26 February 2020

Originally published

04 December 2019

Source

Shkumbin Ahmetxhekaj reveals the alarming impact of emigration on Kosovo’s health system — exacerbated by an unregulated private industry churning out medical staff for export to Germany.

In the end, it was the commute that clinched it. Blerim Berisha was a resident cardiologist at the University Clinical Centre of Kosovo in the capital, Pristina, where he worked days administering electrocardiograms and ultrasounds. After an eight-hour shift, he would jump in his jalopy and barrel down the M9 freeway to the town of Klina, 60 kilometres west of Pristina, where he lived with his wife, daughter and son. Not that he would see much of them. The only way to make ends meet was to work night shifts at a prison 30 kilometres away. Then home for a quick nap, and back to Pristina to do it all again. “Sometimes it felt like I’d never get any sleep at all,” he recalled. “And forget about having time for my family.”

These days, Berisha, 42, drives to work past half-timbered houses in the picturesque town of Pegnitz, near the German city of Nuremberg, where he works as a cardiologist at the town’s main hospital. He makes 10 times his old salary and enjoys visiting historical sites on weekends with his wife and children. Five years after packing up his stethoscope and moving to Germany, Berisha has no regrets. “The decision to come here was the hardest, but it was a must,” he said, sipping an apple juice at his home in Nuremberg. While it was the punishing hours and long drive that hurt the most, his diagnosis of Kosovo’s ailing health system also swayed his thinking. “Corruption, narrow horizons and nepotism in state-funded institutions are killing the future of the country,” he said.

Blerim Syla, head of the Health Workers Union, is worried about the effects of medical brain drain. Photo: © Shkumbin Ahmetxhekaj

Berisha is one of hundreds of Kosovo doctors who have traded low pay and high stress for more rewarding lives abroad. Most go to Germany, which recognises Kosovo medical qualifications. As the pathway to migration gets ever easier for Kosovo’s doctors, nurses and other health workers, BIRN can reveal the full extent of medical brain drain in Europe’s youngest state. In a country with one of the lowest densities of physicians on the continent, a doctor emigrates every other day while two nurses leave daily, figures from the Chamber of Doctors and Chamber of Nurses show, respectively.

Croatia’s Medical “Minefield”

Kosovo is not the only place in Southeast Europe facing medical brain drain. The phenomenon affects countries across the region, including the EU’s newest member, Croatia. The Croatian Chamber of Physicians says more than 10 per cent of Croatian doctors — around 1,700 — have requested the certificates needed to find work abroad. “I usually say that the Croatian healthcare system is a minefield for doctors and patients, with the situation deteriorating every day,” said Ljiljana Ćenan, a family doctor in the eastern village of Ivankovo. After 20 years working in the village, Ćenan has secured a job in Sweden. She says it will be hard to find a replacement when she leaves.

Like their counterparts in Kosovo, many Croatian doctors complain of limited opportunities for specialist training. In a bid to stop the exodus, Croatia requires doctors on residency programmes to keep working at host hospitals once they finish their residencies — or pay a fine of up to 135,000 euros.

Ivan Bekavac, head of the Chamber’s Office for Medical and International Affairs, said while he opposed shackling young doctors in this way, the country faces a serious problem. He cited the example of a hospital in Slavonski Brod that announced a vacancy for 32 doctors but only got seven applications. “Our new [online] system shows how many doctors in the next few years will retire in every county, and how many doctors according to every specialisation have their papers ready to move abroad,” he said. Croatia has around 470 retired doctors who continue to work part-time due to a lack of new physicians.

The emigration comes at a cost: wards depleted of staff, patients left in limbo, institutional knowledge squandered. Then there is the price tag for taxpayers — around 100,000 euros to train each new doctor. “The storm is on the way,” said Afrim Blyta, a professor of neuropsychiatry at the Faculty of Medicine at Pristina University. “I can say that 95 per cent of students are learning German and aiming to go to Germany. Soon Kosovo will face acute shortages in the healthcare system.” Health experts blame the crisis on low wages and dismal job prospects in Kosovo coupled with voracious demand for medical staff in Germany as Europe’s biggest economy grapples with an ageing society.

But a lesser known phenomenon also drives the stampede: a thriving private industry whose sole purpose is to churn out ready-made health workers to send to Germany. From conveyor-belt colleges and hungry headhunters to a booming trade in fake qualifications, BIRN lifts the lid on this largely unregulated export-a-medic market. Critics say its effect is to leech the country of talent while promoting quantity over quality, with serious consequences for public health.

Doctors without borders

In Gorancë, a village nestled in the hills of southern Kosovo, locals are used to their doctors upping sticks to Germany. The last one left several months ago, and few hold their breath for a replacement. At the medical centre, nurse Sevime Shkreta does what she can to tend to the sick and injured. She is handy with a thermometer and ties a mean bandage. But often she has to send patients to the municipal health centre in Hani i Elezit/Elez Han to the east.

That is not an option for the family of 65-year-old Arife Berisha (no relation to Blerim Berisha). She suffers from hypertension while her husband has heart issues and her mother-in-law has diabetes. “We can’t afford to travel to Hani i Elezit because we have no car and my sons are unemployed,” she said as nurse Shkreta took her blood pressure.

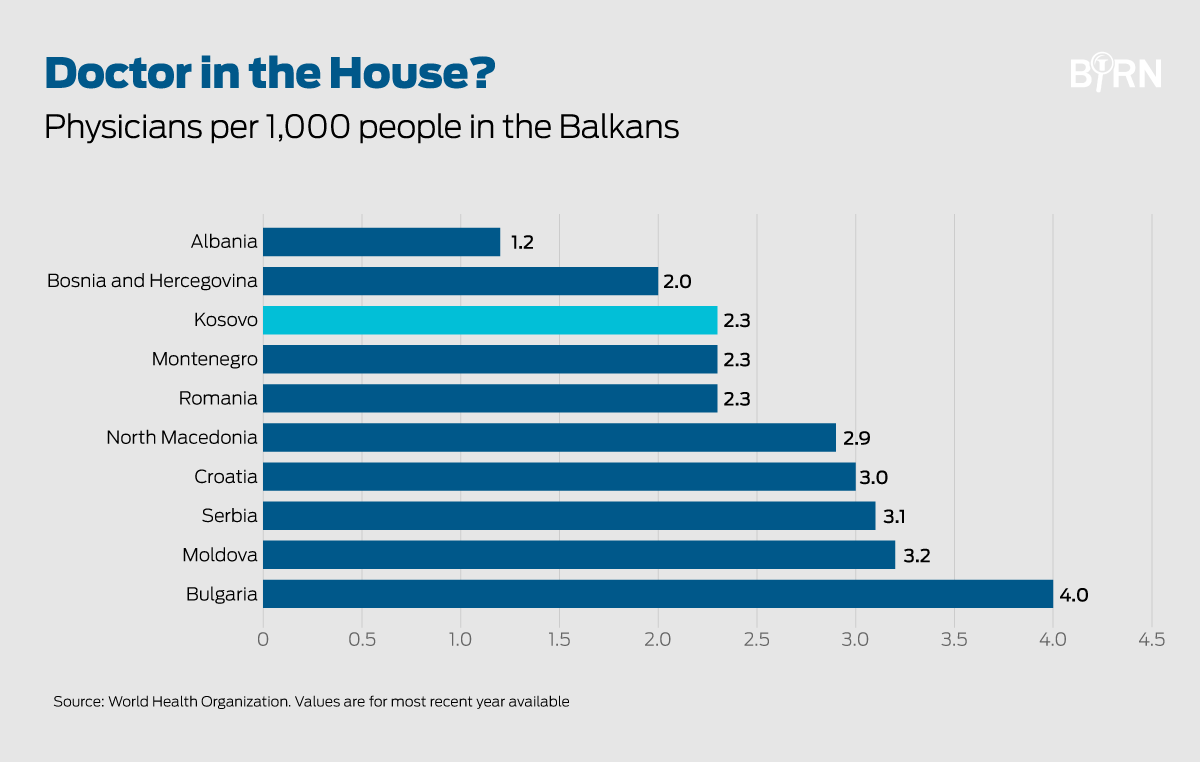

All over the country of 1.8 million, once-bustling medical centres have turned to ghost clinics. Even regional hospitals in the western cities of Pejë/Peć and Gjakovë/Ðakovica have had to close some units. Nationwide, 4,100 physicians practice their craft, according to the Chamber of Doctors. That is 2.3 doctors per 1,000 people, one of the lowest ratios in the 47 countries that make up the Council of Europe. The only nations with worse ratios are Albania (1.2), Turkey (1.8) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (2.0), according to World Health Organisation data. In contrast, Germany has 4.2 doctors per 1,000 people and Sweden has 5.4.

