North Macedonia’s official population statistics are not just a little off — they are dramatically incorrect. And that has consequences.

According to the State Statistical Office, the population of North Macedonia is almost 2.08 million — or to be precise, 2,077,132 as of 31 December 2018. The problem is this number is plain wrong.

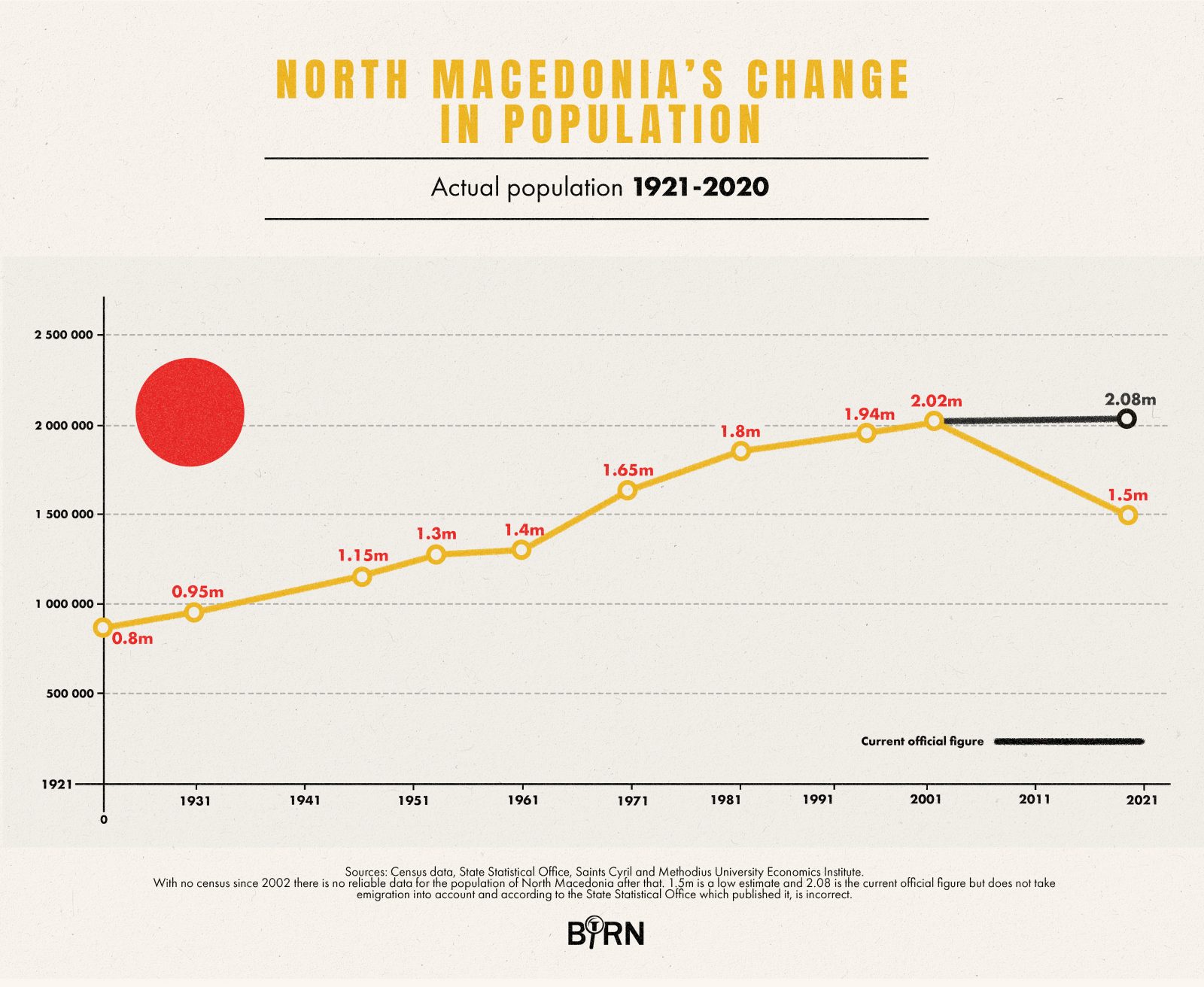

At least that is the view of Apostol Simovski, the State Statistical Office’s own director. “I’m afraid there are no more than 1.5 million in the country, but I can’t prove it.” If Simovski is right — and some think he is too pessimistic — then North Macedonia’s population would have fallen 24.6 per cent since independence in 1991 when the country had a resident population of 1.99 million.

