12 January 2023

Originally published

15 April 2021

Source

How did “LGBT-free zones” become the pre-eminent symbols of Poland’s homophobic turn? The story of a slogan from the culture wars that went mainstream.

If Poland’s “LGBT-free zones” were to form a country, Lublin would make a strong contender for capital. The provincial city, 150 km from Warsaw, is at the epicentre of the phenomenon that gave rise to the zones, sweeping through local governments across south-eastern Poland. In March 2019, a small town outside Lublin was the first place to approve a declaration – an apparent rejection of “LGBT ideology” – that would eventually become a basis for the zones.

Please note: The text was published in the framework of the Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence in April 2021. Despite that fact that it is not a recent investigation, we are convinced that both article and topic are still important and newsworthy. Therefore we decided to publish it in our magazine. At certain points of the text we have edited dates and time frames to provide a clear picture of the information that has been researched. Yet, the core of the article has remained unedited and is based on the original version.

In April 2019, the administration of the surrounding province, also named Lublin, approved a similar declaration. The city of Lublin is the capital of the province, and like every good capital, it holds itself apart from the region it represents. “LGBT-free zones? I don’t care about this bullshit,” said Milosz Zawistowski, an artist and part-time bartender from the city. “Lublin city has as much to do with Lublin province as Moscow has to do with the rest of Russia. It doesn’t matter if you’re gay here.”

Lublin was the first of five provinces to meet the criteria for being an “LGBT-free zone”. The provinces are concentrated in Poland’s relatively under-developed south-east, the electoral heartland of the governing national-conservative Law and Justice party. The emergence of these zones, spanning roughly a third of the country’s territory, has coincided with Law and Justice’s use of increasingly homophobic rhetoric to mobilise its electoral base. Over the past two years [2019-2021, editor’s note], the party has won tightly-contested parliamentary and presidential elections with campaigns that portrayed gay people as paedophiles and talked up LGBT rights as an alien ideology menacing family, society and the Catholic faith.

Against a backdrop of this rhetoric, the “LGBT-free zones” have gained international notoriety. In Brussels and beyond, they are regarded as a worrying marker of Poland’s descent into illiberalism – the ultimate territorial expression of state-sponsored homophobia. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has referred to them as “humanity-free zones”, while Joe Biden re-tweeted and echoed her comments when he was campaigning to become US president. The European Parliament has also condemned the zones, most recently on 11 March [2021, ed.] by passing a resolution declaring the entire EU to be an “LGBTIQ Freedom Zone” – a symbolic riposte.

However, the zones themselves have a paradoxical quality that is not quite reflected in the “LGBT-free” tag. In the eastern cities that are home to some of the largest LGBT populations – Lublin, Białystok and Rzeszow, for instance – the label is at once accurate and not. These cities lie within areas that meet the criteria for inclusion within the zones: their local authorities, at county or provincial level, have approved at least one of two declarations that appear to reject demands advanced under the banner of LGBT rights.

But in a reminder that attitudes to LGBT rights are also shaped by an urban-provincial divide, the city councils have rejected the declarations. The discrepancy means that many gay residents of the region are, like Schrodinger’s Cat, in an indeterminate state: simultaneously within, and not within, an “LGBT-free zone”.

“There is no LGBT-free zone here,” said Milosz Zawistowski, during a meeting at a cafe in Lublin last summer. Stylishly dressed with black-rimmed glasses, he would look at home in gay Berlin or Barcelona. “The fact that some nonsense is spreading through local towns and villages makes no difference to me,” he shrugged.

The declarations that underpin the “LGBT-free zones” come in two forms, neither of which have any legislative weight. The first is a crudely worded statement rejecting “LGBT ideology”; the second, a more ambiguously worded statement that appears to uphold the notion of the family as an exclusively heterosexual institution. The resolutions endorsing these statements are symbolic, in that they do not alter the legal status of LGBT individuals living anywhere in Poland.

However, Poland’s opposition leaders, LGBT activists and European human rights bodies have argued that these declarations nonetheless constitute a form of discrimination: they discourage local authorities from supporting LGBT rights while encouraging hate speech and violence against LGBT individuals. Law and Justice has downplayed the declarations’ impact. Party leaders and their allies have argued that the declarations cannot be discriminatory because they refer, at most, to an abstraction – “LGBT ideology” rather than people.

Curiously, both sides in this debate have been accused of waging a kind of proxy war on each other’s fundamental rights and values – by cynically mis-labelling them. The government’s opponents say “LGBT ideology” is a made-up phenomenon, a proxy for the real target, which are the rights claimed by LGBT people. “There is no such thing as LGBT ideology,” the prominent Polish centre-left MEP Robert Biedron told the TVN Channel. “If there is anything, it would be an ideology of hate by Law and Justice.”

