bought the media group Mafra, which publishes the Czech Republic’s two most-read dailies: Mladá Fronta Dnes and Lidové Noviny. A little later, Radio Impuls, the most popular Czech private radio station was added to Babiš’s media empire. Technically, the press should monitor politicians, but here politicians are policing the press.

Bulgaria is bottom of the pile

It therefore comes as little surprise that the Czech Republic and Slovakia are among the countries that have fallen furthest down RSF’s annual ranking of media freedom around the world. The Czech Republic dropped 11 places to 34, while Slovakia fell from 17 to 27. Each year, the World Press Freedom Index compares the situation of journalists and media in 180 states and territories. Ranking eleventh, Austria is well ahead this year.

Bulgaria, however, is at a deplorable 111 in Europe. Physical attacks and death threats against journalists are common in the country – especially when the reporters investigate the mafia.

Poland is also exerting indirect pressure on the media. Michał Fabisiak, a journalist working for the public radio station Polskie Radio, for example, was fired for refusing to disclose his sources for a report criticising the ruling PiS party. Just eleven days later, Barbara Burdzy, a journalist at the public broadcaster TVP Info, suffered the same fate after reporting on the murky links between the Polish secret service and politicians. The Polish government has now stepped up its influence and taken control of public service broadcasting.

A socialist legacy

Attacks against journalists, whether physical or verbal, are not isolated cases but excesses of the increasingly hostile atmosphere that surrounds reporters and makes it more and more difficult for them to do their job.

The situation is also repelling readers. Or at least it is in Hungary, where only one in five people – seven per cent fewer than in 2016 – now rely on daily newspapers for their information. At 72 per cent, TV reaches far more people, but very often Hungarians use social media channels to find out what is happening in their country and elsewhere. In its current Digital Report, the Reuters Institute says that scepticism towards state media is traditionally high in Hungary because of the country’s socialist past. Back then, people did not trust the politburo-controlled state media.

The same is true for many Hungarians today.

Original in German. Translated into English by Barbara Maya.

This text and infographics are published under the Creative Commons License: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. The name of the author/rights holder should be mentioned as followed. Author: Eva Konzett / erstestiftung.org, infographics & illustration: Vanja Ivancevic / erstestiftung.org.

Cover picture: © simonkr/iStock.

Of People and Numbers – Eastern Europe in your pocket

Fourteen years have passed since the European Union set off towards the east. The initial euphoria first gave way to day-to-day life and has now turned into disillusionment on both sides. In some places people have become or remained strangers, despite visible and hidden relationships, and personal, official and business relationships. Despite the numerous similarities and the value chains that now know no borders. And sometimes precisely because of them.

Of People and Numbers aims to highlight the political, economic, cultural and social realities of life in the newer members of the EU and the accession states of South-Eastern Europe on a small scale and compare them to Western European realities, at least as they appear in Austria. Are the two really always miles apart? When does the view from above fall short?

When preconceptions are put aside, a different world emerges. Of People and Numbers brings this world to you in images, figures and words. A monthly serving of Eastern Europe. Delivered to your smartphone each month.