This percentage would be far higher than for any other country in former Yugoslavia — even Bosnia and Herzegovina, which suffered four years of all-out war. It would also be even more dramatic than neighbouring Bulgaria, which has lost almost 21 per cent of its population in the past 30 years.

Some economists speculate that North Macedonia’s population is actually between 1.6 million and 1.8 million, which would still mean the country had lost between 19.6 per cent and 9.5 per cent of its population since 1991. If it is the latter figure, North Macedonia’s population loss falls within the same range as Serbia and Croatia, which have lost between eight and nine per cent of their populations.

North Macedonia’s change in population. Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

The problem is that no one knows the true number, and it is rare that the head of a national statistical office will admit that the most basic figure for their country is not just wrong but probably wildly so. “Believe me,” he said. “I’m frustrated.”

No consensus

There is a good reason why Simovski does not know for sure how many people live in North Macedonia. In 2011, Macedonian and Albanian politicians interfered to such an extent in the holding of that year’s census that the exercise collapsed. Macedonian nationalists wanted a result that showed that the country’s Albanian minority were less than 20 per cent of the population, he said. That is the threshold that gives ethnic Albanians certain rights under the Ohrid peace agreement of 2001, which pulled the country back from the brink of civil war.

In contrast to the Macedonian nationalists, ethnic Albanians unsurprisingly wanted to increase their share of the population by as much as possible. Both sides encouraged their supporters to add so many family members living abroad — and hence ineligible to be included — that before the census was over they realised the inflated numbers would be so incredible “that no one would accept them”, so they aborted the process, Simovski said.

A new census due to be held in April this year was postponed until 2021 because a snap general election was called for the same month. That election was then postponed because of the coronavirus pandemic. For that reason, North Macedonia still uses the population figure from the 2002 census as a baseline for all other data. Despite attempts at political interference back then, Simovski said the census was conducted well and can be considered reliable.

Thus, to get to today’s official population figure of almost 2.08 million, births and deaths and a very small number of immigrants and officially registered emigrants have been added to the 2002 census population figure of 2.02 million. The fundamental problem is that hundreds of thousands have emigrated — but are not registered as having done so, and no one knows how many they are.

However, Verica Janeska of Skope’s Saints Cyril and Methodius University’s Economics Institute cautioned against using foreign data for the numbers of Macedonians abroad to try to estimate the total number of people in the country. The reason, she said, is that these figures often contain “those who have left the country over the last four or five decades as well as second and third generation emigrants”. Also, while it might be possible to make rough estimates of the population based on various national databases, none of them — by themselves — are fully reliable. For example, tax data does not capture people in the grey economy. However, six national databases will, for the first time, be used to cross-reference the 2021 census. Until then, “no one can give a realistic estimation of the total population”, Janeska said.

North Macedonia. Key Demographic Facts. Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

So, until the 2021 census is completed, not only is North Macedonia’s official population figure wrong but so is the rest of its data, which is calculated on the basis of how many live in the country such as gross domestic product per capita. North Macedonia’s fertility rate is another example. Officially it stands at 1.42 children per woman, but if there are fewer than 2.08 million in the country, and hence fewer women of childbearing age, the fertility figure will be higher.

Follow the data

Macedonians have been emigrating since the late 19th Century but no one knows exactly how many live in the diaspora nor how many citizens are abroad. (See box.) According to a Yugoslav census of 1921, there were almost 809,000 people in what is now North Macedonia. By 1971, according to Janeska, who has subtracted figures for those abroad and who were included in the census total, the country’s population had doubled to 1.64 million. By 2002, of the 2.02 million in the country, 64 per cent were Macedonian, 25 per cent Albanian and the rest Roma, Turks, Macedonian Muslims and other minorities.