Pleurat Sejdiu, head of the Kosovo Chamber of Doctors, says the country needs at least 5,000 physicians to meet standards recommended by the World Health Organisation. That leaves it 900 short at current levels. Meanwhile, statistics show alarming levels of attrition. For every 150 new doctors graduating each year, at least 180 physicians leave the country, Sejdiu said. “Most of them are planning to leave Kosovo, despite the fact that they will have to go through additional training and practice in the host country,” Sejdiu said. Over the past year, he received 176 requests from doctors for certificates of good standing that are legally required to seek employment abroad.

Suzana Manxhuka Kerliu, dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Pristina, is also inundated with requests for certificates from former and current students looking to emigrate. “The negative part is that our brain power is leaving,” she said. “On the plus side, what we’re offering to the market is being assessed positively, but for us it’s going to be bad because we’re going to face shortages.” She added that almost all medical students at the University of Pristina attend private language colleges to learn German, in preparation for job-hunting. “You can’t ask someone to stay put out of patriotism,” she said. “Not if we don’t offer the right conditions for them to work and study.”

“You can’t ask someone to stay put out of patriotism. Not if we don’t offer the right conditions for them to work and study.”

The irony is that despite the doctor deficit, many medical graduates struggle to find work in Kosovo. The Chamber of Doctors says Kosovo has produced 440 qualified physicians who have not found jobs — at least not on home soil. Experts blame a culture of nepotism in a country that spends only 220 million euros a year on public health, according to the health ministry. That is 122 euros per person, compared with around 5,000 euros in Germany. “If you don’t have connections, it’s hard to get a job or a place on a residency programme,” said Blerim Syla, chairman of the Federation of Health Unions of Kosovo. But even those who do get contracts have itchy feet. A recent survey by the Chamber of Doctors found the top reason for medical staff seeking greener pastures is poor working conditions, followed by a lack of opportunities for professional development. Only then did low salaries factor.

Nursing students at the University for Business and Technology in Pristina attend class. Many aim to leave for Germany. Photo: © Shkumbin Ahmetxhekaj

Flamur Llabjani, 34, is a typical malcontent. The aspiring gastroenterologist graduated five years ago and is near the end of a residency programme at the University Clinical Centre of Kosovo in Pristina, where he works 18-hour days, commuting from the city of Ferizaj/Uroševac, 40 kilometres to the south. “Unfortunately, the older doctors who are supposed to teach us and transfer their knowledge aren’t doing it, with one exception,” he said. Llabjani fears he will finish his residency without learning how to perform basic diagnostic procedures such as gastroscopies and colonoscopies. He believes he would be further stretched in Germany. “I used to be strongly against people leaving,” he said. “Now I see that even my close friends who begged me not to leave are considering it.”

Business is booming

Germany needs another 70,000 doctors and nurses on top of the 500,000 it already employs, the German health ministry says. Around a tenth of the workforce comes from abroad, drawn to a country that spends more on public health than any other in Europe — 351.7 billion euros in 2016, according to the EU’s statistics agency, Eurostat. Only a fraction of foreign doctors in Germany are from Kosovo. The German Chamber of Physicians puts the number at 292, though Kosovo’s Chamber of Doctors says it is in excess of 450. Tiny as those figures are compared with Germany’s population of 84 million, they represent a sizeable slice of Kosovo’s medical workforce. And experts say the floodgates in Kosovo are opening — especially when it comes to nurses.

“It’s impossible to properly educate more than 4,000 students. I see them walking every day through the halls of clinics, but they don’t get the right practice.”

Kosovo has around 27,000 certified nurses, according to the Chamber of Nurses, though only 21,000 are employed in the country. Chances are, most of the remaining 6,000 work in Germany. Many more are on the way. In 2016, Kosovo allowed private colleges to start training nurses and midwives en masse. Six now do so, alongside two public universities that offer studies in medicine. While private colleges can churn out graduates without limit, public universities are bound by a cap of 50 students per year for each institution, as set by the Kosovo Accreditation Agency (KAA), which oversees higher education standards.

