29 October 2018

Originally published

24 August 2018

Source

Sitting on the eighth floor of an old Socialist prefabricated apartment building in the Serbian capital Belgrade, Imre Kern, 69, talks about the future. Or rather, he talks about his last business trip to Beijing. “The high-speed trains are amazing,” says Kern enthusiastically, “it’s like flying.” He opens the photo gallery on his laptop. “Look at this platform!” he calls excitedly. “As clean as a mirror.” Kern clicks through images of Chinese carpets, dumplings and skyscrapers. For a moment he seems like a tourist who has just returned from his holidays.

Kern, a state secretary at Serbia’s infrastructure ministry, is an elderly official who studied chemical technology in 1970s Yugoslavia and received his training in the Soviet Union. Today Kern negotiates building contracts worth several billion euros on behalf of the Serbian government. They involve bridges, motorways, power plants, and the “largest project in Serbia’s history”, as Kern calls it: a high-speed rail line connecting Belgrade and Budapest. “It’s a good thing the Chinese provide us with translators during negotiations,” the state secretary says in passing, “because we couldn’t afford them.”

Big loans, small investments

Is China an important investor in the Western Balkans? No, the EU remains by far the largest donor in the region. In 2015, EU member states invested 21.8 billion euro in Serbia, China only 139 million euros. According to the Berlin Institute Merics, Chinese direct investment in the region does not even amount to the EU’s five per cent is not even 5 percent of those of the EU. China, however, is now in the lead when it comes to lending. Between 2007 and 2017, China granted Serbia USD 3 billion in loans. According to the Serbian Ministry of Infrastructure, the projects currently under negotiation with China have a value of 6 billion USD. The largest projects include: the construction of the Mihajlo-Pupin bridge over the Danube, the construction of the high-speed railway between Belgrade and Budapest, the expansion of the thermal power plant in Kostolac and a highway to the Montenegrin coastal city of Bar. China’s largest direct investment in Serbia 2016 was the purchase of the Smederevo steel plant for 46 million euros.

China plans to turn the Greek port of Piraeus – for which the Chinese shipowner Cosco Pacific has just received a 35-year concession for the modernization and operation of two container freight carriers – into a regional hub for trade with Europe. Photo: Ⓒ Medin Halilovic / Anadolu Agency / Getty

China has discovered the Balkans

A region that has been trying to catch up with the rest of Europe since the collapse of Yugoslavia. More than twenty years after the war, the countries still lack the means to renew their dilapidated infrastructure. This makes the Balkans the perfect gateway to Europe for China’s foreign-policy flagship project: a new Silk Road. With this infrastructure programme, President Xi Jinping aims to develop new trade routes between Asia, Africa and Europe. Chinese banks are extending loans to countries along the Silk Road. At a time when the EU is primarily concerned with itself, Beijing’s once-in-a-lifetime project comes at just the right moment for South-Eastern European countries. At the Greek port of Piraeus, China is helping to build Europe’s fastest growing container terminal. Chinese loans are paying for power plants in Bosnia and motorways in Montenegro. In Albania, Chinese firms have acquired a concession for the airport of Tirana and bought oil fields worth 450 million euros. There are plans to develop Macedonia into a bridgehead linking the port of Piraeus to the European rail network. And we shouldn’t forget the high-speed railway line, which brings us back to Imre Kern’s office.