As everywhere else in Yugoslavia, the post-World War II period was one of industrialisation, urbanisation, education and social emancipation, especially for women. Across the world, these factors have always led to dramatic reductions in fertility rates and Yugoslav Macedonia was no exception. At the same time, more babies survived childbirth and improving healthcare led to people living longer lives. All of this can be followed in the data.

EUROPE’S FUTURES

Europe is living through its most dramatic and challenging period since World War II. The European project is at stake and its liberal democracy is being challenged from both inside and outside. There is an urgent need from all quarters of state and non-state actors to address the burning problems, both to buttress what has been painstakingly achieved through the political peace project.

From 2018 to 2021, each year six to eight leading European experts are taking up engagement as Europe’s Futures fellows. They create a platform of voices presenting ideas for action whose goal is to reinforce and project forward a vision and reality of Europe. Europe’s Futures is an endeavour based on in-depth research, concrete policy proposals, and encounters with state and civil society actors, public opinion and media.

In 1952, the number of live births peaked at just over 51,000 and in 1954 the republic’s natural increase — that is to say, births minus deaths — peaked at almost 34,300. Ever since, both these numbers have declined.

Last year, according to preliminary data, there were 687 more deaths than births, which would make 2019 the first time in history that deaths have exceeded births in the country.

Although there is no separate data for fertility rates for Macedonians, Albanians and other ethnic groups, Simovski and other experts believe that while in the Yugoslav period their demography was radically different, in recent years they have converged. But he noted that ethnicity is not the key factor in North Macedonia as opposed to religious and hence cultural background.

Thus, Macedonian Christians began having far fewer children much earlier than Muslims, a cultural phenomenon that was paralleled in other parts of former Yugoslavia including Kosovo and Bosnia.

Of course, the largest part of the Muslim population of North Macedonia is ethnic Albanian. Izet Zeqiri of South East European University in Tetovo said Albanian demographic trends in North Macedonia parallel those of Kosovo Albanians, which is to say a previously high birth rate that has collapsed over the past 30 years.

So while North Macedonia’s official if inaccurate fertility rate is 1.42, for the overwhelmingly Albanian-inhabited Polog region, it was 1.17 in 2018, which is even less than in some solidly Macedonian regions. This reflects not just a sharp decline in the birth rate but the emigration of women of childbearing age too.

Because so many have left, North Macedonia has begun collating the data of babies born abroad who are registered as citizens. It is a crude statistic because other countries do not share information about babies who have their citizenship too, and not everyone abroad registers their babies with the Macedonian authorities. Still, the number grows annually. In 2008, there were around 3,700 babies born abroad and in 2018 there were some 5,000. This means that almost one Macedonian baby was born abroad for every four at home. Like everywhere else in Europe, Macedonians are getting older. Today life expectancy is 75.95 whereas in 1960 it was 60.6.

At the other end of the age scale, declining numbers mean fewer pupils in school every year. In 2018, there were 188,500 school students but in 2009, after upper secondary education had been made compulsory, there were 209,000. That is a decline of almost 10 per cent in less than a decade. At the same time, almost all regions of the country have lost population apart from Skopje. But now, according to Nikola Naumoski, the chief of staff of the mayor of Skopje, even the capital’s population is stagnating at around 600,000. While people from the rest of the country are still moving to the city, many of its residents are leaving the country at the same time, he said.

Labour shortages

Declining numbers are beginning to hit the economy. For decades, North Macedonia has been plagued by unemployment but now the number of those without jobs is declining because there are fewer young people coming onto the labour market and because of emigration. In the past three years, labour shortages have begun to bite seriously in certain sectors, said Silvana Mojsovska of the Economics Institute.

Services, particularly tourism, have been hard hit. Other sectors that lack labour are IT and retail. Doctors, medical professionals and construction workers are also leaving, or were until the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. In the last few years, North Macedonia’s GDP has never increased by more than 3.8 per cent in any given year — and that is just not enough, Janeska said. It would need to be consistently double that to result in an economy growing fast enough to be able to make staying at home more attractive than leaving.

In the wake of the global pandemic, it is unlikely that the economic situation in North Macedonia will improve and the effect on the rest of Europe and the world will also affect emigration, but so far it is too early to predict how things will change. As elsewhere in the region then, people were leaving until the outbreak of the pandemic and may continue to do so afterwards, and not just because of money, said Janeska, but also for better career opportunities, for education, healthcare and to live in less corrupt and more politically stable environments.

Counting Macedonians

One reason no one knows how many people live in North Macedonia is that no one knows how many people have left the country, especially since the last census in 2002. The problem with trying to come up with a figure for Macedonians abroad is that it depends on how you define who should count as a Macedonian. And even if you define it just as those who have Macedonian citizenship, you rapidly discover that the data available is patchy and unreliable.

Unverified numbers are bandied about in political debate as if they were somehow accurate and verified. There is little understanding that numbers quoted by otherwise reputable organisations like the World Bank or the United Nations give ballpark figures but are otherwise extremely rough and ready. The reason for this is that such organisations do not collect their own data but have to rely on figures from others. The first thing to understand is whom exactly we are talking about or counting when it comes to numbers. Are we talking about ethnic Macedonians, citizens of Macedonia or the descendants of people who left Macedonia in the past?

If it is the latter, then it is important to remember that many of their ancestors emigrated from a region that is far bigger than today’s North Macedonia. Macedonians have been emigrating in large numbers since the late 19th Century, which means that, by any definition, there are going to be a large number of people abroad of Macedonian descent or people whose roots are in Macedonia. The United Macedonian Diaspora (UMD), which is based in Washington, D.C., represents ethnic Macedonians. Thus Albanians, Turks, Roma and other minorities from what is now North Macedonia are not included in their guesstimates of the numbers of Macedonians abroad. The UMD claim there are up to 250,000 people of Macedonian heritage in Canada, up to 300,000 in Australia, up to 600,000 across Europe excluding North Macedonia itself and 500,000 in the United States. That comes to a total of 1.65 million.

However, a significant but unknown proportion of those people descend from emigrants who left Ottoman Macedonia, which included Thessaloniki, now Greece’s second city. The Balkan wars of 1912-13 saw this territory divided into three. While a small part was incorporated into Bulgaria, the bulk was divided between Greece and Serbia. At the end of World War II, the latter became one of Yugoslavia’s six republics, which in turn became today’s North Macedonia. The end of World War II in Greece also gave way to a civil war that saw the flight of tens of thousands of ethnic Macedonians, often called Aegean Macedonians. As with Greek Macedonian refugees, many were evacuated to the Soviet Union (Tashkent in Uzbekistan in particular) and other Eastern Bloc countries. Others fled to Australia, the United States and Canada.

Thousands, however, came to Yugoslav Macedonia directly but many who did not trickled in from the Soviet Union and elsewhere in the two decades after the war. By the mid-1960s, some 50,000 Aegean Macedonians are estimated to have made their home here. However, some were also settled in Vojvodina in northern Serbia. Until the mid-1960s, emigration from Yugoslavia was either illegal or at least extremely hard. For Macedonia, there was a major exception though. An agreement between Turkey and Yugoslavia allowed Turks from Macedonia to emigrate freely. According to the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 170,000 Turks did so between 1953 and 1968. However, while the majority were ethnic Turks, many others such as Albanians and Macedonian Muslims declared themselves to be Turks in order to leave. The difference between these people and the ethnic Macedonians who emigrated is that while in the diaspora the latter often fiercely guard their Macedonian identity, those who went to Turkey soon identified completely as Turks.

When Macedonians abroad show up in foreign data, it means they are citizens and so ethnicity is not a factor. However, it is clear that in some countries different nationalities tend to group together. Albanians are the vast majority of Macedonians in Switzerland, for example. Macedonian Muslims go to Italy and ethnic Macedonians tend to go to Slovenia and Sweden. If those abroad have also acquired the citizenship of another country, then mostly they no longer show up in the figures. Australia, by contrast, gives a figure of just over 49,000 for those resident who were born in what is today North Macedonia.

In Europe, according to Eurostat data, which in turn comes from national statistical agencies, on 1 January 2019 there were 102,000 Macedonians in Germany, 66,600 in Switzerland, 63,600 in Italy, 23,400 in Austria and 12,300 in Slovenia. According to Eurostat, there were 156,900 Macedonian citizens in the EU in 2010 and 220,400 in 2019. But, as with all such figures, they are also problematic. Firstly, at least 81,000 Macedonians have acquired Bulgarian passports, which means they can work easily in the EU. Thus, any Macedonian registered as a Bulgarian in the EU will not show up in the data as a Macedonian. Secondly, according to Apostol Simovski, the director of the State Statistical Office, foreign data showing Macedonian citizens abroad does not show where they came from.

For example, the number of Macedonians in Italy is dropping, while their number in Germany is increasing. It would be wrong, therefore, to assume that those arriving in Germany or elsewhere are new emigrants from North Macedonia and hence that its population has dropped by the same number as the new arrivals may have left the country years ago. Thirdly, Eurostat figures — and hence the national data from which they are compiled — are puzzlingly patchy. Eurostat records the number of Macedonians in Greece, Spain, Britain, Malta and Croatia as zero.

In fact, for example, there are estimated to be 3,000 Macedonians living in Britain, not including those registered as Bulgarians, according to the Office for National Statistics. At the end of 2018, there were 1,591 Macedonian citizens with residence permits for Malta. If you Google “How big is the Irish diaspora”, the top search result yields an article from The Irish Times that says “three to 70 million, depending on who is talking”. There are 4.83 million people in the Irish Republic. In terms of Macedonians abroad, they seem to be taking on the mantle of the Irish of the Balkans, except that unlike the Irish, they do not even know how many people live at home.

Mojsovska added that worsening pollution was another factor pushing even well-paid professionals to leave. They are taking their children’s health into account, even if their standards of living are worse outside the country. Going abroad for seasonal work is a deep-seated tradition in North Macedonia. While there is no hard data, it is clear that the phenomenon continues to this day.

Officially, for example, there are almost 1,600 Macedonians with residence permits for Malta. But Edmond Ademi, the Minister of the Diaspora, said that when he visited Malta he was told that in summer that number swells to up to 7,000. However, since many use Bulgarian passports, it is impossible to prove. “How can you create an economic policy without knowing who is here and who is not?” Janeska said.

“How can you create an economic policy without knowing who is here and who is not?”

People are being “pulled” towards Germany and other countries that are opening their doors to labour from North Macedonia, an EU candidate country, and simultaneously “pushed” by low salaries and poor conditions at home. One effect, she said, is that foreign investors are complaining. “They say, ‘You promised us you had a labour force but now there is a lack of labour.’” And this, she added, “is a big economic problem”.

Unlike in richer Balkan countries such as Croatia, no one wants to come from abroad to work for Macedonian wages and conditions. The demographic situation in North Macedonia is clearly dramatic but until there is a census no one will know how bad it is. And it will remain hard to plan properly for the country with no proper statistics. In the meantime, demographers say it is important to remember that the issue concerns real people — not just numbers.

Janeska often visits family and friends in and around the northwestern city of Gostivar. She said that in winter “the city is more or less empty”. It fills up only when the diaspora are home in summer. Most people who live there all year round are old. “They are very upset,” she said. “They say: ‘We are alone. Our children and grandchildren are abroad. They send us money, but we don’t want money. We want our families back.’”

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN or ERSTE Foundation.

First published on 14 May 2020 on Reportingdemocracy.org, a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The article was produced within the framework of the Europe’s Futures project.

This text is protected by copyright: © Tim Judah. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures and graphics are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy