The Kyiv Biennial was established by the Visual Culture Research Center (VCRC) amid turbulent political changes in 2015. While the Maidan revolution gave impetus to important political, social, and cultural changes in Ukraine, these were overshadowed by Russia’s occupation of Crimea and the beginning of the war in the Donbas region.

We sat down with Vasyl Cherepanyn, head of the VCRC for an online discussion to talk about the unwalked path the Kyiv Biennial followed since then. We touched upon topics such as the legacy and influence of the Maidan revolution(s) on the Ukrainian cultural and artistic field, the specificities of being an artist or a cultural practitioner in Ukraine, the future perspectives of the European cultural field, and how East Europe can earn a new subjectivity for itself.

Vasyl CherepanynVasyl Cherepanyn (Ukraine, 1980) is head of the Visual Culture Research Center (VCRC), an institution he cofounded in Kyiv in 2008 as a platform for collaboration among academic, artistic, and activist communities. He holds a PhD in philosophy (aesthetics) and has lectured at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder), University of Helsinki, Free University of Berlin, Merz Akademie in Stuttgart, University of Vienna, Institute for Advanced Studies of the Political Critique in Warsaw, and University of Greifswald. He was a visiting fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna in 2016. He coedited the Guidebook of the Kyiv International (Medusa Books, 2018) and ’68 NOW (Archive Books, 2019), and curated The European International (Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten, Amsterdam, 2018,) Hybrid Peace (Stroom, The Hague, 2019), and Armed Democracy (2nd edition of Biennale Warszawa, 2022), among others. is the cofounder of the VCRCVCRC is the organizer of the Kyiv Biennial (The School of Kyiv, 2015; The Kyiv International, 2017; The Kyiv International – ’68 NOW, 2018; Black Cloud, 2019; Allied, 2021, and a founding member of the East Europe Biennial Alliance. VCRC received the European Cultural Foundation Princess Margriet Award for Culture 2015 and a grant of the Igor Zabel Award for Culture and Theory in 2018., established in 2008 in Kyiv as a platform for cooperation between scientific, artistic and activist communities. Since 2015, the VCRC organizes the Kyiv Biennial, an international forum for art, knowledge and politics that adopts an interdisciplinary perspective integrating exhibitions and discussion platforms. The Kyiv Biennial is a founding member of the East Europe Biennial Alliance, a group including Biennale Warszawa, Biennale Matter of Art Prague, OFF-Biennale Budapest and Survival Kit Festival Riga.

From an outsider’s point of view, it is not easy to understand the complexity of the circumstances in which the Ukrainian cultural and artistic field tries to operate at the moment. In order to get a better understanding, I think it would be worth going back in time and having a proper look at the path the cultural field as well as the Kyiv Biennial have walked through in the last few years. I suggest revisiting Maidan which seems to be a starting point for me. Looking back now, what does it mean to you?

Maidan is indeed a basic starting point in many senses. In the history of Ukraine, various unrests and uprisings took place on the central Independence Square, or the Maidan of Independence in Ukrainian. It is a kind of traditional spot for that matter. The one in 2014 can be perhaps called the last European revolution so far. Besides its local meaning, it had a pan-European importance and was part of the global wave of uprisings starting with the US Occupy Wall Street and including the so-called Arab Spring.

In the Eastern European context, where right-wing populism and different authoritarian tendencies had been dominating the political stage, Maidan demonstrated a unique example of opposition to all that. I would say, the Ukrainian society as we know it now was born on Maidan. It had importance in showing an opportunity of the protest that made other protests possible. In this sense, it was a founding act that enabled the activation of the civil society and social field as such. Not just the Kyiv Biennial, but any kind of cultural involvement in the societal realm would not make sense without Maidan. It also meant a founding act for political life as it marked the beginning of a different approach to the state from the point of view of Ukrainian society itself.

We can call Maidan a Gesamtkunstwerk. It was functioning as a total installation with different aesthetical, political, social, and economic dimensions being constantly medialized during its development. Beyond this, most importantly Maidan has won as a political phenomenon. It’s demonstrated a crucial thing for East European region: that revolutions do work and they do improve the state.

Vasyl Cherepanyn at Maidan. Photo: Diana Iwanowa

Maidan embraced people throughout the whole territory of Ukraine and has shown the extent to which its citizens can get self-organized. On 24 February 2022, after the initial shock, the Ukrainian society managed to regroup itself again and resist on an unbelievable scale. The whole country has turned into a collective armed Maidan, but this time, together with the state.