The government and its allies have meanwhile said the “LGBT-free zones” are an invention, a proxy for undermining what they hold to be the rights of traditional, conservative families. “There are NO LGBT-free zones” in Poland!” tweeted the Polish Minister for Science and Education, Przemysław Czarnek, last September [2020, ed.], in response to Biden’s tweet. The country’s prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, has also described the zones as a “hoax” by LGBT activists.

Law and Justice has done more than any party in the EU to bring homophobic bigotry into the mainstream. However, as the pre-eminent marker of that bigotry, the “LGBT-free zones” are not the party’s creation alone. That label has indeed also been created by the party’s opponents in parliament and the press, and by LGBT activists. As such, it says more about Poland’s political landscape than it does about realities on the ground.

Riot police protect participants at an Equality March in the eastern Polish city of Białystok in July 2019. Far-right protesters clashed with police at marches in Białystok and Lublin in 2019. Photo: Jerzy Baliski / AFP / picturedesk.com

This story examines the complex impact of the “LGBT-free zones” in Poland, two years after they effectively came into being [in 2019, ed.]. It is a story about the political uses of homophobia, and the power of labels in a culture war.

Absence of data

Hostility towards LGBT rights has been a consistent theme within the Law and Justice party’s rhetoric, typically couched alongside opposition to abortion and support for conservative Catholic family values. This rhetoric has intensified over the last two years [since 2019, ed.], coinciding with three election campaigns – parliamentary, European and presidential – where the party was challenged by a resurgent opposition, the liberal centre-right Civic Platform, and by smaller far-right formations.

Over this period, party leaders and their allies in the church have variously compared the campaign for LGBT rights to the plague, Nazism and communism. Science and Education Minister Przemysław Czarnek has gone further than many of his colleagues, describing LGBT people as abnormal and unworthy of equal rights.

Law and Justice has forged its base in small towns and villages, particularly in the poorer east, by casting the state as protector and benefactor for the vulnerable and the overlooked. The party has launched generous welfare programmes targeting the elderly and families, while claiming to guard the country against apparent threats from abroad. It came to power in 2015 with a campaign that claimed the European Union was planning to flood Poland with migrants from war-torn Muslim countries.

Its core constituency is a sizeable one – the millions of Poles who consider themselves to be conservatives and traditionalists. Many believe they have been neglected by a liberal, metropolitan elite – particularly since the country joined the European Union. The party’s programme is a blend of statism, nationalism, populism and Euro-scepticism.

It is impossible to establish the degree to which homophobia has helped the party hold onto power in the recent elections. A recent survey [2021, ed.] of popular attitudes to gay and lesbian people portray a divided nation. There has been a slow but steady increase in the acceptance of homosexuality over the last 15 years. But roughly two out of three Poles still believe same-sex couples should not show their way of life in public or have the right to marry, and more than four out of five believe they should not have the right to start a family.

The survey, conducted by CBOS, a reputable Warsaw-based polling agency, also indicated that while overall attitudes towards same-sex relationships had become more tolerant over the past 15 years, this trend had slowed towards the end of the last decade. And yet the survey also showed that a majority of Poles – three out of five – did not consider themselves hostile towards gays and lesbians, expressing attitudes ranging from indifferent to overwhelmingly positive.

The Law and Justice party’s candidate in the 2020 presidential election, Andrzej Duda, campaigned on a pledge to defend children from “LGBT ideology”. Photo: AGENCJA GAZETA / REUTERS / picturedesk.com

Poland decriminalised homosexuality in 1932, becoming one of the first countries in the world to do so. Popular attitudes towards openly gay and lesbian people have, however, been heavily shaped by the powerful Catholic church, which has been fiercely critical of non-heterosexual relationships.

In the 30 years since the collapse of communism, the clergy have taken a more assertive role in public life. Over the same period, Poland’s integration into the European Union has exposed the country to new international norms and demands for the equal treatment of sexual minorities. An increasingly visible campaign for LGBT rights has coalesced around calls for the legal recognition of same-sex unions and for sex education in schools to include discussion of discrimination and non-heterosexual relationships.

The declarations adopted by local governments are widely interpreted as a rejection of these demands. The impact of these declarations on LGBT life lies at the heart of the debate over the zones.

There is anecdotal evidence of an uptick in homophobic aggression since the declarations were passed, with violent counter-protests accompanying the Equality Marches in Lublin and Białystok in 2019. However, it is impossible to establish the extent to which this violence is a direct result of the declarations versus, for instance, the broader climate of hostility to LGBT people fostered by the government. There are no official data on homophobic attacks as Polish law does not recognise these crimes as a distinct category.

Milosz Zawistowski has glimpsed the face of homophobia in his city. Three years ago [2018, ed.], he went with his mother to Lublin’s first Equality March – the Polish version of Pride – only to be hemmed in by rioting football hooligans and far-right protesters. The police eventually secured the route, making some 20 arrests, and the parade went ahead.

He would march again the following year [2019, ed.], after the region had earned the “LGBT-free zone” label. This time, the route of the parade seemed better secured, and the hooligans were kept well at bay by riot police. But the danger was arguably greater. Among the dozens of rioters arrested that day were a married couple, carrying a rucksack full of firecrackers taped to cans of lighter fluid – crude, homemade explosive devices.

The couple was in their twenties, the man was a gas-fitter by trade, the woman unemployed. At their trial, experts testified that the explosives, although crude, could have been deadly if deployed as intended, against the marchers. The male defendant offered an explanation for his actions: “I am for Poles and for family. For me, family values are a boy and girl.”

Milosz told BIRN that he had not ruled out relocating to Warsaw. He added, however, that if he were to ever make the move, it would have nothing to do with his sexuality. “My orientation neither helps nor hinders me here,” he said. “I am not fighting for anything but nor am I hiding very much.” Warsaw appeals to him as it appeals to the youth of provincial cities all over Poland – it has a thriving job market. “I am sick of standing behind the bar,” he said. “And there is simply no other job here for someone like me.”

Haphazard process

The term, “LGBT-free zone”, entered Polish political discourse as a crass marketing stunt. In July 2019, the slogan was featured on a free sticker given away with the weekly edition of Gazeta Polska, a pro-government tabloid known for its ultra-conservative, nationalist stance. The illustration on the stickers featured the colours of the rainbow crossed out – an apparent riposte to the rainbow-flag stickers commonly displayed by LGBT-friendly venues. The sticker campaign provoked an outcry and was swiftly banned in a lawsuit brought by an LGBT activist, Bart Staszewski. Gazeta Polska responded to the lawsuit with a fresh sticker campaign bearing a new slogan: “LGBT-ideology free zone”.

The slogan, “LGBT-free zone”, gained notoriety after being featured on stickers given away by a right-wing Polish tabloid, Gazeta Polska. Photo: Matinee71 / Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, the original slogan would assume a life of its own, appropriated by the government’s opponents. Among liberal politicians and the press, the “LGBT-free zones” label would be used to describe a new trend sweeping through local governments in the south-east: the approval of the two types of declaration deemed critical of LGBT rights.

The first of these declarations was a rambling text, peppered with non sequiturs, declaring its opposition to a variety of phenomena from “homo-propaganda” and “political correctness” to the “sexualisation of children”. The apparent source of these ills lay in something described in the manner of the political programme of a mysterious organisation: “LGBT ideology”.

The second text, commonly known as the “family charter”, did not refer to LGBT rights at all. Instead, it encouraged local governments to promote a traditional view of the family, and to withhold funds from NGOs that opposed this. The votes on these declarations were held in seemingly haphazard fashion, at every level of local government across municipal, county and provincial council meetings in the south-east, wherever Law and Justice had a majority.

This process did not merely generate inconsistencies, as with cities such as Lublin being left both within and outside the zone. It also generated duplication, with smaller towns such as Kraśnik and Świdnik seemingly adopting the same declaration three times – at municipal, county and provincial levels. According to an opposition politician from Świdnik, the symbolic resolutions were an electioneering tactic, geared to generating press coverage.

“Each such vote, while not changing much in reality, leads to a mention in the local press, some publicity, some attention,” Jakub Osina, of the Świdnik Common Cause, told BIRN. “It ‘sells’ much better than the daily decisions by local authorities, it allows you to gather your allies around you. There is no better way of conquering the opinion polls before an election.”

Nazi comparisons

Though they did not say so explicitly, the declarations were widely interpreted as a response to measures taken by the liberal centre-right Civic Platform, the main opposition grouping challenging Law and Justice in the polls.

In February 2019, the opposition-controlled city of Warsaw had approved a pledge committing itself to a more inclusive policy towards sexual minorities. The pledge, known as the LGBT Plus Charter, listed a series of measures to tackle prejudice and discrimination in areas such as secondary education. It was spearheaded by the mayor of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski, a leading light in Civic Platform who would eventually become the coalition’s candidate in the 2020 presidential elections.

The mayor of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski, facing the crowd in the picture, was the main opposition challenger to the Law and Justice party in the 2020 presidential election. Photo: Newspix / EXPA / picturedesk.com

On March 26 2019, six weeks after Warsaw approved the LGBT Plus Charter, the Law and Justice-controlled town of Świdnik, on the outskirts of Lublin city, became the first place in Poland to adopt a declaration rejecting “LGBT ideology”. On the same day as the vote, a fundamentalist Catholic newspaper sympathetic to the government, Nasz Dziennik, published the full text of the declaration alongside a column calling for the need to fight “moral scandalisers”.

The newspaper, which has a nationwide circulation, presented the declaration in the manner of a petition, with a blank space where readers were encouraged to write the names of their own towns, villages, and cities. Throughout the year’s European and parliamentary elections, successive local governments in the south-east would seemingly do the newspaper’s bidding, passing declarations viewed as hostile to LGBT rights.

The left-liberal weekly, Polityka, was among the first outlets to link this trend in local government to the slogan on the sticker given away by Gazeta Polska, a publication at the opposite end of the political spectrum. On 31 July 2019, the headline for a column in Polityka would imply that the declarations approved by local governments were, in effect, creating “LGBT-free zones”.

The label stuck. Amid growing indignation over the anti-gay rhetoric adopted by Law and Justice leaders on the campaign trail, opposition politicians and the liberal press began referring to municipalities across south-eastern Poland as “LGBT-free zones”.

The label also prompted comparisons with the “Judenfrei” or “Judenrein” zones, the words used by Poland’s Nazi occupiers to refer to areas where they had systematically expelled and murdered the Jewish population. “German fascists created Jew-free zones,” tweeted the deputy mayor of Warsaw, Paweł Rabiej, in July 2019. “As you can see,” he added, “this tradition finds worthy followers” within Poland’s clergy and ruling party.

In the second half of 2019, the label entered mainstream EU politics. That November, the European Parliament held a debate on “public discrimination and hate speech against LGBT people, including LGBT-free zones”, marking an early usage of the term by an international political body.

A screengrab from the website of the left-liberal Polish weekly, Polityka, showing the headline for an article linking “LGBT-free zones” to the local government declarations.

During the session, an argument broke out over the extent to which parts of Poland could be termed a no-go zone for its gay citizens. The centre-left MEP Robert Biedron, the country’s first openly homosexual politician, told the parliament: “I am a Pole and in 2019, there are places in my homeland, in the heart of Europe, where I cannot go. There are shops, restaurants and hotels that I cannot enter.”

He was challenged by Law and Justice MEPs, who asked him to name the venues that had barred him. Biedron responded with a single example – a restaurant in the city of Krakow whose decision to display one of Gazeta Polska’s stickers had been featured in a recent report by the liberal Warsaw newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza. The owner of the restaurant would go on to remove the sticker, reportedly saying that he merely opposed “leftist ideology” and had never discriminated against anyone.

In December 2019, the European Parliament held a vote on the debate. A majority of MEPs backed a resolution condemning all “public acts of discrimination against LGBTI people, notably the development of so-called ‘LGBTI-free zones’ in Poland”.

‘Deep fake’

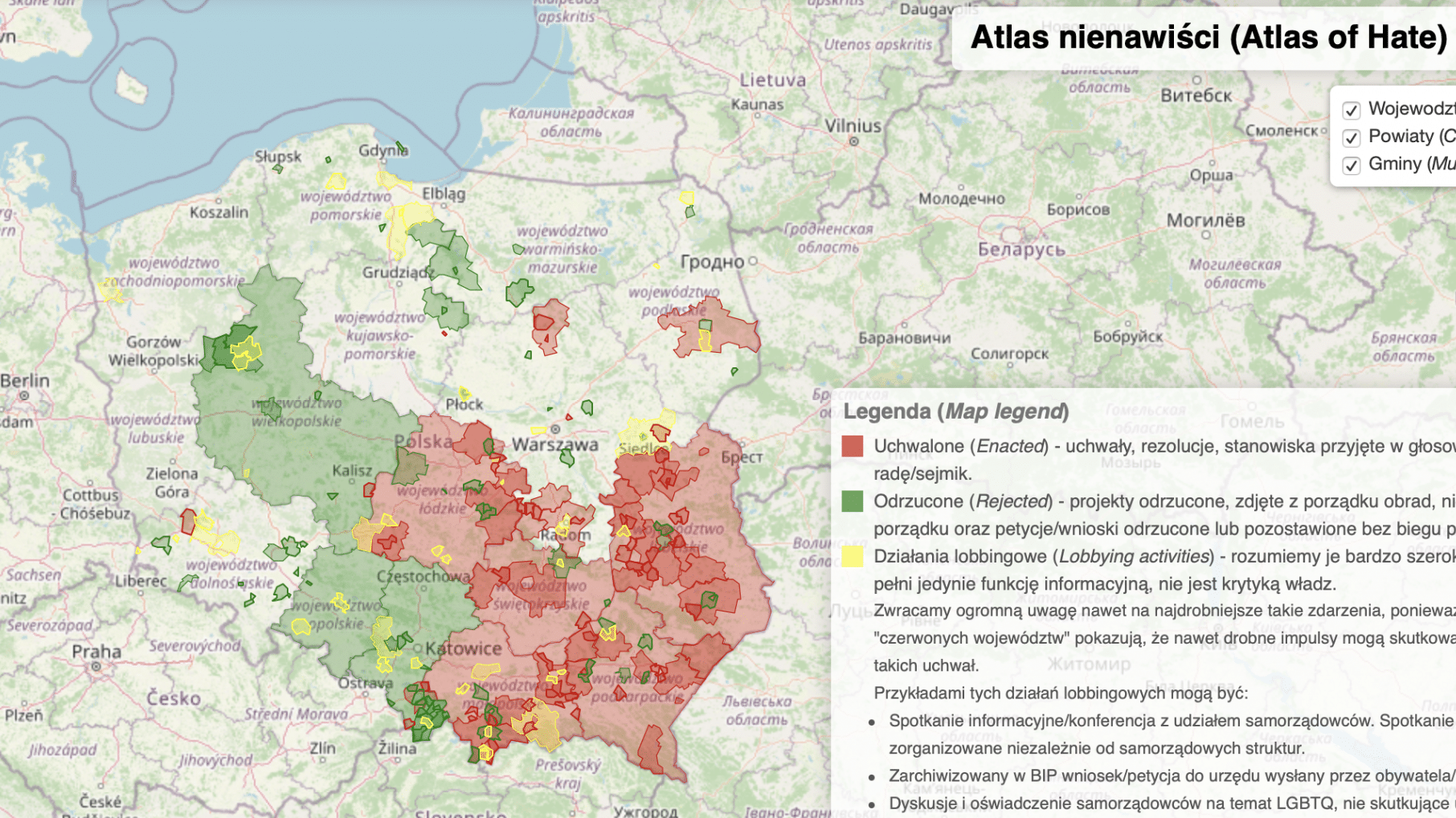

By the end of 2019, nearly 100 local government authorities had approved at least one of the two declarations rejecting LGBT rights. The areas governed by these authorities spanned roughly a third of the country – a fact that would be highlighted in an online map, entitled the Atlas of Hate, published by LGBT activists and heavily cited in the press.

Throughout 2020, activists would keep the “LGBT-free zones” in the public eye through social media campaigns that tethered the label to specific parts of Poland. In January 2020, Bart Staszewski, the activist who had successfully sued Gazeta Polska over its sticker stunt, launched an online project featuring photographs from areas that had adopted the controversial declarations.

The images depicted gay, lesbian and transgender residents of the area posing in front of highway signs. As well as the usual place names, the signposts carried an additional placard bearing the slogan, “LGBT-free zone”. The phrase appeared in four languages – Polish, English, French and Russian – in sober black lettering on a yellow background, mimicking the look of roadside hazard warnings.

Staszewski had created and installed the additional signs himself – but on the internet, many took them to be official. His posts went viral, and the photographs of doctored road-signs became a fixture in news stories about the region. The Law and Justice Party reacted with fury. Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said Staszewski’s campaign had “completely falsified” the reality about Poland. “To call it fake news would not do it justice,” he said, in October 2020. “It was a deep fake.”

The “LGBT-free zone” road-sign project, using images similar to this one, has attracted the ire of the Law and Justice party. Photo: Bartosz Staszewski / Wikimedia Commons

Piotr Skrzypczak, one of the founders of Homo Faber, a Lublin-based human rights organisation, told BIRN that he too was initially fooled by Staszewski’s campaign. “When I first saw those photos, I jumped up in search of pliers and a hammer to take down those signs,” he said. “It took me a minute to understand that it was a provocation.”

Skrzypczak wondered how many Poles still believed that officials in the east had “allowed something like this to be hung at the entrance to the city”. Regardless, he said, the images were a suitable response to the local government declarations. “Bart Staszewski’s gesture seemed very appropriate to me. It showed us where we had found ourselves.”

‘Dog whistle messaging’

How appropriate is the “LGBT-free zones” label? This question would form the crux of court cases brought against the activists by local authorities that had approved the declarations. Staszewski was sued by municipalities in the south-east that said his photographs of doctored road-signs falsely implied that LGBT people were being discriminated against. Legal action was launched on similar grounds against Jakub Gawron, an LGBT activist from Rzeszów who had helped create the Atlas of Hate online map.

Gawron has defended his project as a response to the “symbolic exclusion of non-heteronormative people from the public space”. Staszewski has used similar language to defend his photo project, telling the Polish left-wing magazine Krytyka Polityczna that it was “a symbolic response to the symbolic resolutions” passed by the municipalities.

The government and its allies have also emphasised the symbolic nature of the declarations – as a defence against the charge of discrimination. Moreover, they say, the text of the declarations does not concern LGBT people, as it refers only to “LGBT ideology” rather than to individuals.

An official from Ordo Iuris, the ultra-conservative Warsaw think tank responsible for the “family charter”, described the initiative as a “soft” measure to promote a “pro-family” culture. Pawel Kwasniak, the co-ordinator for the charter, said the document was a response to a growing worldwide threat posed by “far-left ideology, social movements, the LGBT ideology and gender ideology”.

However, critics of the declarations tend to be sceptical of terms such as “LGBT ideology” and “pro-family”. They argue that such ambiguous language functions as a classic “dog whistle”. On the one hand, it signals to the Law and Justice party’s natural constituency, the conservatives and nationalists of Polish society, that homophobic attitudes are acceptable. On the other hand, it allows the party’s leaders to deflect accusations of outright homophobia.

A screengrab showing the Atlas of Hate, an online map project by LGBT activists that depicts the areas where local governments have approved one of the two declarations.

The co-author of a recent report on homophobia by the European human rights watchdog, the Council of Europe, said discussions with Polish authorities often ended up circling around hazy notions of family and ideology. “It’s quite interesting that as we went deeper into these arguments, the attacks on LGBT people used terminology that cannot be defined,” co-rapporteur Andrew Boff told BIRN. “If you want to oppose an ideology, you have to say what that ideology is, and at no point do they define what LGBT ideology is.”

Boff said the declarations by local authorities in the south-east had used language that “skirted around the law”. It had allowed the Law and Justice party’s supporters to reach their own conclusions about the declarations’ underlying sentiments while its leaders could keep saying that they had “no effect whatsoever on the lives of LGBT people”.

In this context of “dog whistle” messaging by the government, Boff said he could see why activists had come up with the “LGBT-free zone” label – even if such zones did not technically exist. “There is nothing specifically that is a gay-free zone,” he told BIRN. But it was understandable, he added, that “activists who are trying to defend the rights of LGBT people” had defined them as such. He cautioned, however, against literal interpretations of the term. “What you can say is that in those zones, LGBT people are made to feel desperately unwelcome. That’s much closer to the truth than saying they are LGBT-free zones.”

The LGBT activists have told BIRN that their work accurately reflects the situation on the ground. Bart Staszewski said in an email that he viewed the zones as “real areas of discrimination”. The declarations, he said, had led to a “chilling effect” by exposing municipal bodies to the threat of financial reprisal if they were deemed to support LGBT rights. “For LGBT people, this is a clear signal that they will face difficulties in, for example, organising an Equality March.”

Jakub Gawron told BIRN that the title, Atlas of Hate, had seemed “quite mild” when it was proposed as a name for the online map depicting the areas that had adopted the declarations. “We have to remember the social and political context in which those declarations were adopted,” he said, citing the government’s homophobic rhetoric during successive election campaigns over the past three years, as well as “near-daily attacks on the LGBTQ community” by the state broadcaster, TVP. “And of course, we cannot forget the attempted pogrom in Białystok and the attempted bombing in Lublin,” he said, referring to the violence that accompanied the Equality Marches in both cities in 2019.

‘Chilling effect’

Had the declarations in fact breached the law? This question would form the basis of further court cases – these ones mounted against the local authorities by an independent state body, the office of Poland’s Commissioner for Human Rights, or Ombudsman. Lawsuits brought by the office of the ombudsman, Adam Bodnar, have asked regional courts across Poland to consider whether certain local authorities had violated the constitution by approving the declarations.

Police protect a EuroPride March in Warsaw in 2010. Hostility to LGBT rights continues to provide a rallying point for the Polish far right. Photo: Leszek Szymanski / EPA / picturedesk.com

Anna Błaszczak-Banasiak, the director of the body’s Equal Rights Team, said the legal challenge was far from straightforward. “We went to court because of the obstinacy of the ombudsman himself, who kept saying, ‘find a way’,” she told BIRN. The way proved to lie through technicalities, as well as through the field of human rights. When some of the municipalities were eventually sanctioned, it was rather in the manner of Al Capone – jailed for tax evasion instead of the murders.

In July 2020, two provincial courts issued the first rulings in the Ombudsman’s favour. The local authorities in question were found to have been treading on the toes of central government by passing resolutions that might, for instance, have an impact on educational policy. “We proved the communes went beyond their competence and violated the constitution by creating normative acts, such as guidelines for subordinate entities, including schools,” explains Błaszczak-Banasiak. “Discrimination was something of a side-dish here.”

The ombudsman’s lawyers also managed to prove that the declarations had created a “chilling effect” by preventing or deterring public servants from acting in support of LGBT people, as residents, potential employees or contractors.

However, some local politicians question whether the declarations could have made discrimination any worse in small towns and villages where officials’ attitudes have long been determined by partisan loyalty. “Chilling effect in Świdnik?” asked opposition councillor Jakub Osina, of the town that he represents in Lublin province. “But who would be ‘frozen’ out? All of the officials of these communes take their cue from other, no one will step out of line there. These people know perfectly well where the red lines are.”

Former Polish Prime Minister Beata Szydlo greets workers at a factory in the town of Świdnik, outside Lublin. The Law and Justice party draws much of its support from the surrounding south-eastern region. Photo: P. Tracz / Kancelaria Prezesa Rady Ministrów

Michał Widomski, a former Law and Justice councillor in Lublin city, said the acceptance of LGBT people in the provincial south-east may indeed be subject to a pernicious “chilling effect” – but this was not the result of the declarations alone. Instead, he argued, it was a much bigger phenomenon – the urban migration of LGBT people, along with other youth from the provinces – that meant discriminatory attitudes were less likely to be challenged.

A self-confessed homophobe in his youth, Widomski demonstrated in support of LGBT rights at Lublin’s first Equality March. He credits a high school friend, who came out as gay in his thirties after leaving Lublin, with having shifted his attitude. “It was only then that I realised what all this homosexuality is, I didn’t know anyone like that before,” he told BIRN. “So, the only chilling effect in those towns and villages, I imagine, is the departure of all those people who could tell others about themselves and teach them something, as my friend did for me.”

‘Raging desert of LGBT ideology’

Local government debates from the south-east, broadcast online, offered a window into how the declarations were being interpreted on the ground. In the town of Kraśnik, the deputy chairman of the Law-and-Justice controlled district council became tongue-tied when asked to spell out what the “LGBT” acronym stood for. Lost for words, he launched into a claim that children were being taught to masturbate under the World Health Organisation’s anti-discrimination guidelines for schools, recycling the basis for an unfounded conspiracy theory promoted by the party’s supporters.

While expressions of hostility to “LGBT ideology” were common at council meetings, the bizarre Kraśnik speech prompted a backlash. Cezary Nieradko, a 21-year-old nursing student from the town, began petitioning municipal authorities to revoke the declarations and sign up to the main principles of Warsaw’s LGBT Plus Charter.

His campaign uncovered a mixed picture of attitudes towards sexual minorities in small-town Poland. Over the course of the summer [2020, ed.], he amassed enough signatures from the town’s residents to bring the matter to a vote in the council. “There were no homophobic attacks, though some people refused to sign and others said they were afraid of losing their jobs,” he told BIRN.

A religious procession in the town of Kraśnik, south-eastern Poland. The influence of the Catholic faith is particularly strong in small towns and villages. Photo: Episkopat News

Nieradko said he had been motivated to become an activist, in part, by the hostility he had encountered when he had disclosed his sexual orientation to a teacher. After going public with his sexuality in the course of his activism, he said he had received occasional verbal abuse on the street, as well as congratulations and expressions of gratitude from “a dozen or so strangers”.

“First, there is verbal aggression, then violence, and finally the victims of discrimination are sent to the gas chambers.”

His motion was eventually defeated, falling two votes short, at a Kraśnik district council meeting in September 2020. The colourful language of the debate made it an unlikely hit on the internet. “We cannot abandon Catholicism for the raging desert of LGBT ideology,” cried a Law and Justice councillor. An MP from the opposition Civic Platform, attending as an observer, commented: “First, there is verbal aggression, then violence, and finally the victims of discrimination are sent to the gas chambers.”

‘Pogrom atmosphere’

Several politicians and commentators critical of the “LGBT-free zones” have drawn parallels with the fate of Poland’s Jews, and with specific terms such as “Judenfrei” and “Judenrein” that were used by Nazi occupiers to describe areas where the Jewish population had been expelled or murdered.

The historic parallels are also implicit in e-mails sent to the Ombudsman’s office, testifying to the fears of LGBT people in Poland. “If we carry on like this, the ruling party will try to lock us in cages,” reads one message, shared by the Ombudsman. “It is as if they were preaching the creation of an Aryan race in Europe, the only ones that are allowed to live here,” reads another message.

Terms such as “Judenfrei” have a particular resonance for Lublin. In 1939, roughly a third of the city’s 122,000 inhabitants were Jews. Its status as a major centre of Jewish life reflected that of Poland as a whole, home for centuries to Europe’s largest Jewish population. Before the Second World War, roughly one in ten Polish citizens – or some three million people – were Jewish. Under the Nazi occupation, Lublin would become a logistics hub for the Holocaust. It was from here that the Nazis managed Operation Reinhard, the codename for their plan to murder some two million Jews from the Polish territory under their control.

The interior of a derelict synagogue in the town of Kraśnik, south-eastern Poland. The region used to be a major centre of Jewish life in Europe. Photo: Emmanuel Dyan / Wikimedia Commons

Jews from other parts of Europe were also deported to the Lublin region, where the Nazis had built the infrastructure for the final and deadliest phase of their genocide. In the early 1940s, a network of death camps in the area was used to kill some 1.7 million people – the majority of them Jews, as well as an unknown number of Roma, Poles and Soviet prisoners of war.

Anna Dabrowska, a co-founder of Lublin-based human rights group, the Homo Faber Association, said it was risky to compare the historic treatment of the Jews with the contemporary treatment of sexual minorities. “Making associations between the Holocaust and the current situation of LGBT people in Poland seems to me a bad idea, even if I understand the intentions,” she told BIRN. “This type of metaphor not only takes us away from understanding the nature of the Holocaust, but it also promotes fear…. It makes it sound like we are dealing with a pogrom atmosphere. Historically speaking, this comparison is utterly wrong.”

However, Dabrowska said, the wartime fate of the Jews and other minorities nonetheless held a clue to understanding the roots of contemporary homophobia in the south-east. “These are communities racked by trauma,” she said. “These people remember how their Jewish neighbours were dragged to the cemetery by the Germans. Everyone saw it, everyone heard it.”

“It is not just a phobia related to gays, lesbians or anything else hidden under the letters of an acronym. It is a phobia of different identities.”

A region that had entered the war as a melting pot emerged as a homogenous society. The post-war population, now overwhelmingly Catholic and Polish-speaking, was left with a vague fear of diversity in all its forms, Dabrowska told BIRN. “It is not just a phobia related to gays, lesbians or anything else hidden under the letters of an acronym,” she said. “It is a phobia of different identities.”

Dabrowska’s colleague at Homo Faber, Piotr Skrzypczak, believes events in the recent have further contributed to this distrust of diversity, pointing to the manner in which the country entered the European Union – with minimal soul-searching or debate. “We joined the European Union, this great multicultural melting pot, in 2004, without discussing why we are changing our laws,” he said. “And now we are surprised that we have this great backlash.”

Fitful progress

Although the “LGBT-free zones” have damaged Poland’s image in the EU, their fate will most likely be decided at home – by the Supreme Administrative Court. The court is currently [2021, ed.] reviewing appeals brought by local authorities that lost their cases to the Ombudsman.

If the court rejects the appeals, the declarations will be deemed unlawful and the basis for the “LGBT-free zones” will effectively collapse. However, if the court overturns the previous decisions, the declarations will stand and the Ombudsman’s campaign against them will be derailed. The Supreme Administrative Court is seen as a relatively independent body, having largely escaped Law and Justice’s efforts to tighten its grip on the Polish judicial system.

The Equality Marches continue to boost the visibility of LGBT people in Poland. In cities such as Warsaw, the annual parade has become something of a tradition. Photo: Jakub Kaminski / EPA / picturedesk.com

Locked in confrontation with state-sponsored homophobia, the struggle for LGBT rights has made scant progress through the traditional method, of getting state institutions to enact laws against discrimination. Two years after it was approved, Warsaw Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski’s LGBT Plus Charter, the apparent trigger for the declarations, has barely been implemented.

Last September, LGBT activists from the NGO, Love Does Not Exclude, said only one of the charter’s ten key pledges had been fulfilled – the mayor had officially become patron of the city’s annual Equality March. This year, the city took the first steps towards fulfilling a second provision – the creation of a refuge for LGBT people in insecure or unsafe accommodation.

To date, the charter’s most discussed provision – for tackling discrimination through school sex education lessons – has not been rolled out. City officials said they had taken initial steps towards implementation, but had been slowed down by the coronavirus pandemic. However, a spokeswoman for Love Does Not Exclude said the city appeared to be “scared of the subject”.

Most of the remaining provisions are a long way from being implemented, and a few have been scrapped altogether. Like the hostile declarations that it inspired across the south-east, the charter that was billed as a landmark in the struggle for LGBT rights remains, for the time being, a largely symbolic document.

First published on 15 April 2021 on Reportingdemocracy.org, a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.

This text is protected by copyright: © Jakub Janiszewski / Reporting Democracy. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team. This article was edited by Neil Arun. It was produced as part of the Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation, in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations or on top of the article. Cover picture: Illustration: Sanja Pantic / BIRN

Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence

Since 2007, this fellowship programme has been providing financial and editorial support to journalists who have good ideas for cross-border reports. Tutors support the writing process to enhance the journalistic skills and knowledge of the fellows.

Each year, a jury selects ten experienced journalists from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Serbia and Slovakia. The three best articles are awarded a prize at the end and – along with the other articles – published in numerous high-quality media outlets.

The Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) and ERSTE Foundation set up the Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence programme in 2007 with a mission to encourage professional, in-depth, cross-border reporting in Southeast Europe.