Poland’s public tries to clear the air

A number of economic and bureaucratic bottlenecks means it will take several years to disperse the smog.

03 May 2022

Originally published

18 February 2021

Source

Public awareness of Poland’s air quality problem is rising, but a number of economic and bureaucratic bottlenecks means it will take several years to disperse the smog that blankets the country’s towns and cities.

One of Warsaw’s five air-monitoring stations is perched on a fenced-off hilltop between rows of apartment buildings and a primary school playground. A miscellany of silver chimneys sprout from a shack roof. Each pipe sucks down different air samples for humming computers to digest. Some fall on snow-white filters for lab tests, others are scanned with laser beams to estimate concentration every six seconds.

“We do it to see what life is like in a compound like this,” says Tomasz Klech, who heads the air-monitoring lab at the Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection (GIOS) in Warsaw, as he unbuckles the pipes to inspect the blackened filters. The news he delivers has often been worrying; as temperatures dropped in January, concentrations of particulate matter in the air near Warsaw hit 1,300 per cent of health norms.

As Poland’s problem with air quality comes to light with better data and green activism, public awareness is rising. Yet a number of economic and bureaucratic bottlenecks mean that it will take several years to disperse the blanket of smog that hangs over the country’s towns and cities.

A very Polish smog

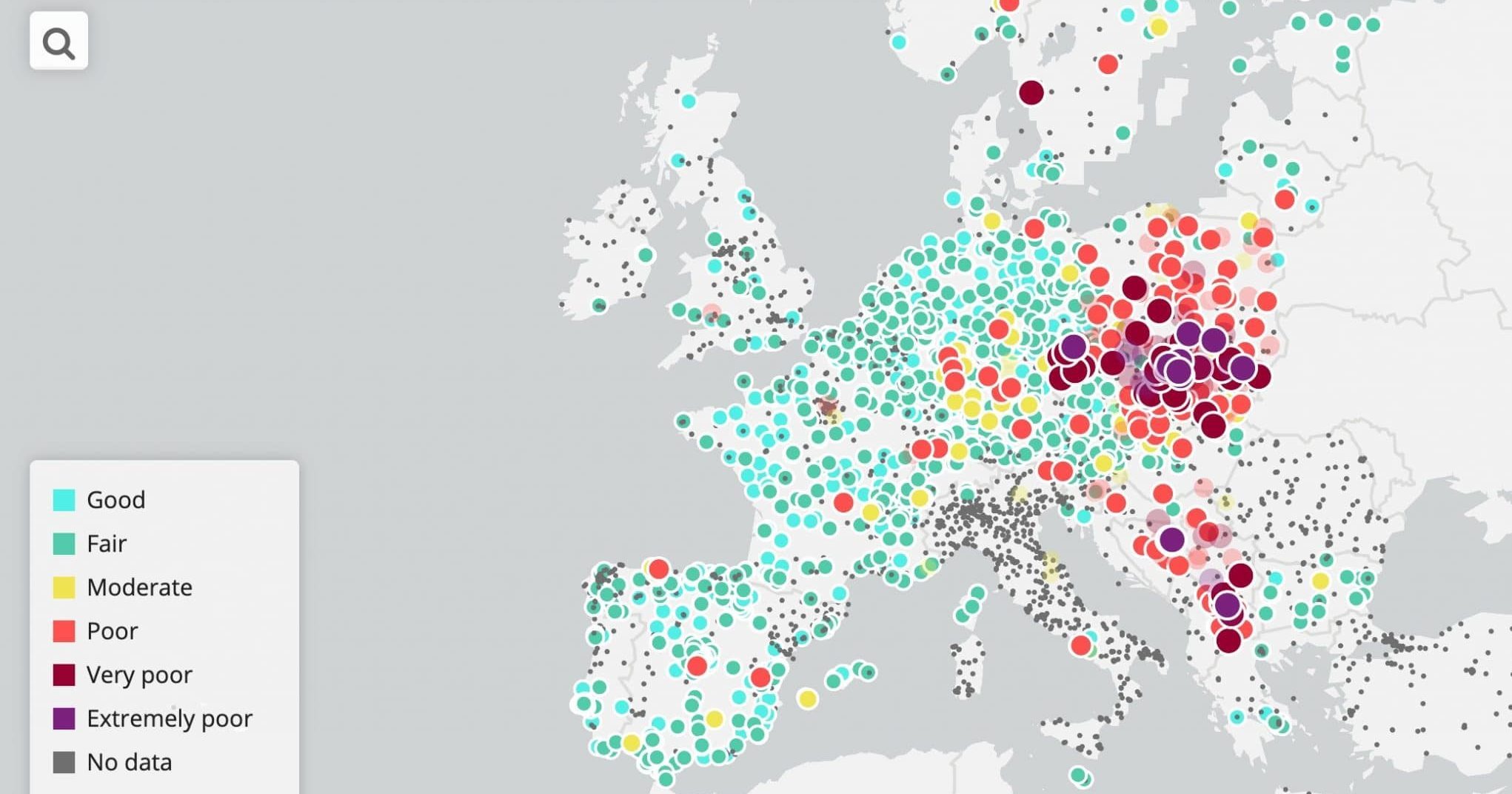

Poland has the EU’s worst air, according to a report published by the European Environment Agency (EEA) in November [2020, ed.]. While Balkan countries score worse in terms of average years of life lost across reports, Poland leads the way in its wider geographical spread.

Tomasz Klech, who heads the air-monitoring lab at the Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection (GIOS) in Warsaw. Photo: Maria Wilczek

Poland’s smog is mainly caused by its legacy of burning cheap fuels to heat homes. The problem is most acute during the winter, when temperatures drop and chimney fumes envelope residential areas. This year’s [2021, edit] peak pollution on 18 January coincided with a temperature drop below -20° Celsius, when the Polish city of Wroclaw briefly had the world’s worst air, according to IQAir’s ranking.

The result is a unique toxic cocktail. “Poland is dusty smog,” Professor Grzegorz Wielgosinski, who heads the environmental engineering department at the Lodz University of Technology, explains. It contains a lower concentration of sulphur dioxide than in the famous London smog episode of 1952, but more carcinogenic benzo(a)pyrene and heavy metal dust.

The bad air causes an estimated 45,000 premature deaths in Poland each year.

These grains of matter, no larger than 10 micrometres, can enter the lungs and bloodstream. The bad air causes an estimated 45,000 premature deaths in Poland each year. In October [2020, ed.], a study found that children in the southern city of Rybnik had on average four times more harmful substances from burning fuels in them than counterparts in Strasbourg in France.

European Air Quality Index on 16 February 2021. Graphic: European Environment Agency

Unlike London’s foggy sheets on days of low atmospheric pressure or the tawny smears in the peak of summer in Los Angeles, smog in Poland occurs with high-atmospheric pressure and little wind. “It is even worse on sunny days,” Professor Wielgosiński tells BIRN, as a blanket of warmer air traps cold currents below, creating a so-called “temperature inversion” that causes fumes to accumulate.

Old heaters and dirty curtains

Dawid Fojcik can see the smog out of his window. He lives in Poland’s coal heartlands of Silesia, where in his area the daily intake of carcinogenic benzo(a)pyrene is equivalent to smoking 16 cigarettes, according to activists.

“My wife has to keep washing the sheer curtains because they get dirty whenever we open the windows,” says Fojcik. Yet he has grown used to the biting smell and hazy sight: “People in Silesia don’t see the smog, many are convinced that it doesn’t exist.”

What Fojcik sees in his neighbourhood is even more clearly viewed from space. On wintry days, Poland’s contours can be made out on satellite maps by the country’s cover of fumes. Neighbours, like Slovakia and the Czech Republic, have switched to using cleaner natural gas – something which has been more straightforward to achieve across their comparatively smaller territories.

Dawid Fojcik lives in Poland’s coal heartlands of Silesia, where in his area the daily intake of carcinogenic benzo(a)pyrene is equivalent to smoking 16 cigarettes, according to activists.

Yet Poland’s affection for coal goes back to its widespread use during communism, when it served as a prized export and fuelled the country’s own industrial growth. Today, the country is still the EU’s largest producer of hard coal. Despite mounting European pressure, reform has been resisted by the powerful mining lobby. As a result, Poland is the only European country to burn more coal for heating today than three decades ago.

However, the problem is not so much coal as it is the dirtiest varieties that are commonly used for heating. This is especially true in the country’s industrial south side, where products such as slurry and culm are still peddled near mines. People living in old, poorly insulated houses often opt for the cheapest combustibles, including wood and even rubbish, which is illegal in Poland.

A pair of artificial lungs touring Polish cities and towns, operated by Polish Smog Alert (PAS), a social movement that brings together activists fighting for the improvement of air quality. Photo: Film still from PAS video

“Elderly people sometimes don’t even use coal, they burn old rags, paper, anything – because that is cheapest,” says Bartłomiej from the Silesian town of Żory. He often sees his neighbour search for wooden planks and slabs in the communal bins outside. “He tries to burn clean wood, but if he only manages to find oiled or painted pieces, he’ll throw them in too,” Bartłomiej, who asked for his surname not to be printed, tells BIRN.

To break the cycle, Bartłomiej recently changed three coal heaters in the houses he owns to gas boilers. The costs, he says, are notable. On top of each heater being 4,000 zloty (890 euros), additional costs come from having to replace heating pipes – at 20,000 zloty (4,460 euros) per house – as well as the later plastering, painting and cleaning.

“They only advertise changing the boiler, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg,” he says. Heating will also be more expensive now, rising from 2,400 zloty (535 euros) for his annual coal heap, to about 700 zloty (155 euros) per month for gas.

A travelling pair of lungs

A two-metre pair of lungs stands in the central square of Rybnik. The metal cage is wrapped in a pearly fabric. Internal ventilators pump air through, catching particulate matter on the crisp sheets of interlining. Day by day, the material becomes darker.

“The stunt is meant to visualise what we breathe,” says Piotr Siergiej, spokesman for Polish Smog Alert (PAS), a social movement that brings together activists fighting for the improvement of air quality in Poland. “Despite growing awareness, the problem of smog is often neglected, usually in places where there are no measuring stations.”

His group has towed three such pairs of “lungs” around 18 Polish towns to showcase the effects of pollution. Since launching a single installation in 2020, the group has received “many phone calls from various local authorities” asking to display the lungs in their town.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Poles began wearing face masks in cities on dirtier days.

PAS has also set up simple devices to count particulate matter in towns “about which we have no data”, and it works with local media to broadcast daily measurements. Professional equipment like that used at the state-owned station, required for official EU measurements, is rare and comes at a cost of up to 800,000 zloty (180,000 euros) per set-up.

Thanks to stunts by dozens of activist groups across Poland, public awareness around smog is improving. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Poles began wearing face masks in cities on dirtier days. In a new study, 60 per cent of respondents said that the gravest environmental issue in the country today was its air quality, and a majority of respondents correctly identified home heating as the main contributor.

“Five years ago, people would say that it was caused by industry or cars,” Siergiej tells BIRN. These, however, only account for 20 per cent and 8 per cent, respectively, of the country’s PM10 particulate matter. “Yet this knowledge does not yet translate into our actions as citizens,” he stresses.

Greenpeace activists put a mask on the French General Charles de Gaulle Monument to protect him against smog in Warsaw, Poland, 12 March 2015. Greenpeace called to draw attention to the problem of the high level of air pollution in Warsaw and its impact on the health of Warsaw residents. Photo: Marcin Obara / EPA / picturedesk.com

Other activists have taken matters up a notch and launched court proceedings against the state for its negligence over smog. In one such case that could see a final verdict in February [2021, ed.], Grażyna Wołszczak-Sikora, a Polish actress among a group of celebrities who have taken similar steps, has asked for compensation for damages inflicted by insufficient government action. Local courts have so far held up their side. If successful, the compensation will be donated to charity.

“The intention of the campaign is for public figures to speak out,” says Radosław Górski, a lawyer based in Warsaw leading the case. “For the first time, this issue – hitherto only raised by journalists – has become a legal dispute,” he says, noting with satisfaction that “those responsible… have had to justify themselves from the position of a defendant”.

Whiffs of change

Change has largely been driven by local authorities. “Krakow is undoubtedly a leader in terms of measures taken to improve air quality… Other cities and towns are following our solutions,” the city’s mayor, Jacek Majchrowski, tells BIRN.

Since banning the burning of coal and wood in 2019, a fresh study in January [2021, ed.] showed that the air in Krakow has been improving much faster than in nearby areas. “Over the last seven years, the concentration of particulate matter has dropped by half, with similar results for carcinogenic benzo(a)pyrene,” points out Majchrowski.

The mayor credits the local subsidy scheme for heater replacement and compensation for higher heating fees, to which the city has allocated over 350 million zloty (78 million euros). Krakow has also launched a mobile application to inform the police about illegal incineration. A number of cities have also set out smog-sniffing drones to monitor chimneys. And on days with particularly bad air, public transport in the city is free to encourage its use.

Yet much of the trumpeted improvements in air quality may actually be the result of another trend of recent years: warmer winters. “Many institutions will report that air quality has improved,” says Klech, the environmental engineer. “But the question is whether the improvement is driven by their actions, or by warmer weather.”

At the root of the problem is that much of the heating technology and acquiescence around bad practices has not changed. In the past two years, only around 70,000 of Poland’s 3 million dirty incinerators have been replaced, according to PAS. This is in part due to the government’s flagship “Clean Air” subsidies scheme being marred by poor management and low-take up.

Paweł Mirowski, deputy director of the state fund (NFOŚiGW) overseeing the subsidies, tells BIRN that the scheme has been “constantly improved”, through simplified application forms, better local communication and the recent launch of subsidies co-sponsored with local authorities. On 8 February [2021, ed.], the government announced that it would spend 100 million zloty (22 million euros) on advertising the program, which as of now has an unhurried timeline lasting until 2029.

Slow change is stirring in anticipation of a stronger gust of wind. In 2018, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled that Poland had infringed EU law on ambient air quality, with the European Commission stopping short of financial penalties. Klech notes that, for now, domestic heaters are not included in calculations of how much carbon countries emit within the European Trading Scheme (ETS). “But that could change,” he warns.

First published on 18 February 2021 on Reportingdemocracy.org, a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.

This text is protected by copyright: © Maria Wilczek / Reporting Democracy. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: View from the Kościuszko hill in Kraków in October 2013. Photo: (CC-BY-SA-3.0) Anna Książek / Adam Rżysko / Wikimedia Commons