The first edition of the Kyiv Biennial, The School of Kyiv, was strongly built on the experiences of the revolution attempting to draw conclusions from the Maidan movement and investigate what Ukraine and Europe could learn from each other. When you launched the Biennial, what was the Maidan legacy that you wanted to channel into your activities?

The Kyiv Biennial was based on the idea of square occupation, not only in a political but also in a cultural sense. We wanted to continue the same intention that emerged on Maidan: to transform the public cultural realm into a political agora, on which cultural practitioners, artists, and academics could further their ideas. Moreover, preparing such conditions, which would be fruitful for the incorporation of those initiatives and public political spirit that were present on the square. In a certain way, the Biennial was a sort of continuation of Maidan in the cultural field in order to deliver its promises. As an umbrella project gathering various artistic initiatives and discussion platforms, the Biennial can be regarded as another type of Gesamtkunstwerk. In the first edition, it was projected on Kyiv, the city of Maidan, in order to create an institutional framework for the follow-up of this work.

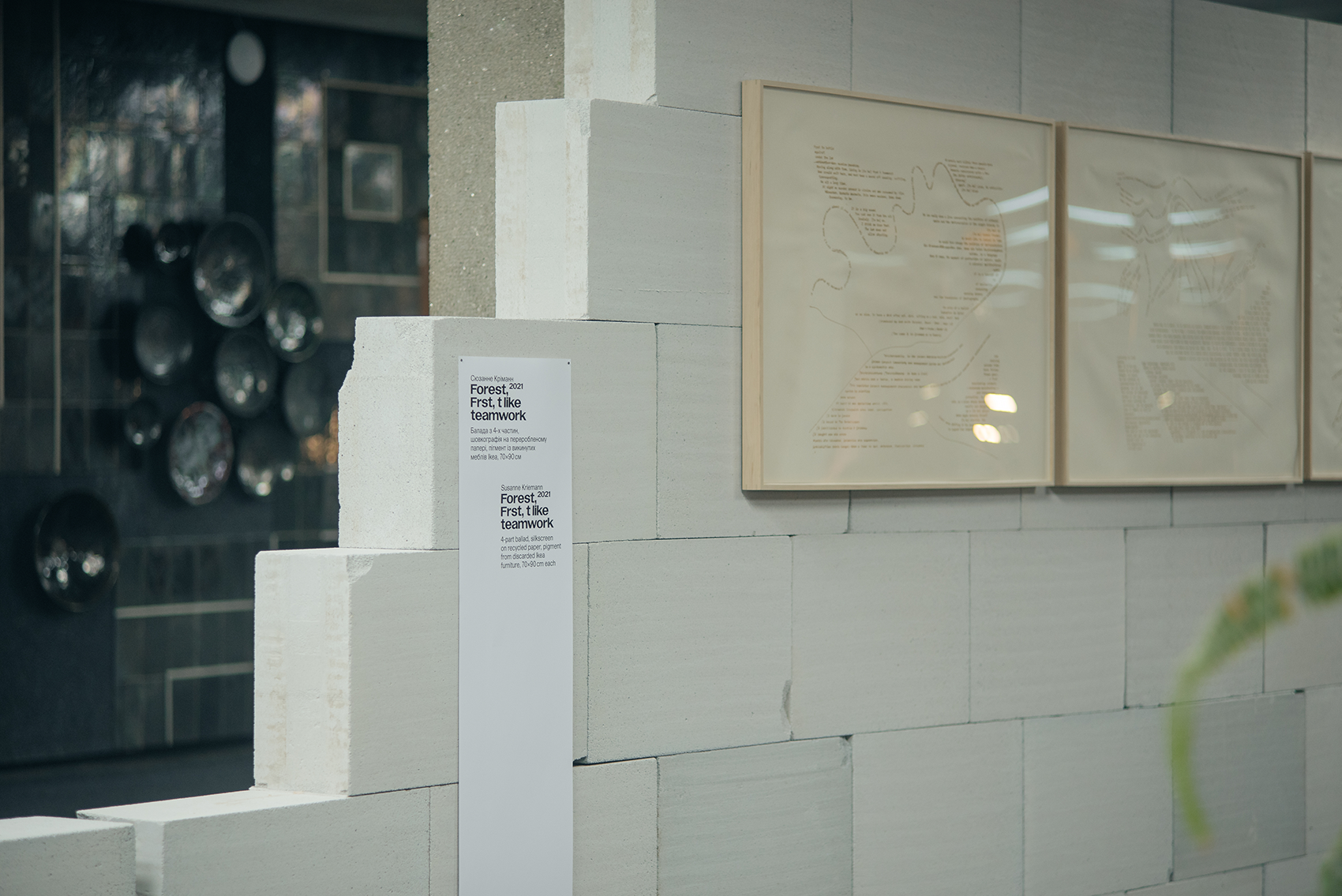

Allied – Kyiv Biennial 2021. The House of Cinema, 16 October – 14 November 2021. Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

Allied – Kyiv Biennial 2021. The House of Cinema, 16 October – 14 November 2021. Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

How did Maidan influence the Ukrainian cultural and artistic field?

In Ukraine, the cultural field was formed by revolutionary events such as two Maidans in 2004 and 2014. The artistic scene that we currently know was born from the spirit of revolution. It had a great impact on how artists work, how they organize themselves, what media they use, which topicalities they investigate. The modus operandi of the cultural field was the result of an experience of being both an artist or a cultural worker and a citizen on the square. I think this is really unique. You can hardly find any other country in Europe, where culture is so much rooted and dependent on the nature of political upheavals and uprisings. If you want to analyse and understand contemporary visual culture of Ukraine, you have to take it into account; this revolutionary background is indeed a starting point. Ukrainian art institutions and artists themselves have developed many instruments that can be taken from here to elsewhere, like how and where they organize exhibitions, performativity, actionist practices, utopian thinking, documentality, use of public space. It was not by occasion, that the first edition of the Kyiv Biennial was entitled The School of Kyiv. Our intention was to establish a framework from which others can learn.

Allied – Kyiv Biennial 2021. The House of Cinema, 16 October – 14 November 2021. Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

Allied – Kyiv Biennial 2021. The House of Cinema, 16 October – 14 November 2021. Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

Transperiphery Movement – Global Eastern Europe and Global South. Curated by Eszter Szakács and Zoltán Ginelli. Allied – Kyiv Biennial 2021. The House of Cinema, 16 October – 14 November 2021 Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

I think you touched upon an essential point when you highlighted the impact of revolutions on the artistic field. I also agree that unlike in most European countries, it seems as if art can have a real political impact in Ukraine. However, I was wondering about the role of the context here. In my experience, this really sensitive and sophisticated visual language that artists use to mirror the anxiety and socio-political conflicts in Ukrainian society loses its power when works are exhibited elsewhere.

In a certain way, of course, it is contextually rooted. However, I think the nature of the Ukrainian cultural realm enables you to be active outside your professional field. In the West, you can do everything in art as long as you don’t intervene in politics. In Ukraine, the cultural and artistic field itself functions as agora. It is exactly the cultural field that has the potential of debating societal issues, provoking ideological questions or political polar views on such topics as memory politics, attitude towards the Soviet past, or the 20th century’s history. It is pretty often artists and cultural workers who elaborate and deepen these discussions.

What do you think, what can be the reason behind this?

Compared to the Western context, culture is not so much structured as a separate field here. It might seem anarchistic, however, it also indicates that it’s only emerging institutionally and autonomously. Due to this, one can find many unexpected routes and unwalked paths in culture and arts.

The cultural field in Ukraine with some exceptions works independently from state financing and in this way, it is self-regulated. Even if you have some pressure from the state, it cannot really control you. Of course, it has its pros and cons. Culture in Ukraine doesn’t have an institutional protection, which means that anybody from the outside can intervene or impose some agenda on it. It also complicates the functioning of the field as you can’t rely on sustainable structures in the mid-term. On the other hand, due to the absence of clear borders, there is a constant interconnection and interrelation between culture and other social fields.

“Being an artist or a cultural worker in Ukraine is not so much a profession, but rather a mission.”

These features make possible to create artworks and exhibitions that work out as direct political statements and can provoke reactions from political groups. This politicality is being easily swallowed by the art system in the West. You can do whatever you want there, but actually, nobody pays serious attention to it. In many European countries, journalism or public discourse can offer political alternatives, perhaps except Hungary, unfortunately. In Ukraine, this alternative is culture and I think it unavoidably impacts the way politics is being thought of.

These potentials can be empowering, but at the same time, they might put too much pressure on the shoulders of artists and cultural workers.

Working in the field of culture in the West usually means that it’s just your profession. There are paved routes and you follow what had been already prepared for you. In Ukraine, as I said, there are no clear paths. You are testing different limits and it can provoke some political changes or reactions. It indeed means much more pressure and responsibility. Being an artist or a cultural worker in Ukraine is not so much a profession, but rather a mission. It means you have some political stance, and that is why you are in the field. You might not have political power, but your mission is to conceive and transmit something in order to change an unjust predicament. For me, it resembles the phenomenon of the East European intelligentsia in the second part of the 20th century.

Transperiphery Movement – Global Eastern Europe and Global South. Curated by Eszter Szakács and Zoltán Ginelli. Allied – Kyiv Biennial 2021. The House of Cinema, 16 October – 14 November 2021 Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

Transperiphery Movement – Global Eastern Europe and Global South. Curated by Eszter Szakács and Zoltán Ginelli. Allied – Kyiv Biennial 2021. The House of Cinema, 16 October – 14 November 2021 Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

Divided – Shared Solidarity – Political Mobilization and Visual Agency in Belarusian Protest Movement 2020-2021. Lecture by Almira Ousmanova. Allied – Kyiv Biennial 2021. The House of Cinema, 16 October – 14 November 2021. Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

Divided – Shared Solidarity – Political Mobilization and Visual Agency in Belarusian Protest Movement 2020-2021. Lecture by Almira Ousmanova. Allied – Kyiv Biennial 2021. The House of Cinema, 16 October – 14 November 2021. Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

You criticized Western institutions for their hesitation to take action and step beyond their comfort zones in supporting Ukraine in the ongoing war. As you wrote, they “have simply resorted to a white cube radicalism and self-satisfying humanitarianism.” I found the phrase “white cube radicalism” a very talkative expression and in my understanding, it is exactly that well-pathed and sometimes very bureaucratic system that can make it difficult for art to achieve an impact beyond its boundaries.

First of all, I have to stress that without humanitarian help and solidarity actions that have come from various cultural institutions in the EU and elsewhere we would not survive. This support is highly appreciated and very valuable. For me, political engagement is not just some fashionable radical chic discourse that is widely shared in the art field. In the article, I pointed out that it also requires trespassing the boundaries of the cultural field and going beyond them. It is fine to share some radicality at the conferences or within exhibitions, but if you want to achieve political goals, you have to go outside. If you simply stick to the institutional borders trying to preserve what is inside, that leads to the dwindling of the field. I’m not talking here only about the Ukrainian case. It is no coincidence that in many Eastern European countries, like Hungary or Poland, cultural institutions are hijacked by right-wingers and such people are appointed as their chiefs or artistic directors. When this wave of right-wing authoritarianism comes to culture, it’s already a sign that it’s too late. In order to preserve the freedom that cultural institutions have obtained in their own field, they have to go outside and fight for the cause.

“When this wave of right-wing authoritarianism comes to culture, it’s already a sign that it’s too late. In order to preserve the freedom that cultural institutions have obtained in their own field, they have to go outside and fight for the cause.”

During the last months of this war, many institutions were not ready to do so even if it wouldn’t demand any radical actions. I don’t want to overestimate but culture can work as a pretty powerful tool. You can make a political stance with all the instruments you have there, putting more pressure on your publics and authorities, demanding more actions from the government, etc. It means not only dealing with politics within the cultural field but also making political actions outside it as a cultural worker. Unfortunately, this chance in Europe has been lost.

This “white cube radicalism” is symptomatic indeed to understand the way how the cultural field works institutionally in Europe. On the one hand, you have big, elephant-like institutions that are afraid of independent activity. Their modus operandi does not allow any alternative to emerge, they basically follow governmental lines.

Open Call (For Opinions). Theatre exhibition by Studio Laif (Czech Republic/Slovakia). 17 – 18 November 2019, Metaculture, Kyiv. Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

Open Call (For Opinions). Theatre exhibition by Studio Laif (Czech Republic/Slovakia). 17 – 18 November 2019, Metaculture, Kyiv. Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

On the other hand, you find what I call horizontal dictatorship. I refer here to institutional collectives and curatorial groups, which are proclaiming and sharing the modus of participatory democracy. As all the decisions have to be made in a collective manner, they endlessly discuss every detail and at the end of the day, they arrive nowhere simply because they all together cannot decide on anything. So in both cases, whether an institutional form is centralized and vertical or horizontal and participatory, it is totally disfunctional for the political cause. Even if we take into account their institutional dependence on financing or the fear of expressing an opinion that might contradict the government’s position, it’s still striking as they basically don’t risk anything. So the question arises: When would they react then? In the East, we have the hijacked cultural institutions, and in the West, we have those sticking to their internal comfortable gardens. For me, it’s a pessimistic sign that the cultural field in Europe is not really capable to introduce any proposals regarding political or societal alternatives. It undermines its own modus operandi and is losing its own ground. European culture simply surrenders its political frontlines, unfortunately.

Coming back to the Kyiv Biennial, the second edition was called The Kyiv International and focused on the idea of a political International and its emancipatory potential. Looking at the history of the Biennial, I observed a constant attempt to find a proper language to explain what is going on in Ukraine, and what is the Ukrainian experience. Different editions for me also mirror a persistent search for international partners, who could be an ally in building a solidarity-based alternative future. I think it might not be a coincidence that you found partners in East Europe, which led to the establishment of the East Europe Biennial Alliance (EEBA) in 2018. Do you think this translation works better in East Europe? Can the common experience of the Soviet past help to speak a common language?

Personally and politically, I am a strong believer in internationalism as such, I don’t think nation states can survive global tendencies or be well off separately. It was rather an illusion of the late 19th century. An internationalist umbrella allows better things to emerge, and from this point of view, it’s a very natural intention for Ukraine to join the EU.

The Kyiv International was a kind of translation laboratory. It can be explained through the idea of a different but shared past, which shows that a major division line in Europe still runs between West and East. We deliberately named our Biennial Alliance the East Europe one referring to indeed the whole East of Europe, not just Eastern Europe (usually shyly covered under the title ‘Central’) but also Europe’s post-Soviet East as well as the so-called Middle East, including Central Asia, the Balkans and North Africa, with which we were very much connected in the Cold War times. These (semi-)peripheries are a decisive region of Europe, where its fate has been fought for and is literally being decided on the battlefield at the moment.

This idea of a different but shared past is also connected to colonialism and the processes of decolonization. Decoloniality today became a fashionable trend and almost every cultural institution in Europe is conducting something on the matter. For the Western metropoles, the discourse of (de)colonization is very much grounded on the premise of the colour of skin and the history of maritime empires. But there is a constant inability to recognize colonialism next to your nose in the present. It appears that Western political and cultural entities are not able to apply the lexicon and matrix of decolonial analysis to Europe’s East.

The lack of agency or subjectivity is what is typically ascribed by the colonizer to the colonized. The same attitude is being often preserved in the West treating the East European experience as a secondary one. The West is regarded as a real, civilized and polished Europe, whereas the East is a second-hand one, with the remains of communism, totalitarianism, etc. Since the collapse of the USSR, the main task that Eastern countries have been assigned to was to catch up with the West. The experiences of the real East Europe have been disregarded for a long time as it was always Moscow, the other imperial metropole, that was the main point of reference for the West in the East. Within the framework of the EEBA, we aim to present alternative discourses about this region, its history and subjectivity, challenging those typical (neo)colonial approaches.

With the EEBA, you recently launched a new series to discuss Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine. You curated the first public program Armed Democracy, in which this aspiration of getting a new subjectivity to East Europe had also a central role. Organized in the framework of the second edition of Biennale Warszawa, the program consisted of lectures and discussions and covered such topics as the importance and heaviness of documenting Russian war crimes, the characteristics of militant democracy, and the trauma of decolonization, among others. The program took an important endeavour by looking at the war from the perspective of the East European region and analysing the Russian aggression in this broader context. How did you approach this complex topic?

The Kyiv International. Kyiv Biennial 2017. 20 October – 26 November 2017, Institute of Scientific, Technical and Economic Information. Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko

The program reflected upon the new realities, which emerged along with this war, as well as the challenges, such as militarization or new fascist threats. The EU was simply not prepared for that as all those things were supposed to be part of a distant past. With regards to East Europe, these countries hadn’t been taken seriously when they expressed their worries and fears. Now we heard from different European leaders that if those sanctions and reactions, which followed the full-scale invasion, would have taken place after Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014, we would not have this war. In contrast to the EU, which is always late, Armed Democracy was based on the idea of being capable of acting ahead.

Euromaidan – One of the remaining barricades on Maidan. Kyiv, 6 April 2014. Photo: Michael Kötter

Maidan Nezalezhnosti at Dusk. Kyiv, 12 April 2014. Photo: Michael Kötter

Kyiv Central Square (Maidan). 6 hours before bloody crackdown of students at 4:00 am 30 November 2013. These event marked the beginning of the military intervention of Russia in Ukraine 29 November, 2013. Photo: Visavis

Within the program, we tried to overview various aspects of Russia’s war of annihilation against Ukraine and Europe. We saw that some of the former discourses might not work in the current context and tried to draw a cognitive mapping of theories, political approaches and possible terminology to analyse the ongoing atrocities. It was an attempt by theoretical and analytical means to understand what works, what is applicable to the world today, and what kind of analysis is the most efficient to apply. In general, our main question was: How could it happen that we’ve got another fascist war of aggression on the European continent in spite of all ‘never again’ claims?

First published on 21 December 2022 on balkon.art.

This text is protected by copyright: © Kinga Lendeczki / Balkon. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team. Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Open Call (For Opinions). Theatre exhibition by Studio Laif (Czech Republic/Slovakia). Photo: Oleksandr Kovalenko