Ukraine is practising active cultural diplomacy to communicate a better understanding of the country. One might like to think that art is apolitical. But that’s impossible. Art doesn’t exist isolated in a vacuum; it is part of life in which politics plays an essential role. Art is social: it is a form of expression, a reaction to the outside world. Art is also often used for political purposes, particularly for foreign policy aims. This type of political instrumentalisation is called cultural diplomacy.

Cultural diplomacy

Prof. David Clarke defined cultural diplomacy as “a policy field, in which states seek to mobilise their cultural resources to achieve foreign policy goals”. The term is closely related to “soft power”. Soft power is a form of exercising power, using cultural and ideological influence to achieve policy goals. In contrast to hard power, neither economic nor military resources are applied. Nowadays, many academics deal with the term soft power from the perspective of “conceptualising the potential of culture in terms of international politics”.

Cultural diplomacy is not necessarily negative; after all, a range of cultural projects can enable one to learn something new or to expand one’s world view. Examples of this are the annual Ukrainian Ball in Vienna and the Austrian Film Week in Kyiv, or the “Moscow Village” Christmas market on the Vienna University campus in 2021. There, for example, one could order borscht, a traditional beetroot soup, the Ukrainian recipe for which has been included on the UNESCO Cultural Heritage list – but only after a conflict between Russia and Ukraine. At the market, however, there was no mention of its Ukrainian origin.

Here is where Russia’s cultural diplomacy starts to become problematic. Russia likes to make use of soft power and often abuses it. The problem lies in the fact that a number of cultural goods – whether traditional food such , or literature or art – are not presented by Russia as authentically Ukrainian, Belarusian, Georgian etc., but as part of the joint cultural heritage of the great Russian-language area. In this way, Ukrainian culture is perceived as represented solely through a Russian perspective.

Is the Russian avant-garde Russian?

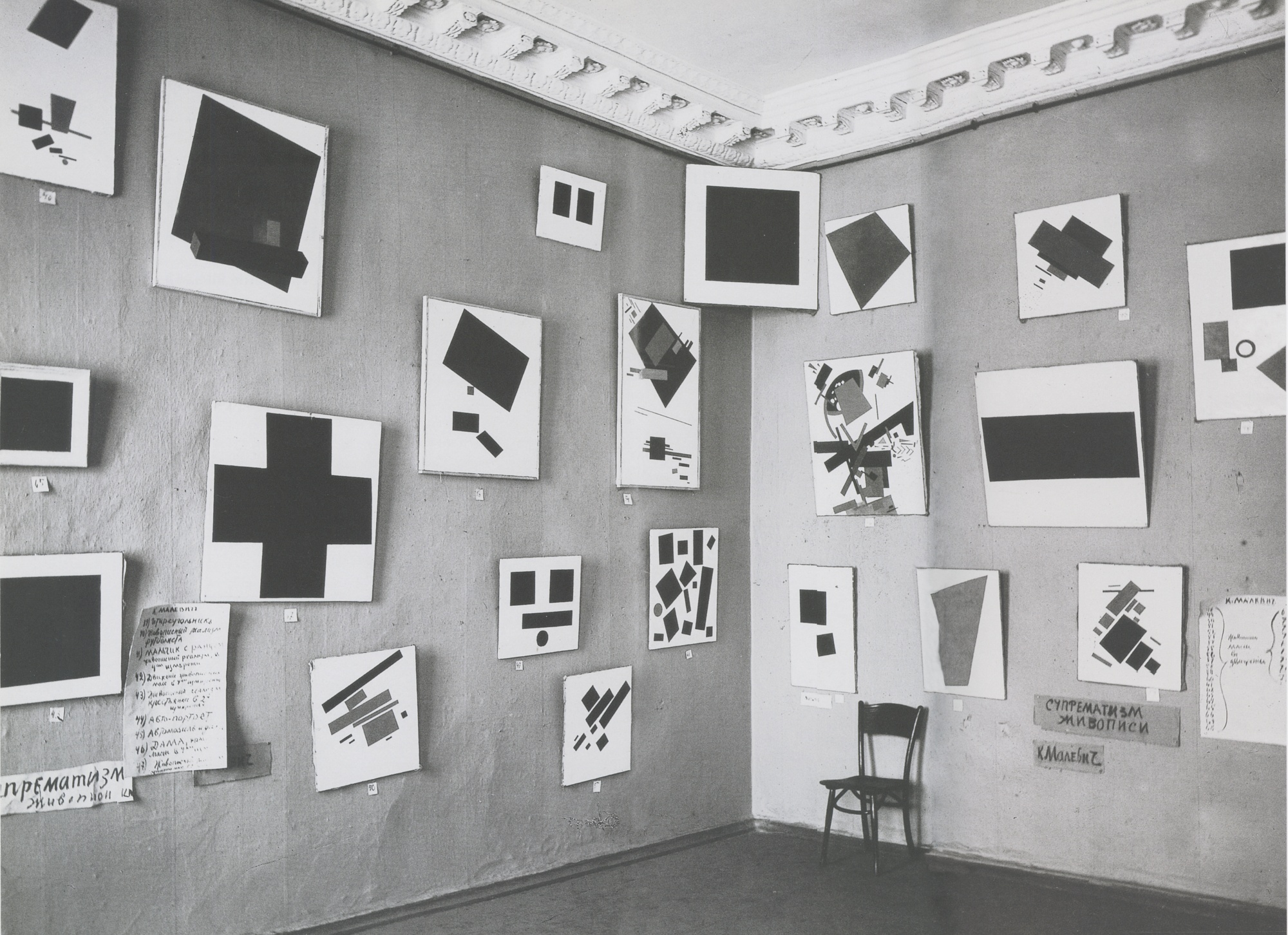

It may sound odd, but in this sense the fate of Ukrainian artist Kazymyr Malevych was similar to that of borscht. Malevych was a painter, a representative of the avant-garde and inventor of Suprematism. He is also creator of the famous picture Black Square, now viewed as a milestone of modern art. Kazymyr Malevych, born in Kyiv, described himself as Ukrainian on official documents. Yet he is still identified as a Russian artist and the main representative of the Russian avant-garde.

The Suprematist works of Kazymyr Malevych. Photo: Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons

As part of the Monet bis Picasso exhibition currently showing in Vienna’s Albertina Museum, a section is titled “Avant-garde in Russia”. This room includes, among others, works by the Ukrainian Malevych and by Chagall, who was born in Belarus. The picture captions give no information on the artists’ national identity, other than that one was born in Kyiv and the other near Vitebsk. The museum even gives Malevych’s name as “Kazimir Malevich”, which is in fact the Russian translation of the artist’s Ukrainian name.

Art historian Jean Claude Marcadé said in a 2018 interview on this topic: “I have been fighting for decades against Russian cultural aggression, which is now becoming more acute in the current political situation. Active Russification is continuing. In all my books and articles, I use the term ‘Ukrainian’. Russians do not use it, saying for example ‘born in Kyiv’ or hinting that Malevych was Polish”.

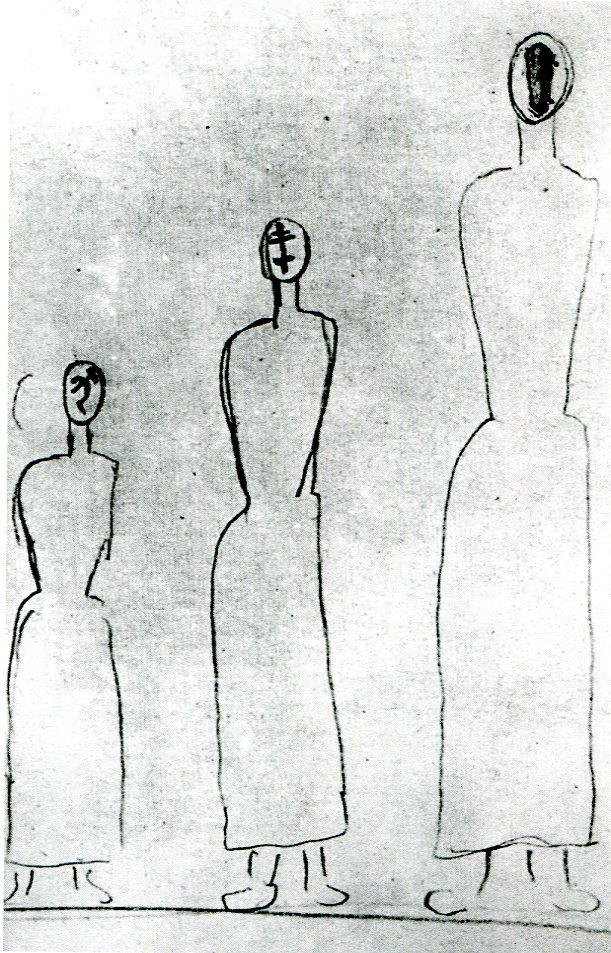

Malevych is referred to as a Russian artist (or a Russian artist born in Kyiv), although he spoke Ukrainian, was influenced by Ukrainian motifs, and even created images on the topic of the Holodomor (the famine in Soviet Ukraine caused by human action). This work is titled “Where hammer and sickle are, there are death and famine”.

The work of Kazymyr Malevych “Where hammer and sickle are, there are death and famine” depicts three figures whose faces are replaced with a hammer and sickle, a cross and a coffin. Photo: Public Domain / Ukrainian Art Library

Malevych wrote about his home city Kyiv: “… I feel more and more like returning to Kyiv. Original and unique Kyiv is vivid in my memories. Buildings from coloured bricks, mountainous terrain, the Dnipro river, boats (…) City life influenced me.”

The methods of Russian cultural diplomacy have led to the fact that many artists who identified as Ukrainians have been presented as Russian. Other examples apart from Malevych are Davyd Burliuk and Oleksandr Archypenko. This fact illustrates the the consequence of keeping quiet about the Ukrainian context in the avant-garde.

That does not mean, however, that the oeuvre of Ukrainian artists is located exclusively in the Ukrainian context. Ukrainian artist Nikita Kadan says on this, “The appropriation of the avant-garde by national positions at the level of practical action appears possible, but then it would no longer be the avant-garde. The movement’s universalist significance, its orientation towards a post-national world – all that would be impossible”. This also means, however, that these works should not be perceived as Russian.

Art that legitimises political independence

Russian cultural diplomacy, combined with lack of Ukrainian cultural policy, has succeeded over decades in establishing the image of one people with a shared culture, traditions and language. As one of the results, many people were convinced that Ukraine, even if not part of Russia, was definitely very similar to Russia.

Artwork by Nikita Kadan

Most people have heard of the famous Russian Bolshoi ballet or well-known Russian literature. One knows about Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky. In a similar way, Malevych the Ukrainian or Chagall, born in Belarus, are registered in the collective memory as Russians. Last but not least, Russian institutions lobby for and support this process.

“Carol of the Bells”: a Ukrainian success

Russia has been exercising soft power for centuries. Nevertheless, Ukrainian cultural diplomacy can also point to some successes of its own. The most significant example is the song “Carol of the Bells”, originally a Ukrainian folksong titled “Shchedryk”.

The melody of “Shchedryk” was created by Ukrainian composer Mykola Leontovych. The song was translated into several languages. In 1936, when Ukraine was already part of the Soviet Union since 14 years, Peter J. Wilhousky, an American composer of Ukrainian origin, wrote the English lyrics and adapted it as a Christmas carol, which made “Shchedryk” world-famous as “Carol of the Bells”.

Ukraine declared its independence in 1919 Already in 1918 the Ukrainian People’s Republic declared its independence. At that time, the territory of this republic included the areas of modern central and eastern Ukraine. After the collapse of Austria-Hungary, the western part of the modern Ukraine created its own state under the name the West Ukrainian People’s Republic, whose borders were laying in the areas of Eastern Galicia, Northern Bukovyna and Transcarpathia. Only a year later, on January 22, 1919, the two republics united under the name Ukrainian People’s Republic. As a result, the united Ukraine emerged within the borders known today. Although the Ukrainian Soviet Republic was proclaimed in the same year, the army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic fought for the existence of the state until 1920. Since the unification of the two republics is considered the birth of modern Ukraine. Hence, the year 1919 was given as the date of the Ukrainian declaration of independence in this text. . Even before that, the Russian Soviet Republic had begun its Bolshevik expansionist policy. This period is also referred to as the Red Terror. Symon Petliura, then one of the most important political figures in Ukraine, sent a choir on a world tour at the time of the Red Terror. He believed that this cultural diplomacy could show the world that Ukraine is a sovereign country.

The Ukrainian Republican Capella gave a concert in Vienna in July 1919. The Viennese monthly journal Musica Divina wrote, “The cultural maturity of Ukraine is intended to legitimise its political independence”. The Ukrainian Republican Capella visited ten countries and gave over 200 concerts. Many artists, politicians and VIPs wrote to the Capella in support.

Ukrainian artists’ counteroffensive

Just like a hundred years ago, Ukrainian artists are now fighting not only at the front, but also in the cultural field. However, Ukrainian cultural diplomacy looks different in 2022 from how it appeared in 1919, because it has more outside support. World-famous celebrities come to Ukraine to show their support; they are collecting donations, starting aid initiatives and spreading information about the country.

Renowned historian Timothy Snyder not only made his Yale lectures on Ukraine’s history, “The Making of Modern Ukraine”, freely available to all; he also teamed up with actor Mark Hamill as ambassadors of the United 24 initiative. United 24 is a donations programme of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy through which money can be donated to the official accounts of the Ukrainian national bank, where they are used by ministries to cover costs for the most important tasks. Sean Penn donated his Oscar statue to Zelenskyy. David Letterman interviewed Zelenskyy and shared jokes by Ukrainian stand-up comedians via his social media channels. Pink Floyd recorded a song with Ukrainian singer Andriy Khlyvnyuk (Boombox).

These actions would have been unimaginable not just a century ago – but even two years ago. Ukrainian artists are not only travelling to Europe to collect donations, but also to report on the situation in Ukraine and to present Ukrainian culture to the world – like Serhiy Zhadan, winner of last year’s Friedenspreis des deutschen Buchhandels (peace prize awarded by the German Publishers and Booksellers Association). He sees every concert and every appearance as an opportunity to speak about Ukraine, its language, music, literature, people and of course about the war.

Launching initiatives

Artists such as Ukrainian curator Vasyl Cherepanyn are working on initiatives to help Ukrainian artists to draw attention to the problems in their country. The organiser of the Kyiv Biennial is now trying to help evacuate museum collections and works of art from heavily bombed areas.

Cherepanyn says of himself that he is active on the international culture and information front. Working with other colleagues of the Visual Culture Research Center, he launched the Emergency Support Initiative, a support programme for artists, curators and others who are currently in need. Office Ukraine, Shelter for Ukrainian Artists is a similar initiative in Vienna, Graz and Innsbruck.

On the topic of the Russian boycott and its consequences for Russian culture, Vasyl stated in an interview with Austrian daily DER STANDARD, “This war of aggression didn’t happen overnight; the process has been going on for many years. Where were the Russian cultural institutions during all that time? They were happy to benefit and accepted everything that happened up to then, from restrictions to press freedom and freedom to demonstrate, up to the assassination of opposition figures”.

Dialogue through art

Culture can only exist within a society; therefore it reflects the culture’s discourses. Like anything else, cultural diplomacy can be used for propaganda and for twisting the facts. Many decades of Russian soft power in the form of cultural diplomacy have left impressions that, presumably, will not disappear within one year.

For the future, it is important that Ukrainian culture is represented and that its representatives are listened to. Ukraine’s cultural diplomacy is currently playing, more than ever, a significant role. It has a big meaning when talking about creating a better understanding of the country as well as about its struggle for independence. Current Ukrainian cultural diplomacy is a lively dialogue between Ukraine and the world via art. And this dialogue must continue.

Literature

Biedarieva, Svitlana (2021). Contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic art: political and social perspectives, 1991–2021. Ukrainian Voices, vol. 14. Stuttgart: ibidem.

Gerbish, Nadiyka / Hrytsak, Yaroslav (2022). A Ukrainian Christmas. London: Sphere

Gruber, Klemens (2020). Die polyfrontale Avantgarde: Medien und Künste 1912–1936. Wien: Sonderzahl.

Minakov, Mykhailo / Kasianov, Georgiy / Rojansky, Matthew (eds.) (2021). From “the Ukraine” to Ukraine: A Contemporary History, 1991–2021. Stuttgart: ibidem.

Plokhy, Serhii (2022). Die Frontlinie. Warum die Ukraine zum Schauplatz eines neuen Ost-West-Konflikts wurde. Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Snyder, Timothy (2018). The road to unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America. New York: Tim Duggan Books.

Susak, Vita (2010). Ukrainian artists in Paris: 1900–1939. Kyiv: Rodovid Press.

Original in German. First published on 13 December 2022 on derstandard.at.

Translated into English by Barbara Maya.

This text is protected by copyright: © Olena Levitina / Der Standard. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team. Copyright information on pictures and graphics are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: “The Beast Goes for a Walk” by Mariia Prymachenko, a Ukrainian naive artist and icon of Ukrainian identity. Photo: Olena Levitina