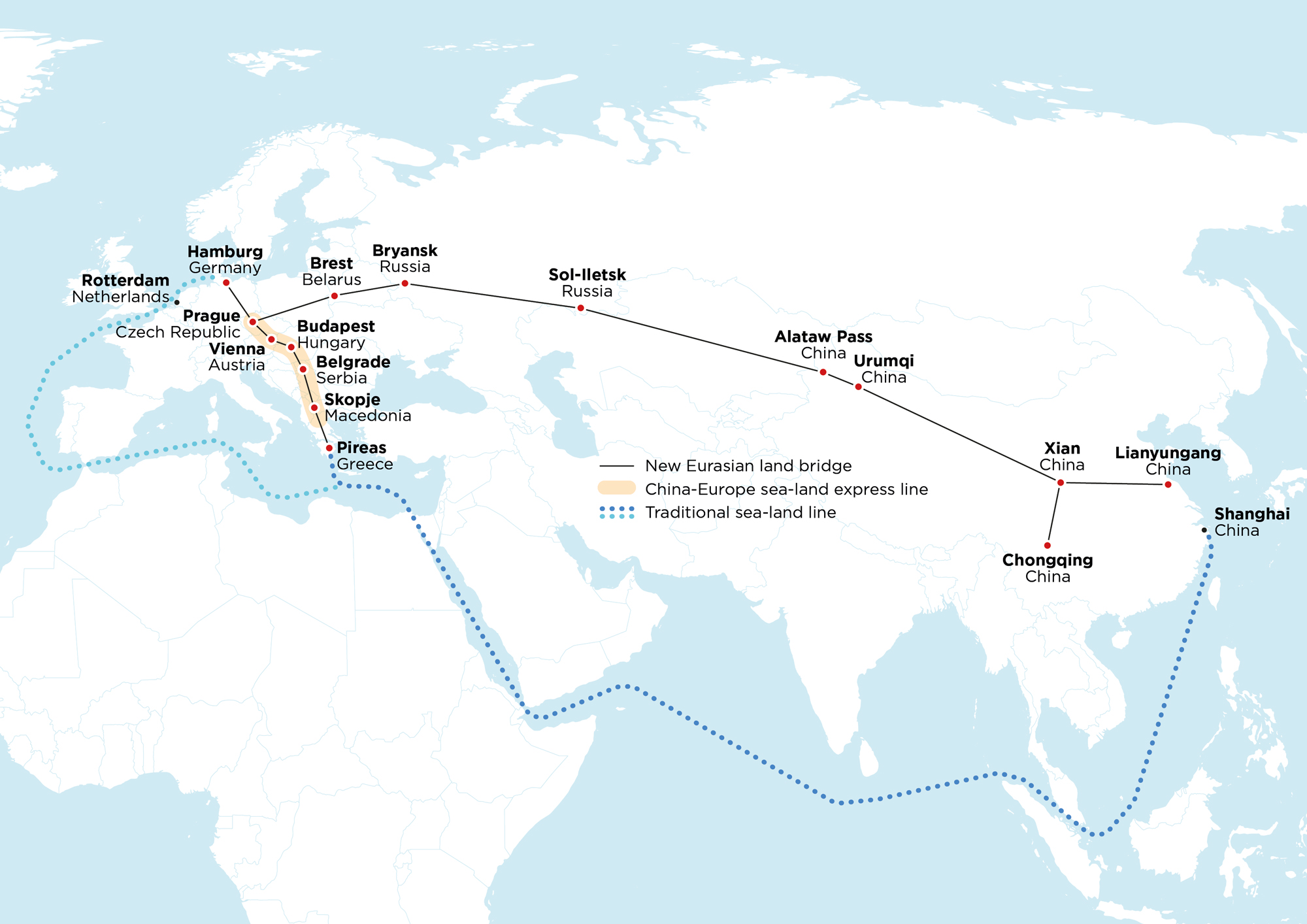

The project is expected to reduce travel time between the Serbian and Hungarian capitals from nine hours to two and a half. In the long run, the Balkan Silk Road could become the most important transport route for Asian goods travelling to Central Europe. A container vessel leaving the port of Athens and heading to Hamburg or Rotterdam must currently make a long detour through the Strait of Gibraltar and circumnavigate the whole of Spain and France. The land route is considerably faster. “And time is money for shipping companies,” says Nektarios Demenopoulos, spokesman of the Piraeus Port Authority, which has been majority-owned by the China Ocean Shipping Company (Cosco) since 2016. “We want to significantly increase the number of trains passing through the Balkans,” says Demenopoulos.

China’s economic involvement is viewed with suspicion in Brussels. The European Commission has launched infringement proceedings concerning the Hungarian section of the high-speed rail line, investigating whether the project had violated procurement laws.

The Chinese consider their approach a win-win strategy: in other words, a policy that benefits everyone involved. China promises cheap loans and fast negotiations. In return, the beneficiaries agree to contracts being awarded to Chinese construction companies. This raises a question nobody can currently answer: is an authoritarian one-party state gaining influence in a region whose countries are candidates for EU membership?

“China is holding a mirror up to us, by acting as sole provider of a clear strategy and incorporating the Balkans into the global Silk Road.”

“Yes, there is a risk,” says Jacopo Maria Pepe. He works for the German Council on Foreign Relations, a think tank that advises the German federal government for example. While China’s investment volume is still rather moderate compared to that of Western countries, Pepe thinks that Europe will be challenged as a regulatory power in the long term. “China is holding a mirror up to us,” says Pepe, “by acting as sole provider of a clear strategy and incorporating the Balkans into the global Silk Road.” Will Chinese investments create new political dependencies? The initial signs can be seen in highly-indebted Greece where Cosco acquired a majority interest in the port of Piraeus. For years the EU has unanimously approached the U.N. Human Rights Council to bring an action against China’s human rights record. In 2017, for the first time, Greece blocked the EU statement criticising Beijing. China’s foreign minister Wang Yi cheered, praising Greece for taking the right position. Is China becoming a divisive wedge? Serbian state secretary Imre Kern can only shake his head at that. “We’re clearly heading for Europe,” he says, running his fingers across a gold coin that sits on his desk like a trophy. It was a gift from the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC), a state-owned business that built an almost two-kilometre-long bridge across the Danube for the city of Belgrade in less than three years. It marked the kick-off of a huge wave of Chinese construction in Serbia. During inauguration, Serbia’s president Aleksandar Vučić described the bridge as “a monument of friendship between the two countries”.

The planned 350 km long high-speed rail link between Belgrade and Budapest will be part of the See-Land Express line from the Greek port of Piraeus to the heart of Europe. It is also a showcase project for Chinese President Xi Jinping’s “One Belt One Road” initiative. Source: ERSTE Foundation / Thomas Kloyber

No Western Balkan country has benefited more from Chinese funds than Serbia – one of the poorest countries in Europe. If you want to learn more about China’s strategy, go to Serbia. However, it seems that keeping quiet is also part of this strategy. Several enquiries made to the steel plant in Smederevo, which was bought up by a Chinese firm in 2016, went unanswered for weeks before they finally refused to comment – even though Smederevo is said to be a success story. China’s president Xi Jinping arrived in person to give a speech before Serbian workers. China’s state-owned HBIS Group had bought Smederevo for 46 million euros in the same year. The deal secured 5,000 jobs. Neither the Bank of China nor the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade wanted to comment on that. Transparency? “Far from it,” said an expert of the Serbian economic market willing to talk about his experience with Chinese investors – albeit anonymously. The meeting with the insider shows that it can be problematic in this sector to criticise China. Before this article was published, his spokeswoman called several times asking us to delete all details about the insider from the text: job title, office location, age. Was he afraid he might become a red rag for Chinese companies if he voiced criticism? His spokeswoman on the phone gave an embarrassed laugh.

The insider welcomed us in an air-conditioned conference room of his Belgrade office. First, he put a list of China’s largest building projects on the table. A tick indicated those that had already been completed. The rest were still up in the air, he said: an industrial park in Belgrade, for example, which the city government aims to develop into a kind of “Serbian Silicon Valley” with a 300 million euro loan. “The plot is reserved, there is a working group, but negotiations exclude the private sector,” said the insider. It was hard to get into that very particular “circle”, he said. When making deals, the Chinese offer what they term “packages”: “The Chinese bring money, they bring companies. Even the workers’ food is imported.” Later, sitting at the Italian restaurant around the corner, he pulled his smartphone out of his pocket, smirking. While waiting for his risotto, he wanted to show us a video he saw the week before in British comedian John Oliver’s American late-night show. In the video, Oliver makes fun of a campaign video released by China to promote the Silk Road. Cheerful children are playing the ukulele, holding hands and walking through a motley world of toys. “We tear down barriers. We write history,” the children sing. Two weeks after the late-night show went online, the BBC reported that state censors had deleted John Oliver from the Chinese internet.

President of Serbia Aleksandar Vucic meets with Chinese President Xi Jinping at The Great Hall Of The People in Beijing, China on September 18, 2018. Photo: © Lintao Zhang / POOL / AFP / picturedesk.com

According to Serbian prime minister Ana Brnabić, the value of the Serbian projects on the list totalled six billion dollars at the end of 2017. This is six times as much as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) invests in the entire Western Balkans in the course of a year. But there is a major difference. Serbia must pay back the Chinese money. “Often confused with direct investment, in reality these are what are known as soft loans,” says Vesko Garčević – former Ambassador of Montenegro in Brussels and Vienna. “Of all the geopolitical actors in the Balkans, China is the quietest but the most effective,” he claims. Beijing had managed to build “strategic partnerships” with the region’s governments within a few years, he explained during a Skype interview. Beijing has held its own economic summit called 16+1 since 2012. Participants include heads of state from 16 Eastern and South-Eastern European countries. The seventh summit took place in early July – in Sofia. “It is rumoured that Bulgaria was more interested in holding the Chinese 16+1 Summit than the EU summit in May,” said Garčević. Is China thereby creating exclusive negotiation formats? Zsuzsanna Hargitai, the EBRD’s new regional director for the Western Balkans, is diplomatic. She hopes that the summit will provide political impetus for enhanced cooperation between the countries. At the same time, she calls upon China to increasingly involve the private sector.

The alliance between Serbia and China is not new. In the 1990s China heavily criticised NATO bombing and supported the Milošević regime – which it regarded as the last bastion of communism in Europe. Milošević relaxed the visa regime and built up a Chinatown in Belgrade – known up to this day as “Blok 70”. Amidst apartment buildings, the decrepit market hall from the 1990s stands next to a new shopping mall. Inside, Chinese merchants sell neon coloured bikinis, fake brand-name trainers, flashing smartphone covers and more cheap junk. Outside, under a plastic sheet, a young Chinese is selling vegetables, glass noodles and soy sauce. He doesn’t understand English and uses his iPhone to translate the question of what he is doing here. After a few seconds, the answer pops up on his display. “China is very modern and is developing rapidly. We want to pass that on to Serbia. We should discover new things together!” Somehow the answer brings to mind the video about the Silk Road where children play the ukulele.

Original in German. First published on 24 August 2018 on nzz.ch.

Translation into English by Barbara Maya.

This text is protected by copyright: © NZZ / Franziska Tschinderle. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Is Montenegro’s highway a debt trap or road to success? Photo taken on 22 September 2018 shows the construction site of the Moracica bridge of Montenegro’s first highway, about 14 km north of the capital Podgorica. Photo: © Wang Huijuan Xinhua / Eyevine / picturedesk.com