‘Energy independence’ for Croatia

Critics turn up eat on a plan to build a liquid natural gas platform.

Environmentalists and locals decry it. Experts call it a waste of taxpayers’ money. So why is Croatia pressing ahead with a project to turn a top tourist destination into a hub for liquid natural gas?

“Obliti privatorum publica curate,” reads the Latin inscription above the town hall door — “Common good should take priority over private matters.” For Mirela Ahmetović, mayor of the seaside town of Omišalj on the Croatian island of Krk, it is a maxim to live by. When she should be on vacation, she is in the office discussing the energy project she has been fighting these past three years. Ahmetović, 38, does not mince words. She organises her thoughts methodically, like the papers filed in a thick, red binder on the desk in front of her: letters of complaint penned to ministers and state institutions, most of which went unanswered. “As long as I’m the mayor of Omišalj […] I’ll look for every legal way to close down this project,” Ahmetović told BIRN. “This is my job, my duty and my pleasure. I’ll write to the president of the world if I need to.”

The seaside town of Omišalj in the northern Adriatic. Photo: © BIRN

The project she is set against is a floating terminal for liquid natural gas (LNG), to be built on the northwestern tip of Krk, Croatia’s largest island and a top tourist destination. Deemed a “project of strategic interest”, it involves mooring a 280-metre-long repurposed oil tanker in full sight of the ruins of the ancient Roman town of Fulfinum, just off Omišalj. The view overlooks the sparkling Bay of Rijeka in the northern Adriatic. With a price tag of 234 million euros, the terminal will allow vessels ladened with LNG to offload their liquid cargo for on-site conversion to ordinary gas, which can then be distributed via Croatian pipelines. At full capacity, it could process 2.6 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas per year — equivalent to almost 80 per cent of Croatia’s annual gas consumption. It is due to be up and running by 2021.

KRK LNG Terminal. Regasification capacity. Source: International gas union, LNG report for 2019. Infographic: © Sara Salamon

The initiative has received substantial EU funding as one of the bloc’s Projects of Common Interest, key cross-border infrastructure projects that link the energy systems of member states. The government says it is “important for Croatia’s energy independence and security” because it will help diversify gas supply — a polite way of saying Croatia will not have to rely so much on Russia.

Omišalj Mayor Mirela Ahmetović leafs through files in the town hall. Photo: © Jelena Prtorić

But experts, activists and locals interviewed by BIRN see the project as a cautionary tale of what happens when blind adherence to the dogma of energy security trumps common sense. Critics say the government has rammed through the plan without scrutiny or consultation with those who will be affected. They also oppose it on environmental grounds, describing it as a threat to marine life in Krk’s turquoise waters. Then there are doubts about its economic viability. The government has never made public a proper cost-benefit analysis, but BIRN can reveal that Croatia is blundering towards a hulking waste of public money.

Construction of a jetty to connect the future LNG terminal to the shore off the coast of Omišalj. Photo: © BIRN

Less than a year before the terminal is due to start operation, all indicators suggest the project has little hope of breaking even. Nor will it do much to drive down gas prices for Croatian consumers. In fact, experts say Croatian taxpayers will foot the bill for a 100,000-tonne eyesore of dubious value to the country’s energy independence that will mainly benefit other countries in the region.

EU energy orthodoxy

With natural gas deposits in the Adriatic and the eastern Slavonia region, Croatia fares better than many other EU countries in terms of energy independence. “We currently produce enough gas to meet almost half of our needs,” said Katarina Simon, a gas specialist at the University of Zagreb’s Faculty of Mining, Geology and Petroleum Engineering. “But as our national production shrinks, we get more dependent on imports.” Like elsewhere in Europe, Croatia imports gas from Russia — around 2.04 bcm in 2018, or two-thirds of the country’s annual consumption, according to figures from Russian gas giant Gazprom. By comparison, Germany imported 58.5 bcm that same year, making it Gazprom’s single largest buyer in the European Union. Slovakia, whose population is only slightly bigger than Croatia’s, imported 5.8 bcm.

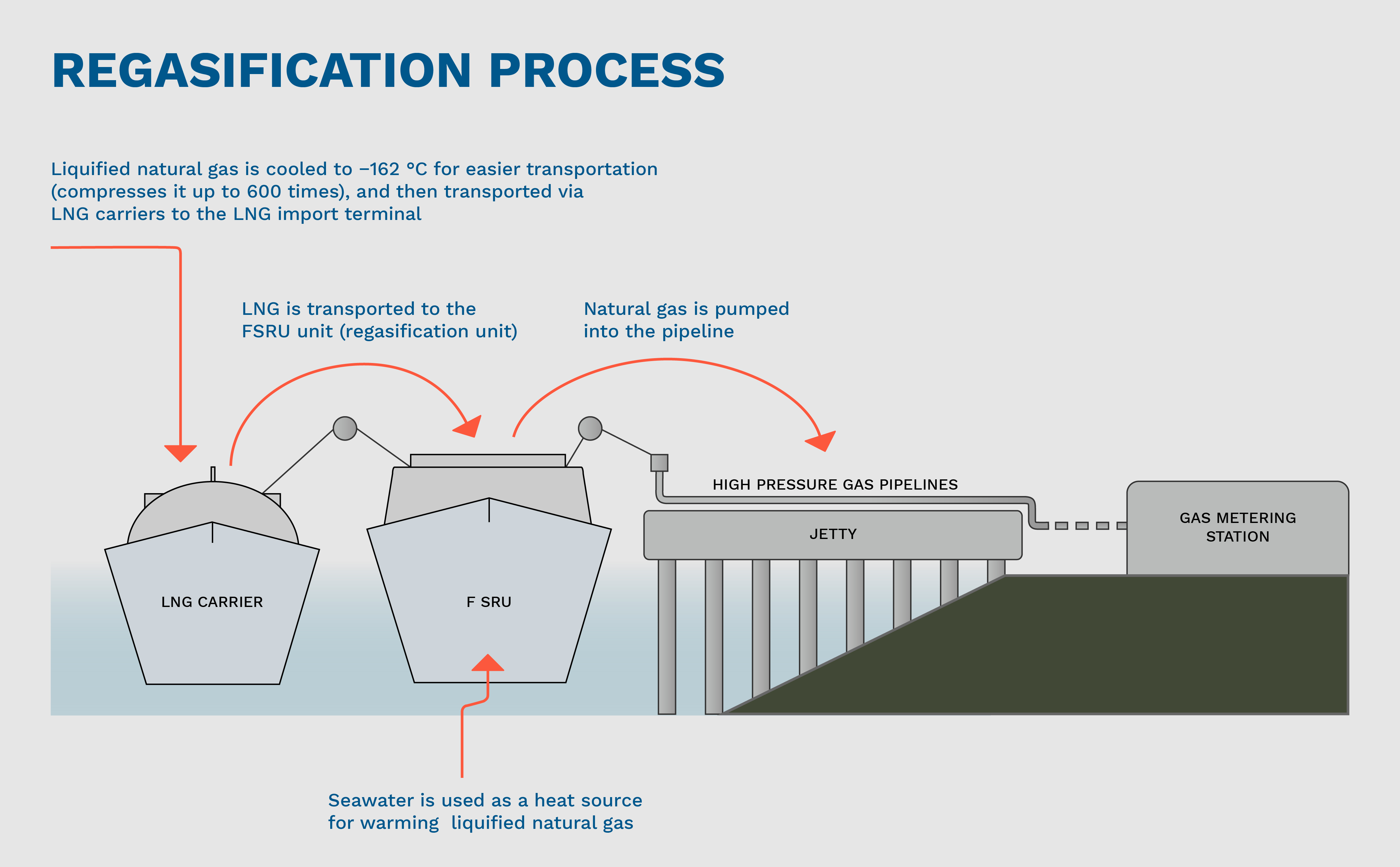

Following a string of Russian-Ukrainian gas disputes that halted gas supplies to Europe in recent decades, the EU started looking for alternative gas sources, and LNG became central to its energy policy. LNG is an acronym that says as much about the transportation method as the gas itself. To minimise the cost of shipping gas over long distances, natural gas gets cooled to minus 162 degrees Celsius, turning it to liquid. This compresses it by up to 600 times. Liquid gas is then transported to LNG import terminals — such as the one planned in Omišalj — where it gets regasified before being pumped into gas pipelines and distributed to consumers.

Regasification process. Infographic: © Sara Salamon

Such LNG import terminals have thus become the new gateways for the non-Russian gas supply to Europe. LNG is also seen as a “transitional fossil fuel”, part of an EU strategy to phase out coal and oil. In 2016, the European Commission unveiled an EU strategy for LNG and gas storage that includes building the necessary infrastructure “to complete creation of the internal energy market and identifying the necessary projects to end the dependency of certain member states on one gas supply source”.

Pascoe Sabido, a researcher at the Corporate Europe Observatory, a Brussels-based non-profit that monitors the effects of corporate lobbying on EU policy, said the push for more LNG infrastructure came from the gas and pipeline industries, as well as the bunkering sector providing LNG to ships for fuel. “This infrastructure is built to last,” he told BIRN in a phone interview. “In 20 years, it will be easier for these companies to slow down the process of the natural gas phase-out with the argument that we have built all this infrastructure and should not abandon it.”

“This infrastructure is built to last. In 20 years, it will be easier for these companies to slow down the process of the natural gas phase-out with the argument that we have built all this infrastructure and should not abandon it.”

In October, the Corporate Europe Observatory teamed up with environmental groups including Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace to publish research showing that since 2010, just five oil and gas giants — Shell, BP, Total, ExxonMobil and Chevron — spent at least 250 million euros on lobbying the EU. The report also notes that the EU, despite its objective of fighting climate change, has been generously subsidising gas infrastructure. “Over 1.6 billion euros has gone on gas projects since 2014 when we know that any additional infrastructure will lock us into a fossil fuel future,” it says.

According to a market study by German energy consultancy Team Consult, as of the end of 2017, total regasification capacity in the EU’s 24 large-scale LNG terminals stood at 146 bcm, compared with 90 bcm in 2007. This figure is expected to grow significantly, with 22 additional large-scale LNG import terminals either planned or under consideration in Europe (17 in EU countries), according to industry body Gas Infrastructure Europe.

This LNG infrastructure boom is warmly welcomed on the other side of the Atlantic, where the United States has become one of the world’s biggest gas exporters. The US Energy Information Administration expects 2019 to be a record-breaking year for natural gas exports. Meeting with US President Donald Trump in 2018, former European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker promised that “Europe would import more gas from the US”.

Mike Fulwood, a senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, said such statements give a misleading picture of how the market works. “Juncker doesn’t buy gas, and Trump doesn’t sell it,” he said in a phone interview. “The market is buying and selling gas.” For Fulwood, one of the main advantages of LNG terminals is the fact they can be used as leverage for bargaining with Russia. “With an alternative gas supply source, it is easier to negotiate down Gazprom’s prices,” he said.

“With an alternative gas supply source, it is easier to negotiate down Gazprom’s prices.”

– Mike Fulwood, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies

But that is not much of an option for Croatia any time soon — terminal or no terminal. In 2017, one of the country’s main gas providers, Prvo plinarsko društvo, signed a 10-year contract with Gazprom locking in the price of a billion cubic metres of gas per year until 2027. “Croatia comes back to Gazprom,” ran a headline in Russian daily Kommersant when the news broke.

‘Bleach in the sea’

LNG Hrvatska (LNG Croatia), the state-owned company in charge of implementing the Krk project, did not respond to BIRN’s interview requests or emailed questions. But critics of the LNG plan say blind adherence to EU energy strategy has made it easy for the government to ignore issues that would have doomed other infrastructure projects. Vjeran Piršić, president of the Krk-based Eko Kvarner environmental NGO, is one of the terminal’s more vocal opponents.

Vjeran Piršić with his wife Marijana in their living room/office in Njivice, Krk. Photo: © Jelena Prtorić

Piršić is a burly man with a soft-spoken demeanor. When his cell phone rings, it emits the soothing song of the Eurasian golden oriole, a bird that thrives in these parts. On the windowsill of his home office in Njivice, a village just south of Omišalj, he keeps three Japanese swords. Piršić showed how he holds the swords during meditation, releasing tension when campaigning gets stressful. He has successfully fought oil drilling in the Adriatic, coal production in the Croatian peninsula of Istria and a project to extend a Russian oil pipeline to the Adriatic. These days, he is most concerned with the LNG terminal’s impact on the local environment.

In November 2017, LNG Croatia co-hosted a public presentation in Omišalj with EKONERG, the firm that did the environmental impact study required by law. Around 400 locals from a municipality of 2,500 people attended the event, which included a question-and-answer session lasting almost five hours. In an audio recording of the Q&A, managers are heard giving confused, incoherent answers as the increasingly hostile crowd voices their concerns.

At one point, a local man who introduces himself as Branko Ban starts asking about pollution from sodium hypochlorite used to clean industrial components. The EKONERG experts try to change the topic but Ban has done his sums based on figures in the impact report. Noting that sodium hypochlorite is basically bleach, he declares: “You’ll release about 376,000 kilos of bleach into the sea every year!” The executives on the recording do not deny it, though a year later, in November 2018, LNG Croatia said on its website that the LNG carrier it had purchased would use “mechanical cleaning” rather than hypochlorite to clean industrial components.

“You’ll release about 376,000 kilos of bleach into the sea every year!”

For Piršić, the entire presentation was a “debacle” for LNG Croatia. He said the company failed to allay local worries, including the negative impact on tourism, dangers to sea life and risks associated with the terminal’s exposure to the region’s famously strong winds. The EU energy commissioner’s team told BIRN in an email that “all large-scale infrastructure projects should be developed in close cooperation with local authorities and citizens living close to a project”. But according to Piršić and Mayor Ahmetović, such cooperation has been sorely lacking. Nor are locals seduced by the prospect of many new jobs, since a terminal of this size is typically run by a crew of only 30-40 people. They will be hired by Golar Power, a Norwegian company that will be in charge of operating and maintaining the terminal.

Meanwhile, Ahmetović claims that Environment and Energy Minister Tomislav Ćorić tried to persuade her not to criticise the project in the media by promising to fund a water infrastructure project in Omišalj — if only she hushed up. Recalling a meeting with Ćorić in November 2017, she told BIRN: “I realised that I was actually being bribed with public money.” Ćorić did not respond to BIRN’s request for an interview or emailed questions. Asked about the allegation, the ministry’s press office declined to “comment on these unfounded claims”.

An aerial view of the LNG terminal construction site. Photo: © BIRN

Ahmetović is a member of the centre-left Social Democratic Party (SDP), the main opposition to the ruling coalition led by the conservative Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) party, of which Ćorić is a member. But she denied that her opposition to the terminal was driven by party politics, noting that regional council members from both the SDP and HDZ voted unanimously against the project in November 2017 (though HDZ councillors abstained during the next debate five months later). In June 2018, parliament approved “Lex LNG”, a law that paved the way for the terminal and ironed out property-rights issues to fast-track its construction.

Too little, too late

Whatever the environmental and transparency concerns, gas industry insiders fear the LNG project will simply turn out to be unsustainable. Daria Karasalihović-Sedlar, a specialist in oil and gas economies at the University of Zagreb’s Department of Petroleum Engineering, said Croatia was too late to the LNG game to be a credible player. “Ten years ago, the market wasn’t as saturated with natural gas,” she said. “We could’ve become a gas hub.”

“Ten years ago, the market wasn’t as saturated with natural gas. We could’ve become a gas hub.”

Not only has the number of LNG projects elsewhere in Europe shot up in recent years, but the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) connecting northern Greece to Italy via Albania should be operational in 2020. TAP is part of the so-called Southern Gas Corridor that promises to bring natural gas from the Caspian region to Europe by way of the Balkans and Central Europe.

The idea of building an LNG terminal in Omišalj dates back to the mid-1990s when Croatian state-run oil company INA first proposed it, but the initial plan never got past the exploratory stage. The concept resurfaced at the beginning of the 2000s with the establishment of Adria LNG, an international consortium of energy firms comprising the German E.ON Ruhrgas, the French Total, the Austrian OMV, the Czech-German RWE and the Slovenian Geoplin. Adria LNG’s plan for a 10 bcm-a-year terminal was aimed at creating a gas hub for the region, to be built in partnership with Dina Petrokemija, a Croatian chemical plant then operating on a promontory off Omišalj.

To regasify LNG, it needs to be heated to a temperature greater than 0 degrees Celsius. Adria LNG wanted to use heated water that was a byproduct of chemical production at Dina Petrokemija. Josip Šepčić, a former research and development specialist at Dina Petrokemija, remembers it as a “serious project”. “Our administration was lagging and the foreign companies lost patience,” he said. In 2010, Adria LNG shut their offices in Zagreb. BIRN reached out to all the companies in the consortium to ask why the project was put on ice, but they declined to comment.

‘Free ride for others’

Using the government’s own figures, BIRN put the business case for the latest terminal project under the microscope. The 233.6-million-euro cost of the LNG terminal includes 159.6 million euros to buy a Norwegian tanker built in 2005 and reconvert it into the Floating Storage and Regasification Unit, as the facility is known. Of the total capital expenditure, the European Union is coughing up 101.4 million euros. The Croatian government will pay 100 million euros from the state budget. In July, the European Commission approved this use of taxpayer money as being “in line with the EU state aid rules” against distorting competition. The remaining 32.2 million euros will come from LNG Croatia’s parent companies: power company HEP and transmission pipe operator Plinacro, both state owned.

Deja Vu?

For many in Croatia, news that Hungary is interested in owning a stake in LNG Croatia feels like a bad case of deja vu.

In 2002, the government started the privatisation of state energy company INA. Within a decade, Hungarian energy group MOL had taken over the firm as its biggest shareholder. As of late 2012, it owned 49 per cent of INA, compared with the Croatian government’s 45 per cent stake. In 2011, Croatia’s anti-corruption office accused former Prime Minister Ivo Sanader of receiving a 10-million-euro bribe from MOL in 2008 to “sell INA”.

Sanader was convicted to eight-and-a-half years in prison, though the verdict was later overturned by the Constitutional Court and a retrial ordered. The retrial kicked off in February 2019 with Mol’s top executive, Zsolt Hernadi, Sanader’s co-defendant in the case, being tried in absentia. On December 30, Sanader was found guilty by a Zagreb court and received a prison sentence of six years, while Hernandi received two years.

The bribe that Sanader allegedly took landed in the bank account of Robert Ježić, a Swiss-Croat entrepreneur and former football club and media owner, according to prosecutors. Ježić had previously purchased the DINA petrochemical plant in Omišalj when he became majority owner of a conglomerate called Dioki d.d. in 2005.

A plan for an onshore LNG terminal in Omišalj developed by the Adria LNG consortium of international energy companies in the 2000s sought to locate the project on Dioki property.

But Dioki went bankrupt in the meantime, and Ježić become a key witness in the trial against Sanader.

‘Free ride for others’

Using the government’s own figures, BIRN put the business case for the latest terminal project under the microscope. The 233.6-million-euro cost of the LNG terminal includes 159.6 million euros to buy a Norwegian tanker built in 2005 and reconvert it into the Floating Storage and Regasification Unit, as the facility is known. Of the total capital expenditure, the European Union is coughing up 101.4 million euros. The Croatian government will pay 100 million euros from the state budget.

In July, the European Commission approved this use of taxpayer money as being “in line with the EU state aid rules” against distorting competition. The remaining 32.2 million euros will come from LNG Croatia’s parent companies: power company HEP and transmission pipe operator Plinacro, both state owned.

To get EU funding, infrastructure projects have to show they will be economically viable. This is done by initiating “Open Season” bidding to determine market interest and identify potential customers. During Open Season, LNG Hrvatska received binding offers from just two buyers. One was state oil and gas group INA and the other was HEP.

Together, they committed to buying 520 million cubic metres of gas per year. That is a far cry from the 1.5 bcm of gas the European Commission said would be needed for the terminal to break even on the investment. Despite the unpromising math, the government decided in early 2019 to fund the project.

Rijeka-based daily Novi list quoted LNG Croatia director Barbara Dorić as saying the “economic test of the terminal was positive” and “the LNG prices would be competitive”, implying that buyers would be drawn to low gas prices and thus make the terminal profitable. But analysts said her confidence may be misplaced.

For one thing, LNG Croatia has no control over the price of gas flowing through the terminal, since contracts are negotiated directly between buyers (companies selling gas to final consumers) and sellers (LNG exporting companies). Because LNG Croatia is essentially a third-party service provider whose role is to regasify LNG bought and sold by others, the only price it can influence is the operation tariff it charges. “No matter how competitive your tariffs are, no company will buy your LNG if they can get cheaper gas through the pipeline,” said the University of Zagreb’s Karasalihović-Sedlar.

The European Commission said in July that based on the “Open Season” bids, “Croatia claims the funding gap would amount to a loss of 193 million euros”. And even if the prospect of buying LNG from exporters worldwide can serve as leverage when negotiating gas prices with Russia, chances are it will not be Croatians who see their gas bills fall, said Fulwood from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. “As the terminal is paid for with public money, the Croatian taxpayers are basically giving a free ride to all the other countries that might benefit from it,” he said.

“As the terminal is paid for with public money, the Croatian taxpayers are basically giving a free ride to all the other countries that might benefit from it.”

Hungary is one such country. In April, the Croatian Minister of Environment and Energy announced that Hungary was interested in purchasing a 25 per cent stake in LNG Croatia (see box). Pal Sagvari, ambassador at large for international energy relations at the Hungarian foreign ministry, told BIRN in a phone interview that negotiations were ongoing.

Clouds roll over Independence, a 294-metre LNG terminal in the Lithuanian port city of Klaipeda. Photo: © Jelena Prtorić

“Hungary has always been interested in the terminal because we are looking to diversify our gas sources,” he said. In 2017, Gazprom supplied seven bcm out of the 10.3 bcm of gas that Hungary consumed that year, according to the Russian gas exporter. With a major gas contract between Hungary and Russia set to expire in 2021, Budapest is hoping to renegotiate terms and prices. “[The Croatian terminal] can be a very helpful negotiation tool for us,” Sagvari said.

Independence, Baltic-style

For a sense of what it is like to have an LNG terminal on your doorstep, look no further than the Baltic port of Klaipeda, Lithuania’s third-largest city. In Klaipeda’s well-kempt centre, flower boxes grace the windows of Nordic-style houses while Soviet-era apartment blocks dominate much of the rest of the city. Moored smack in the middle of Klaipeda’s busy port is Independence, Lithuania’s first and only LNG terminal. Hailing it as an example of a well-planned LNG terminal that has made a real difference to energy independence, experts say the success of Independence reflects a clarity of purpose that is missing from LNG Croatia’s plans.

The terminal was built with almost 450 million euros of taxpayer money, according to the European Commission, which approved the state aid in 2013 on the grounds that it “furthers EU energy goals without unduly distorting competition”. From start to finish, the Independence project was completed in less than four years. That compares with around 15 years of stop-start planning by different actors for a terminal in Omišalj. At 294 metres in length, the purpose-built Floating Storage Regasification Unit, or FSRU, is only slightly larger than the tanker being fitted out for Krk, but it can process up to four bcm of natural gas a year — almost double the Croatian terminal’s capacity.

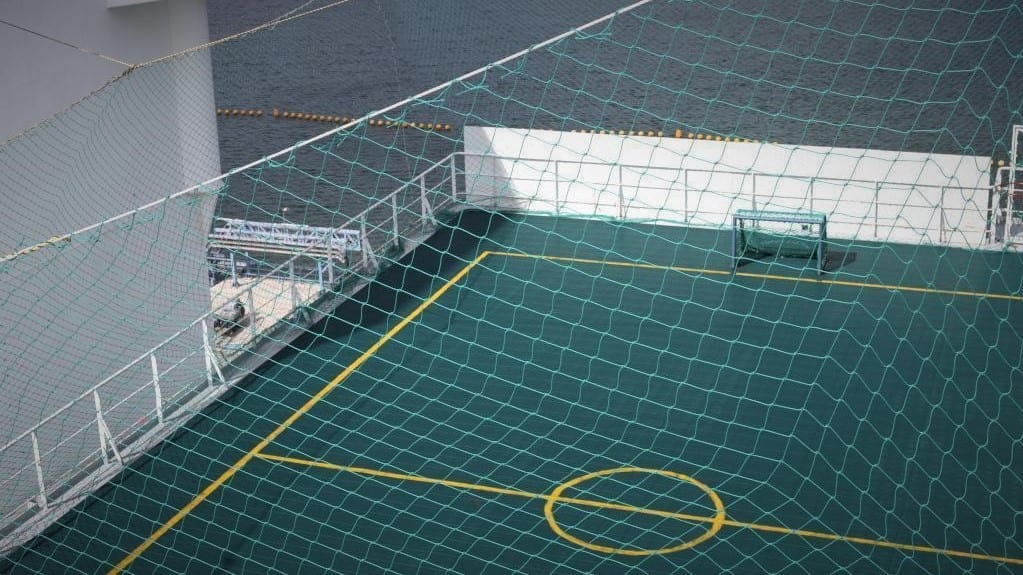

A five-a-side football pitch on the mammoth deck of Independence shows the sheer scale of the LNG terminal in Klaipeda. Members of the 30-strong crew use the pitch to stretch their legs between LNG deliveries. Photo: © Jelena Prtorić

Rytis Savickis, a spokesman for Klaipedos Nafta, the state-owned terminal operator, said that in June alone, Independence regasified enough gas to produce 2.4 terawatt hours of energy — roughly equivalent to the energy consumption that month by Baltic states Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Before Independence started operating in 2014, Lithuania’s population of three million was 100 per cent dependent on Russian gas. There was one pipeline, via Belarus, and one supplier, Gazprom.

By 2018, Lithuania had almost halved its imports of Russian gas, buying 1.4 bcm compared with 2.7 bcm in 2013, before the terminal was built. “[Construction of the terminal] was a political and economic decision,” Lithuanian Foreign Affairs Vice-Minister Albinas Zananavičius told BIRN during an interview in Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital. With its lush plants, low coffee table and white leather chairs, Zananavičius’s office has the air of a living room — save for the Lithuanian flag and presidential portrait on the wall.

Lithuanian Foreign Affairs Vice-minister Albinas Zananavičius sits in his office in Vilnius. Photo: © Jelena Prtorić

“We were paying one of the highest gas prices in the EU,” Zananavičius said. The authorities designated Klaipedos Nafta as the operator and state gas-trading company Litgas (part of state-owned Lithuanian Energy) signed a five-year agreement with Norwegian energy company Statoil (now Equinor) to import 540 million cubic metres of gas annually.

According to Andrius Simkus, an energy lawyer charged with drafting the country’s first LNG legislation in 2010, building infrastructure alone was not enough to break Russia’s monopoly of the gas market. To do that, lawmakers imposed a special contracting obligation for power plants producing heat and electricity and running on gas. “We implemented a legal instrument imposing mandatory procurement of 25 per cent of the gas consumed through the LNG terminal,” Simkus said.

In 2014, right after finishing the terminal, Lithuania was able to renegotiate its Gazprom contracts. Media including Russian state-owned Sputnik reported that Gazprom slashed prices to the country by more than 20 per cent. In the summer of 2016, Croatian President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović visited the Klaipeda terminal. Two framed photos of her hang on a wall in the ship’s conference room, showing her posing with the crew.

Back in Omišalj, locals complain that Grabar-Kitarović has yet to visit the site of the LNG terminal that will redefine their town. During a trip to the island in mid-July, she found time to discuss tourism with the mayor of the city of Krk and meet with local wine, cheese and olive producers. But she steered clear of Omišalj.

The island of Krk plans to become carbon neutral by 2030. Its towns are pioneers in recycling and the use of alternative fuels like solar energy. Locals fear the terminal project will make a mockery of their green aspirations. At the construction site in late autumn, the sound of jackhammers filled the air as dozens of workers poured cement, hoisted concrete pillars and laid steel wires. The jetty that will connect the vessel to the shore was slowly taking shape. In plain sight across the narrow bay, the Roman ruins of Fulfinum — a favourite spot for outdoor classical and jazz concerts when the weather is good — appear to sprout from lawn stretching to a shingle beach. In summer, the bay is popular with locals and tourists who come to swim and relax in the shade of sprawling pines.

An aerial view of the ruins of an early Christian basilica from the 5th Century and the old Roman town of Fulfinum on the edge of Omišalj. Photo: © BIRN

For at least one Omišalj resident, there may be a silver lining to the terminal’s construction. “Maybe it’s an unpopular way of thinking here but Omišalj has for a long time been an industrial town,” said Ivan Leko, a 34-year-old digital marketing specialist whose terrace overlooks the site of the new terminal. “With pipelines, at least there’s no active pollution.” Looking at the construction site, he added: “The industry in Omišalj is the reason why mass tourism has never been a thing here. If they bring the ship over, we’ll at least be protected from over-tourism.”

First published on 17 January 2020 on Balkaninsight.com.

This text is protected by copyright: © Balkan Insight / Jelena Prtorić. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures and graphics are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: The site of a new LNG terminal on the northern tip of the Croatian island of Krk. Photo: © BIRN

This article was produced as part of the Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.