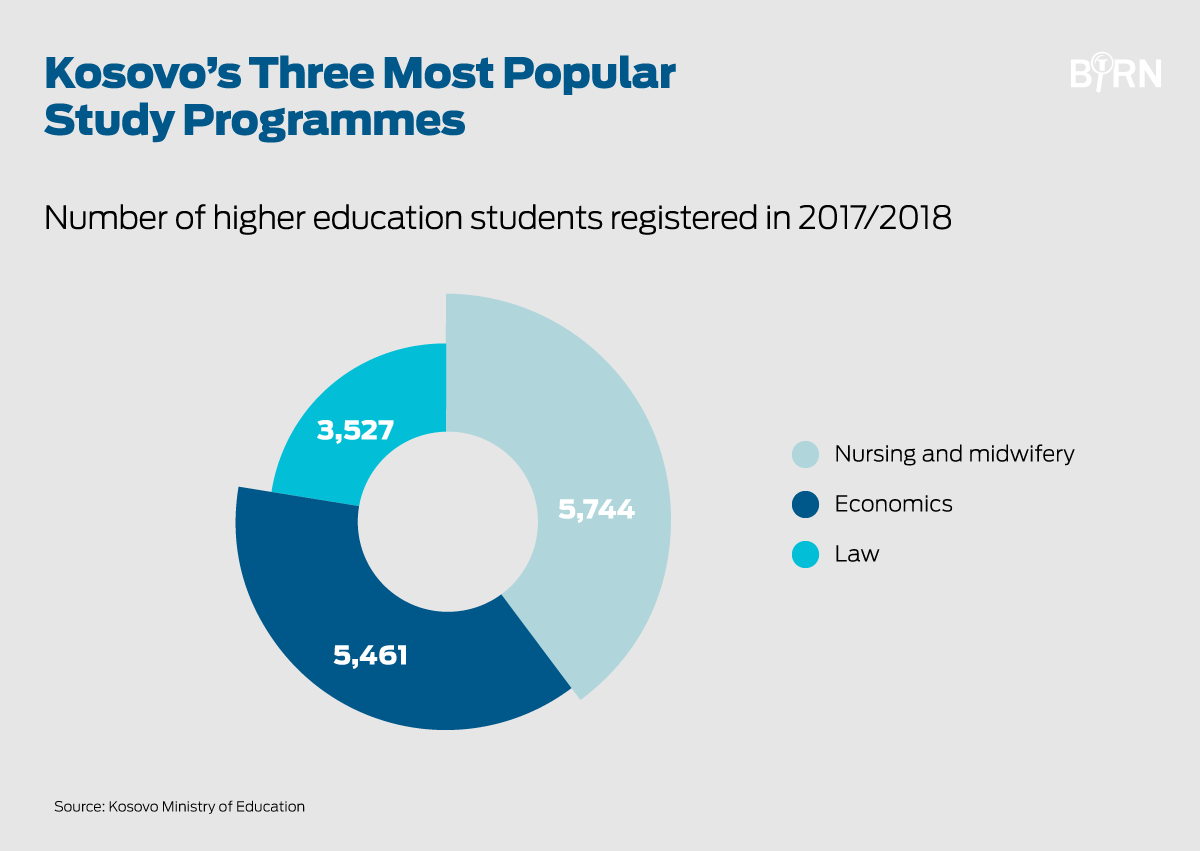

The entry of the private colleges onto the scene resulted in an explosion of enrolments in nursing. Before long, the discipline leapfrogged economics and law as the country’s most popular choice of study. More than 5,700 students were admitted to study nursing and midwifery in the 2017/18 academic year, the education ministry said. The first generation of private college students will graduate this year — thousands of new nurses looking for jobs. Critics say the surge in nursing admissions raises questions about quality control (see box: A Question of Standards). “It’s impossible to properly educate more than 4,000 students,” the Chamber of Doctor’s Sejdiu said. “I see them walking every day through the halls of clinics, but they don’t get the right practice.”

Emigration ecosystem

It is no coincidence that an entire ecosystem has sprung up to deliver health workers to the German market. Hundreds of language centres across Kosovo promise to help wannabe emigres pass the German language tests required to apply for a working visa. Most private colleges have contracts with headhunting agencies set up to find staff for hospitals in Germany. Michael Weiss-Gehring, manager of the nursing department at the Hassberg Clinic public hospital in the Bavarian town of Hassfurt, told BIRN that German hospitals typically pay around 6,000 euros to headhunters for every doctor or nurse placed.

A Question of Standards

As thousands of students turn to nursing as a way to move to Germany, health experts worry about standards slipping. Suzana Manxhuka Kerliu, dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Pristina, condemned a decision three years ago by the Kosovo Accreditation Agency (KAA) to allow private colleges to admit unlimited numbers of nursing students each year. “How can our faculty only be allowed to admit 50 students in nursing while private ones can admit thousands?” she said. “‘It’s good to have competition, but we should pay attention to quality and rigid monitoring.” KAA head Gazmend Luboteni said the decision was based on an assessment that “the needs of the market were higher than what the Faculty of Medicine was offering” — despite the fact that hundreds of medical graduates have not found jobs in Kosovo.

Lul Raka, a professor of microbiology at Pristina University and a former KAA board member, said Kosovo has breached both European Commission directives and its own laws on higher education. “Based on EU directives, titles such as doctor, dentist, pharmacist, nurse or physiotherapist can only be issued by a university or universities that are related to scientific institutions,” he said. “None of the private colleges fulfill this condition.” Adding to anxiety about standards are reports that some private colleges are cutting corners. “They don’t follow regulations … There are many staff with the title of professor who do not have PhDs,” Manxhuka-Kerliu said.

Private colleges, which typically charge students 1,000-2,000 euros a year, counter that the University of Pristina does not have a monopoly on quality. Fitim Alidemaj, head of the department of nursing at the private University of Business and Technology, said his institution invests more in staff and infrastructure. “We have 102 staff for nursing alone,” he said. Analysis by BIRN of staff resumes posted online reveals that all public universities and private colleges offering nursing have academic staff without the PhDs required by law. In many cases, lecturers are Masters students. In their defence, tertiary institutions cite an administrative order issued by the education ministry in 2017 giving them a five-year “grace period” to ensure staff have the necessary postgraduate degrees. The KAA is supposed to monitor universities and colleges to make sure staff are up to scratch, but some experts question its ability — or willingness — to do so.

In September, the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA), a Brussels-based umbrella group for quality assurance organisations, cancelled the KAA’s membership on the grounds it was not doing enough to safeguard standards. “There has been no monitoring or follow up of recommendations of earlier reviews,” the ENQA wrote in a letter to KAA, available online. “Monitoring has been limited to formal requirements only, limited to control rather than quality enhancement.” Experts say the ENQA’s move could make it harder for Kosovo students to have their qualifications recognised.

One of Kosovo’s biggest language centres is Pristina-based InterPersonnel, which offers 18 months of free German courses and nursing practice to around 550 students each year — all bound for Germany. The school makes its money purely from recruitment fees. Students must sign a contract agreeing that they will find a job through InterPersonnel, which works with German headhunting firm Dekra. “For every 140 free places, we get around 3,000 applications,” InterPersonnel executive director Musa Ahmeti said. “We’re not contributing to emptying Kosovo but reducing unemployment and offering nurses a chance for a better life.”

Sniffing an opportunity, headhunting agencies focused on Kosovo and other Balkan countries are popping up across Germany. “Demand from hospitals is high, and it’s increasing a lot,” said Sadik Shkreli, who left Kosovo in 1991 and now runs a recruitment firm in the town of Landshut, near Munich. He estimates he places 50-60 nurses a year from Kosovo, Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia.

But headhunters may soon find their services less in demand. In January, Germany will ease restrictions on foreign professionals seeking employment, allowing doctors and nurses to enter on six-month visas so they can look for work themselves. Jobseekers will still require proof of language proficiency — a significant obstacle for the less linguistically inclined. But some have found an easy, if unethical, shortcut.

BIRN interviewed four Kosovo emigres who claim to have paid others to sit language exams in their place. One was a 39-year-old nurse from eastern Kosovo, who decided to move to Germany after his mother died of breast cancer. A supply-chain problem at her hospital meant he had to pay for her medicines out of his own pocket, leaving him almost broke.

“Imagine what it’s like if you only make 400 euros a month and you have to buy medicine that costs 5,000 euros,” he said. “I felt abandoned. I was a medical professional myself, and I couldn’t give much more help to my mother.” To get a visa appointment at the embassy, the nurse needed a certificate showing B2-level fluency in German. He said he found himself agreeing with British playwright Oscar Wilde that “life is too short to learn German”. For 2,000 euros, he did not have to.

Examiners such as the Austrian German Language Diploma (OSD) and Goethe Institute say they are doing all they can to prevent such deception. “Exam providers like OSD are being massively damaged by the depicted fraud in connection with the obtainment of language exams,” Brigitte Mitteregger, head of the Vienna office of OSD, said in an email. Reports of cheating have prompted the German Embassy in Pristina to limit its list of exam providers whose certificates are admissible to OSD and Goethe-Zentrum in Kosovo; OSD in North Macedonia and Austria; and the Goethe Institute and TELC in Germany.

New horizons

In February 2019, Kosovo’s parliament approved a new law on salaries that will almost double doctors’ pay, though it has yet to be implemented. Doctors at public hospitals now make between 600 and 750 euros a month. Nurses will also see an increase of about 50 per cent to around 600 euros a month from 400 euros a month.

“Along with an improvement in working conditions, young doctors and nurses should think twice before leaving,” said Basri Sejdiu, director of the University Clinical Centre of Kosovo. He added that the centre, which manages regional hospitals, is working on overhauling residency programmes across the country so work placements are allocated fairly.

The health ministry seeks to boost the number of medical students at the University of Pristina to up to 250, from the current 150. At the same time, Gazmend Luboteni, head of the KAA academic standards watchdog, said he plans to reintroduce quotas on student admissions at private colleges, starting from this year.

Such attempts to retain talent may be offset, however, by an agreement signed by Kosovo and Germany in July to open a regional centre to train and accredit nurses from Kosovo specifically for the German market. The centre, to be set up at a location in Kosovo yet to be decided, will offer state-funded training, practical work experience and German classes for aspiring nurses. In return, Germany will help Kosovo strengthen its health system, including developing public health insurance.

Hospital managers say integration of foreign staff can be a problem too. “Even after we hire staff, it may take two years to have full integration of a new employee here,” said Michael Weiss-Gehring, a nursing manager at the Hassberg Clinic in the German city of Hassfurt, where half of all doctors are non-German. Weiss-Gehring organises weekly gatherings over beer to help staff improve their language skills and better integrate. “The language is the biggest problem that we have, but the other thing is culture,” he said. “People come from completely different health systems — especially for nurses, because the work they do here is completely different.” He added: “Many patients believe that doctors don’t understand their problems.”

Alfred Schmitt, an 82-year-old patient at the Hassberg Clinic, said it did not bother him that many staff were non-German. “They understand my needs,” he said. But an Albanian nurse working in the southern city of Munich said others were less tolerant. “In one of the night shifts, out of 10 staff, only two were Germans,” said the nurse, declining to be identified. “You could hear patients complaining and cursing about the fact that they were being treated by foreigners.”

Critics fear the initiative could become a conveyor belt for those seeking a one-way ticket out of Kosovo. Asked by BIRN at a news conference if the government was trying to promote medical emigration, Health Minister Uran Ismaili said: “It’s in their right to decide if they want to return or not.”

Meanwhile, Kosovo health workers may find their choices multiplying as other countries open their doors too. InterPersonell executive director Ahmeti said his company is in talks with the Swiss Red Cross, which certifies nurses, to “open a new market in Switzerland”. “Salaries are extremely good, and they start at 8,000 Swiss francs (7,200 euros) [a month],” he said. “But they’ll need to have at least three years of work experience and have B2 level of German.”

For doctors like Blerim Berisha in Pegnitz near Nuremberg, it is not all about money. Asked what, if anything, could lure him back to Kosovo, he thought for a moment before replying. “Respect and integrity,” he said.

First published on 4 December 2019 on Balkaninsight.com.

This text is protected by copyright: © Shkumbin Ahmetxhekaj, edited by Timothy Large. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Arife Berisha, 65, has her blood pressure taken by a nurse in the Kosovo village of Gorancë. Photo: © Shkumbin Ahmetxhekaj

This article was produced as part of the Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.