Bulgaria faces huge demographic challenges, but optimists point to recent migration trends as cause for at least cautious optimism.

Google “Bulgaria” and “demography” and you will rapidly learn that journalists and analysts have for years been reporting that the country’s population is one of the fastest shrinking in the world. There is no way to spin it any other way. “I think it is clear,” said Sergey Tsvetarsky, the head of the National Statistical Institute, NSI, “that the situation is not so good.”

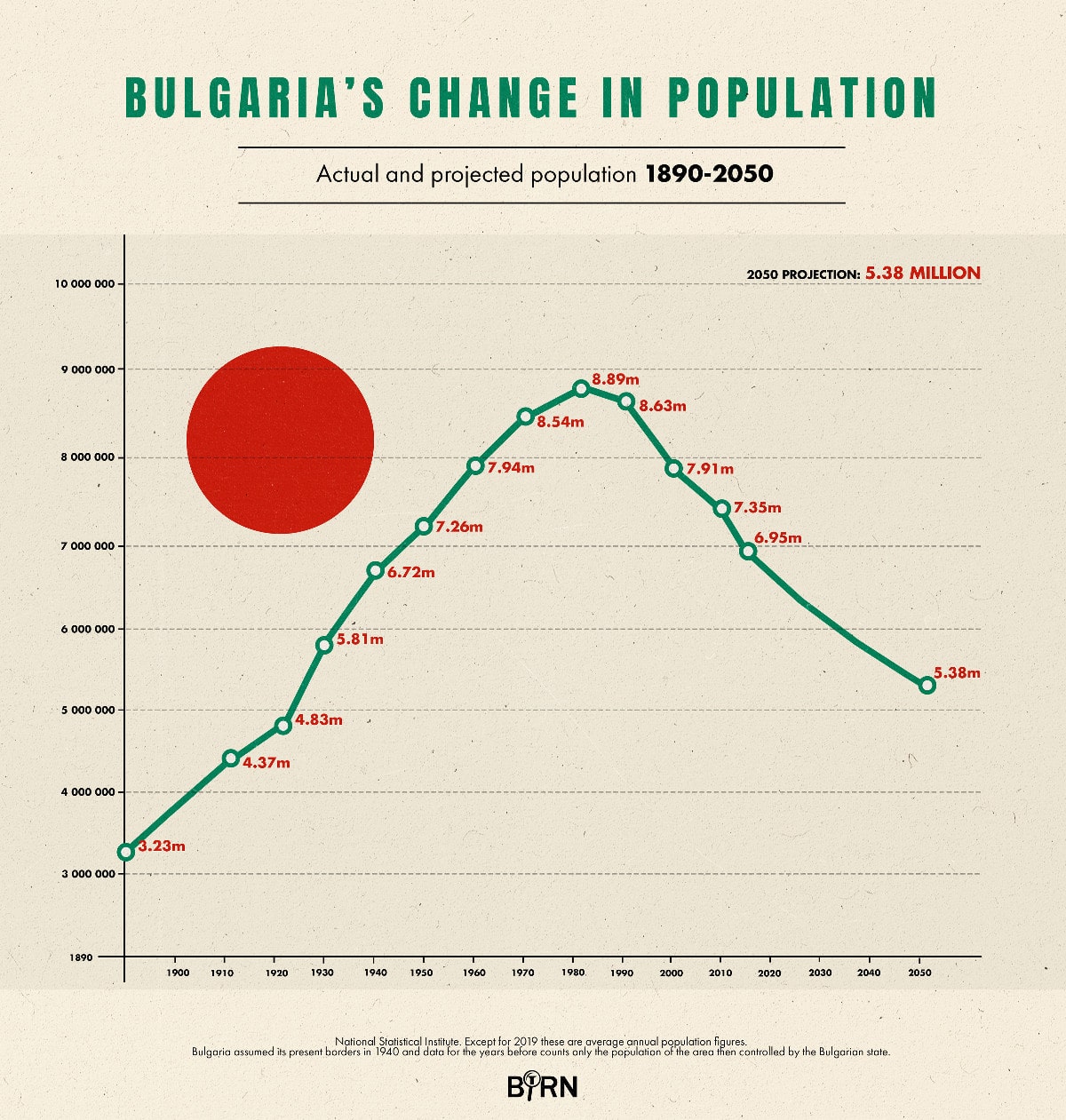

The headline numbers are stark. In 1988, Bulgaria’s population peaked at 8.9 million. Now it stands at 6.9 million. That means that, in little over three decades, the country’s population has fallen by an extraordinary 22.5 per cent. That’s an even more dramatic drop than that seen in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which endured four years of war. By NSI’s “realistic”, as opposed to pessimistic projection, the country’s population will continue to fall, resulting in a 35 per cent drop by 2050 compared to 1988.

In 1950, a record 182,571 babies were born in Bulgaria. With a few fluctuations, that number has drifted downwards ever since. Last year, there were 61,538 babies born in Bulgaria. 1950 also saw the country’s highest ever natural increase, meaning that in that year there were 108,437 more births than deaths. Ever since 1990 though, there have been more deaths than births in Bulgaria. Last year, 46,545 more Bulgarians died than were born.

For the last three decades, large numbers have emigrated, especially since Bulgaria joined the European Union in 2007. In 2010 there were 308,089 Bulgarian citizens registered as living in the EU28 plus the four countries of the European Free Trade Association, EFTA, though there could have been more living and working illegally and who later legalised their situation. Still, by 2019 that number had ballooned to 890,000.

In Germany alone there were 39,153 Bulgarians registered in 2005, a number which had risen by 820 per cent to 360,170 in 2019. Several hundred thousand also live in Turkey. According to Tsvetarsky, up to 1.5 million Bulgarian citizens now live abroad. He believes that Bulgaria’s rapid decline in population can be blamed half on emigration and half on natural causes.

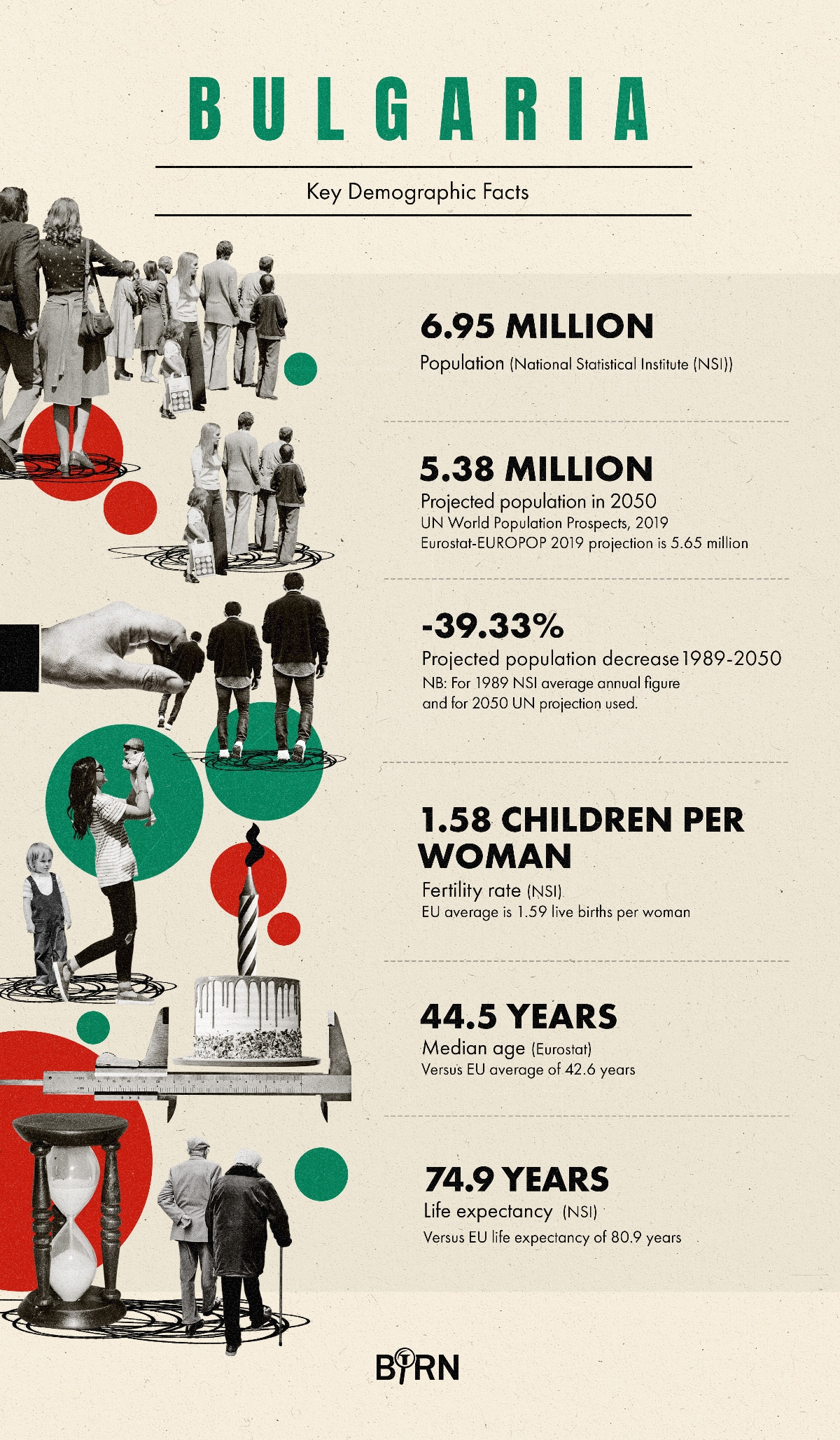

The latter is related to the country’s low birth rate. But with a fertility rate of 1.58, meaning that is the average number of children every woman has, it is almost exactly the EU average. However, during the difficult days in the wake of the collapse of communism, Bulgaria’s fertility plummeted to 1.1 in 1997. For a population to stay the same size, that number needs to be 2.1.

Apart from the fertility rate, what makes the situation so much worse than in most of the rest of Europe is a high mortality rate. From birth, a Bulgarian can expect to live to the age of 74.9, which is the lowest in the EU. By itself that figure conceals serious issues. Women, for example, live an average of seven years longer than men. According to Magdalena Kostova, director of demographic and social statistics at NSI, male life expectancy is lowered by an unusually high number of men dying in their 40s and 50s.

Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

After Romania, Bulgaria also has the worst rate of infant mortality in the EU, which in turn affects its life expectancy figure. Although there is no specific data on these two numbers, it is possible that they reflect deep problems affecting the health of Bulgaria’s mostly poor Roma minority.

Back and forth

To varying degrees all former communist countries in Europe suffer from the same underlying problems of ageing societies, low birth rates and emigration. But in every country the story has played out differently over the years.

In Bulgaria, a unique factor concerns the Turkish minority. Over the last century and a half, hundreds of thousands have emigrated, fled the country or been “exchanged” with Turkey. Likewise, before the Second World War hundreds of thousands of ethnic Bulgarians came to the country from Turkey and Greece.

EUROPE’S FUTURES

Europe is living through its most dramatic and challenging period since World War II. The European project is at stake and its liberal democracy is being challenged from both inside and outside. There is an urgent need from all quarters of state and non-state actors to address the burning problems, both to buttress what has been painstakingly achieved through the political peace project.

From 2018 to 2021, each year six to eight leading European experts are taking up engagement as Europe’s Futures fellows. They create a platform of voices presenting ideas for action whose goal is to reinforce and project forward a vision and reality of Europe. Europe’s Futures is an endeavour based on in-depth research, concrete policy proposals, and encounters with state and civil society actors, public opinion and media.

After the war, though, the emigration of Bulgarian Turks and Muslims continued. They left in waves, most famously in 1989. Then, following years of pressure by the Communist authorities to force the minority to “Bulgarianise”, including changing their names to Christian or Slavic ones, some 350,000 or well over a third of the community, fled when the country’s borders were opened for them.

While the precise figures are unknown, up to half of them then returned in the wake of the fall of Communism at the end of 1989, only for many to then depart once more as the economy collapsed during the 1990s.

In 2015, there were 378,658 people born in Bulgaria living in Turkey, a number which had shrunk by 100,000 in 15 years. Compared to Turks and Muslims who had immigrated to Turkey from the Balkans in the past, there were big differences with the Bulgarian Turks who had arrived relatively recently and who often kept close links with the country.

Unlike previous generations they could keep both citizenships and could travel back and forth to their old homes easily.

The fact that Bulgaria joined the EU in 2007, giving its citizens full rights to live and work there, also made its citizenship far more valuable than a Turkish one for anyone who wanted to go west.

Indeed, every summer large numbers return to renew their documents and, over the last few years, increasing numbers either retire back to their old homes in Bulgaria or return for work or to set up businesses. In 2019, some 14,640 people from Turkey came to live in Bulgaria, the vast majority of them Bulgarian Turks.

Until the 1990s Bulgarian Turks emigrated to Turkey but now, like other Bulgarians, they emigrate to the EU. There they join not just fellow Bulgarians from Bulgaria but thousands of ethnic Bulgarians from Ukraine and Moldova who have been granted Bulgarian citizenship plus many of the 81,000 citizens of North Macedonia who have opted to get Bulgarian citizenship.

Bulgaria Key demographic facts. Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

The idea of granting citizenship to Macedonians and ethnic Bulgarians abroad was dear to the heart of Bulgarian nationalists, said Marin Lessenski, an analyst at Sofia’s Open Society Institute. The policy was, “give them passports and they will come,” he said. However, “they took the passports and went to live in western Europe instead.” This means that a significant but unknown number of Bulgarians, registered by foreign countries as living there, are either Macedonians, or people who have never lived in Bulgaria.

From not enough jobs to too few workers

Over the last 30 years the story of emigration from Bulgaria has evolved in distinct chapters. First came the flight of the Bulgarian Turks, whose emigration needs to be taken into account when comparing Bulgaria’s population today with that of 1990.

This period was followed in the 2000s by increasing numbers who got to EU countries where many worked illegally. At first they went to work for the tourist season in Greece, for example, and in agriculture in Spain and Italy.

Bulgaria joined the EU in 2007 but many countries did not give its citizens full rights to live and work until 2014. From then on large numbers began to legalise their status and others emigrated. The last few years have seen a new chapter open. Bulgaria may be the poorest member of the EU, but every year, at least until the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, things have been improving economically.

The Return of the Gardeners

Who picked that fruit or harvested that vegetable you are eating? If you live in central or western Europe there is a sporting chance that it was dug up, picked or plucked by a Bulgarian. For more than two decades Bulgarians, either as immigrants or as seasonal workers, have been labouring in the fields and orchards of Spain, Italy, Britain and elsewhere.

Westerners might think that this is a relatively new phenomenon, but they would be wrong. For Bulgarians, the end of the Cold War not only meant they could travel again but also allowed the resumption of gurbetchiystvo, the centuries old tradition of practising a trade abroad.

Historian Marijana Jakimova wrote that Bulgarians began going abroad to work in horticulture more than 300 years ago. In the late 17th century the occupying Ottomans recruited Bulgarians to grow vegetables for their garrisons during their wars with the Austro-Hungarians and Russians. Later, they gained privileges in return for practising other trades. In the 1830s Bulgarian market gardeners are recorded as working in Belgrade.

As the 19th century wore on, Vienna, Budapest and other Austro-Hungarian cities began booming and growing so Bulgarians planted market gardens on their outskirts, to supply them. No different from today some settled where they worked while others returned home for the winter. Money was sent home to look after families and build homes.

The heyday of the Bulgarian market gardeners of central Europe was between the wars. In the wake of the Balkan and First World Wars Bulgaria was devastated but, at the same time, cities emerging from the chaotic collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire had to keep their people fed. In Austria the Bulgarians were granted privileges to keep their market gardens in business.

Between the wars the gardeners also worked in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Yugoslavia. So successful did they become in Austria though that local competitors tried to run them out of the country in the mid-1930s. That all changed in 1938 with Hitler’s seizure of the country. A predecessor of post-war gastarbeiter agreements was signed with Bulgaria. From then on, its agricultural workers became ever more important as, with the outbreak of the war, more and more were required to fill in for the Germans and Austrians being despatched to the fronts.

This chapter was to end tragically. Jakimova noted that those who returned home after the war were executed as “collaborators”. Agricultural workers were not the only ones to depart on gurbet though. Teams of builders, sometimes all the able-bodied men of a village, ranged across the Balkans and Asia Minor from spring to autumn during the 19th century.

Historian Dimitar Bechev also noted that, until the birth of the modern Bulgarian state in 1878, Istanbul, the Ottoman capital, was the largest Bulgarian urban settlement, attracting people for work and business. His own ancestors, from what is now the Bulgarian side of the Rhodope mountains in Thrace, worked as tailors on what is now the Turkish Aegean coast near Izmir – then Smyrna – where, as they spoke Greek, it was easy for them and their families to integrate with the now extinguished Greek communities there.

Bulgarians, like others across Europe, migrated in large numbers to the US from the latter part of the 19th century. There, Bulgarians typically gravitated to work in the industrial towns of Ohio, Pennsylvania and Indiana. In 1924, the Americans put a halt to mass immigration so those who followed often then left for South American countries like Argentina and Uruguay.

The end of Communism saw the door open to emigration and seasonal work once again. The 1990s provided more opportunities to the better educated, many who went to make Chicago and Toronto the biggest Bulgarian communities outside of Bulgaria. From the turn of the century though more began to emigrate and work, at first illegally in EU countries, and then gradually with EU accession in 2007, legally.

Now, however, the shrinking size of the population of working age has resulted in labour shortages replacing unemployment as a major problem. In 2001, Bulgaria’s unemployment rate stood at 20.3 per cent. In 2019, it was 4.2 per cent, and, according to economist Georgi Angelov, the country also had its highest ever employment rate.

In the 1990s, Angelov said, “the economy was so bad that people started leaving the country and moving west. And then the opposite happened. Because of the deteriorating demographic situation, we don’t have enough workers!” Things have “changed dramatically” in the last three years, he said.

Labour shortages have had several consequences. Wages have been going up by some 12 per cent a year, said Angelov. Foreign companies are discouraged from investing in Bulgaria but those already there are not withdrawing but rather opening up factories in previously neglected areas of the country. The rates of employment for older people and minorities are going up and, as wages shoot up too, Angelov said Bulgaria has been becoming “more and more attractive.” This means that net migration has been falling as more people either return to the country or immigrate.

Last year, for example, only 2,012 more people officially emigrated from the country than immigrated. That is a drastic change from a decade ago, said Tsvetarsky, when that figure was about 30,000. Broken down, however, the net migration figure reveals interesting facts. If we look at the numbers for Bulgarian citizens only, 14,376 more emigrated than returned but at 23,555, the number of returnees has never been so high.

In other Balkan countries a huge problem is that the authorities have no idea how many people leave the country and how many return. That used to be a serious issue in Bulgaria too, but much less so now.

More than ever before Bulgarians register if they go abroad to avoid double taxation and paying for health insurance twice. Increasingly they also re-register when they return to benefit from a plethora of services including everything from a place in a kindergarten for their children to getting a resident’s parking permit in parts of Sofia. For that reason Bulgarian data, which certainly still has holes, has never been as reliable as it is today. However, higher numbers registering today may not actually represent such high figures as opposed to more either regularising their situation at home or abroad, which they had not done before, or now simply registering movements which they had never bothered to do before.

Apart from Bulgarians returning, who else is coming to Bulgaria? Last year, 14,374 foreign citizens settled in the country while 2,010 left. Some immigrants were certainly Bulgarians, especially pensioners, who have acquired foreign citizenships, including Turks, but several thousand were Russians, including pensioners, who have been settling on the Black Sea coast in particular.

However, at least until the pandemic, better pay and conditions have also been attracting back increasing numbers of both young and educated Bulgarians. Hristo Boyadzhiev runs Tuk-Tam, which means “Here-There”, a networking organisation connecting diaspora Bulgarians with their homeland. He said there is a big change from the 1990s when those who left the country mostly did so “with no intention of coming back,” unless it was to retire. Today, he said, “opportunities are vastly different.”

Backdrop of discrimination

It is not just in the past couple of decades that Bulgarians, and especially nationalist politicians, have feared for the demographic fate of the nation. In the early 1980s, the Communists, worried by the falling birth rate and what that would mean, tinkered with ideas including luring young people to live in a quixotic and failed “Republic of Youth” in the Strandzha region of southeastern Bulgaria.

In the past, the higher birth rate of Bulgarian Turks led to fears that Orthodox Bulgarians would be outbred by them. Today, their birth rate is the same or lower and their proportion of the population is not believed to have changed from the 8.8 per cent it was in the 2011 census.

Bulgarian nationalists now focus on Roma with their higher birth rate, but no one knows their proportion of the population as many Roma don’t declare themselves as such. Few can name anything concrete that Bulgarian politicians have done to encourage Bulgarians to have more children, but one unspoken reason is likely to be that while they worry about this issue, nationalists who have controlled this portfolio in government in the last few years worry even more that financial incentives to encourage families to have more children would make no difference to Orthodox Bulgarians but would encourage the Roma they disdain to do so.

By contrast, labour shortages have meant that for the first time since the fall of Communism, Roma and Bulgarian Turks are finding jobs that discrimination barred them from before. If they don’t have the right skills, for the first time in decades employers, desperate for workers, are having to train them.

Low skills and low education standards in the country, related for example to poor pay for teachers, are long-neglected problems but are now being tackled by government. One element of this has been an attempt, over the last couple of years, to find children who have dropped out of school. What the authorities have discovered, though, is that many were no longer in the country, having emigrated with their parents. A large proportion of those who were however are Roma, many of whom are now back in education.

Cautious optimism

According to the NSI’s “realistic” projection, Bulgaria’s population will be 6.53 million in 2030, 5.8 million in 2050 and 4.9 million in 2080. Tsvetarsky errs on the side of optimism, especially if the net migration trend of the past few years continues and Bulgaria sees more people returning.

If economic conditions are good, then he believes the population will stabilise at about six million in the period 2040-50. But he cautions that it is wrong to be fixated on the number of Bulgarians as opposed to the structure of the population, meaning that Bulgarians are increasingly elderly and poorly educated. “These are things that deserve more attention,” he said.

The demographic challenges facing Bulgaria are huge. Today, the NSI is busily preparing next year’s census which, in terms of numbers, will be a moment of truth. Boyadzhiev of Tuk-Tam referred to Swede Hans Rosling who wrote a bestseller called Factfulness in which he argued that pessimism was often the result of judgements based on data which was no longer valid. “GDP is doing well, we’re growing, so I am more on the cautiously optimistic side.”

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN or ERSTE Foundation.

First published on 9 July 2020 on Reportingdemocracy.org, a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The article was produced within the framework of the Europe’s Futures project.

This text is protected by copyright: © Tim Judah. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures and graphics are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy