Romania’s failure to prevent a deadly measles outbreak is a story of complacency, bungling and discrimination. It is also a cautionary tale for Europe.

Karla was never vaccinated against measles. Her health would not allow it. Born with an interrupted oesophagus, she spent her infancy in and out of hospital, often with pneumonia. During a routine stay at the Louis Turcanu Emergency Children’s Hospital in the western Romanian city of Timisoara, the toddler was on the same floor as a girl who had measles. Soon, Karla developed a fever. She was transferred across town to the Victor Babes Clinical Hospital for Infectious Diseases and Pneumology. The place was so full of measles patients that at first Karla had to stay in an adult ward. Her fever worsened, rising as high as 42 degrees Celsius.

During the night of December 18, 2016, she started moaning in a way her mother, Florentina Marcusan, had never heard before. She had a rash on her face and chest. Shortly after 8 am, as a nurse was giving Karla an injection, the girl’s head started twitching. While the nurse ran to get help, Marcusan held her child. “When I saw that she wasn’t reacting anymore, I panicked and put her down, because I knew she had died… in my arms,” she recalled. Doctors sent the distraught mother out of the ward while they tried to resuscitate the girl. She waited in the cold in front of the building, smoking cigarette after cigarette and holding Karla’s teddy bear. Forty-five minutes later, at 9.10 am, Karla Iasmina Georgiana Popa was declared dead. She was one year and three months old.

The little girl was one of the first 10 victims of a measles outbreak in Romania that as of late November had killed 36 people – mostly babies – and infected around 10,000 since the first cases appeared last January. It is the country’s deadliest epidemic since 2005, when Romania’s two-shot vaccination regime against measles, mumps and rubella, MMR, came into effect. Measles cases linked to Romania have been detected as far afield as Belgium, Spain and Ireland, though those outbreaks are tiny compared with the epidemic that killed Karla. The girl’s mother blames the hospitals she stayed in for not doing more to protect her. “I have such hate in me,” Marcusan said, speaking six months after Karla’s death in her native village of Dubesti, about 90 kilometres from Timisoara. “I don’t trust anyone anymore.”

A lack of trust is at the heart of the measles crisis in Romania, where faith in health services is tainted by perceptions of poor conditions and mismanagement. Despite the availability of free MMR jabs at family doctors, given to children in two doses several years apart, vaccination rates have fallen sharply. According to data from the World Health Organization, WHO, and the Romanian health ministry, rates for the first shot have fallen 11 per cent over the past decade, and 29 per cent for the second.

Florentina Marcusan studies medical records of her deceased daughter, Karla. Photo: © Octavian Coman

Many are quick to blame the epidemic on a strident anti-vaccine movement, but doctors and public health experts also point the finger at the Romanian authorities, describing a systemic failure to ward off a foreseeable crisis. From mismanaging vaccines stocks to sounding the alarm too late, they paint a picture of bureaucratic bungling and complacency — with deadly consequences. “The immunisation programme can’t be better than the health system that hosts it,” said Eduard Petrescu, a coordinator at the United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF, in Romania.

Others see a cautionary tale for what happens when authorities fail to bring marginalised communities – in this case, the Roma minority – into the fold of national healthcare. “If you don’t vaccinate continuously, systematically and assiduously, the virus immediately fills the gap,” said Adriana Pistol, director of the Centre for Surveillance and Control of Communicable Diseases in Romania, part of the National Institute of Public Health under the health ministry.

The science of measles

Measles is one of the most contagious human diseases. Before the discovery of a vaccine in 1963, it claimed more than 2 million lives and infected some 30 million people each year. Here are some key facts about the disease.

* Measles kills one or two people for every 1,000 who contract the virus.

* There is no specific treatment other than relieving symptoms.

* First symptoms often include fever, coughing, conjunctivitis and general malaise. Two to four days later, a characteristic rash usually appears.

* Patients tend to be contagious from around four days before the appearance of the rash until four days after its eruption.

* Measles is most deadly in children under five. Children who are malnourished, deficient in vitamin A or who have immunological disorders such as HIV/AIDS are most vulnerable.

* Common complications include pneumonia, diarrhoea, otitis and croup.

* In rare cases, measles can cause swelling of the brain, which can leave children deaf or mentally disabled.

* The World Health Organization recommends that children be vaccinated twice. The timing of doses varies by country but the first is usually done at 12 months.

* If a population is widely vaccinated, measles has a much harder time spreading, meaning that even people who have not been vaccinated gain protection because the virus is not circulating in the community. This is known as herd immunity.

Sources: WHO, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, Centre for Surveillance and Control of Communicable Diseases in Romania.

Photo: © Tudor Vintiloiu

Outside the system

Before the invention of a measles vaccine in the 1960s, nearly all children caught the disease by the time they were 15. The highly contagious virus is transmitted through coughing, sneezing or contact with infected secretions. Prior to mass inoculation campaigns, major epidemics broke out every two or three years, killing on average 2.6 million people worldwide, according to the WHO. By 2016, the global death toll had fallen to around 90,000 a year.

The measles vaccination was first introduced in Romania in 1979, but it was not until 2004 that a combined MMR jab became part of the free national immunisation programme. A year later, a second jab of MMR was added. Normally, children are inoculated at the ages of one and five. MMR vaccination rates stood at 97 per cent for the first jab and 96 per cent for the second in 2007, more than the 95 per cent minimum recommended by the WHO to keep a lid on measles. But they had fallen to around 86 per cent for the first shot and 67 per cent for the second by 2016, when the latest outbreak hit, data from the health ministry shows.

The figure was likely even lower for members of the Roma community, the country’s second-largest ethnic minority after Hungarians. According to a 2012 study by UNICEF and other organisations, 45 per cent of Roma children had not received all the vaccines in the national immunisation programme. Community health workers say Roma families may be cut off by circumstance or choice. Some are not registered with doctors because they lack identification papers. Others have itinerant lifestyles. Discrimination is also a factor.

According to a 2013 study by the WHO, “the perceived low quality of the interaction with medical practitioners represents a major deterrent [for Roma] from seeking medical help”. The study revealed a range of discriminatory practices by health services including use of derogatory language, limited physical contact during medical examinations and segregation in maternity wards. It was in a Roma community that the latest measles outbreak first got a toehold, around the village of Reteag in northern Romania, according to health officials.

The Roma of Reteag are relatively prosperous. Houses here are big and new. Some have gates adorned with lion statues. Many children have Italian-sounding names: Ricardo, Francesca, Mateo or Zoro. Mayor Vasile Cocos explained that residents spend a lot of the year in Italy, a pattern of migration that dates back to the fall of communism in 1989. Roma traders from the village typically travel to Naples to buy up clothes and household goods, which they sell in other parts of Italy. After one such visit, two Roma children, aged 7 and 9, brought measles back to Romania, in January 2016.

Health officials know the virus originated in Italy because of its tell-tale B3 strain. If it had started in Romania, it would have had the D4 genetic fingerprint of past outbreaks.

In Reteag, many parents had taken their children to Italy before they were old enough for shots, said Mihaela Catana, a nurse who acts as a liaison between the local family doctor and the Roma community. “We still have this migration […] I’m afraid of other diseases, like polio, with more dangerous consequences,” she said. Ana Lingurar, 56, helped nurse two of her eight grandkids back to health after they returned from Italy with measles. The boys had not been vaccinated, probably because they were abroad when they should have received jabs, she said. “In Italy, if you’re not on the list of a family doctor, they’re not interested in your child,” she said.

“It isn’t a priority”

By August 2016, measles cases were reported across more than half the country, infecting people from all ethnicities, rich and poor alike. None of this came as a surprise to Adriana Pistol from the Centre for Surveillance and Control of Communicable Diseases. In 2015, she had noticed alarmingly patchy vaccination coverage. For example, only half of the children in the western district of Timis, home to some 700,000 people, had received the first MMR jab, data from the local health authority shows.

She took her concerns to the health ministry, warning of a looming epidemic. “Let’s say this is coming: if you have children, go and vaccinate them,” she recalled that she told them. “Say something, goddammit! […] It isn’t a priority. In many fields, we work as firemen. We do something only when a fire starts.” By January 2017, as the death toll in Romania topped 10, the government was urging parents to vaccinate their kids. The health ministry had also decided a month earlier to introduce a supplemental MMR jab for babies aged nine months as a temporary crisis measure. But many turned up at family doctors only to be turned away.

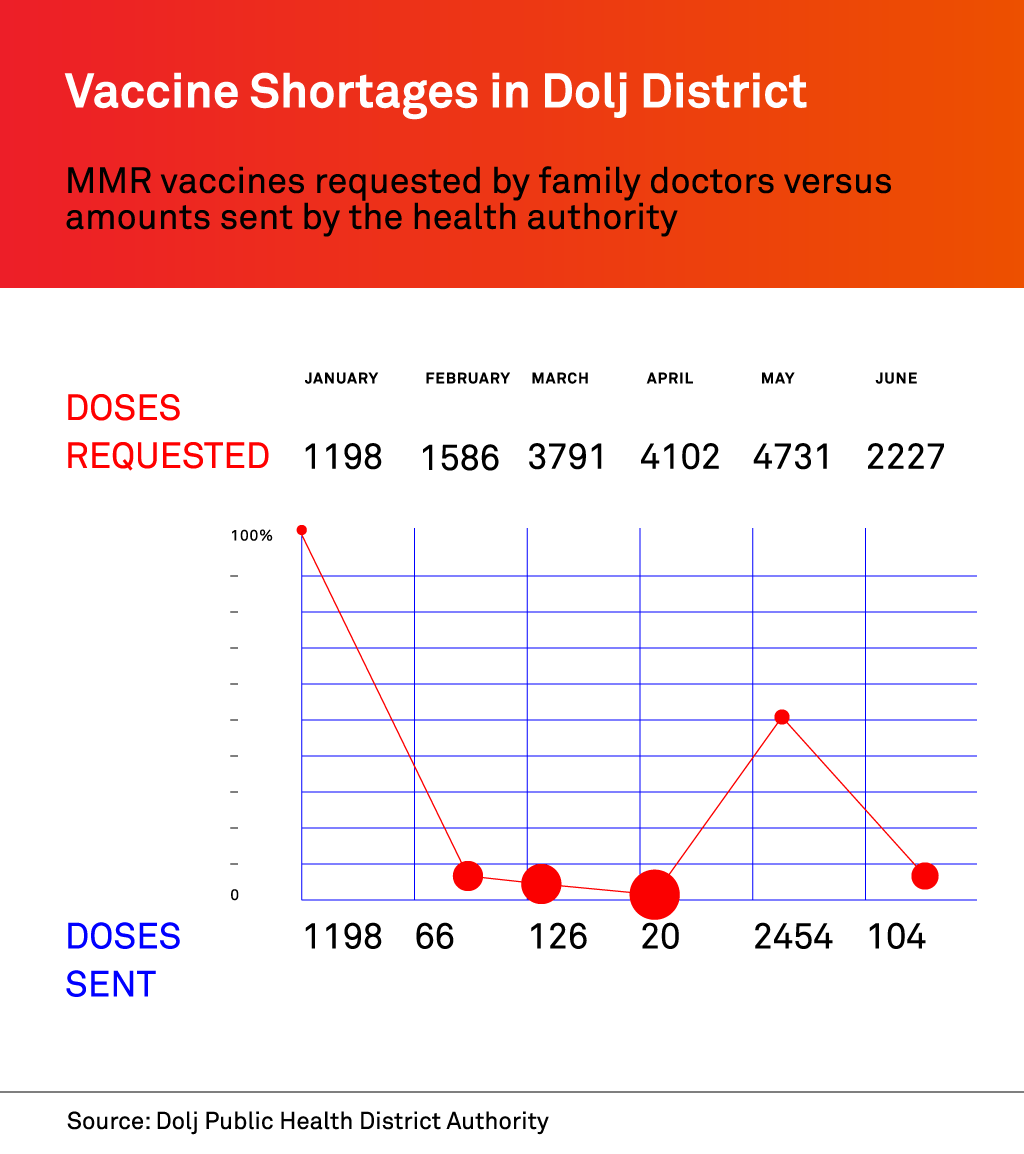

Health ministry data showed that in April 2017, around 36,000 MMR jabs were available nationwide, four times fewer than in the same month a year earlier. Frustrated doctors said the government was late in ordering extra stocks. Dalida Mosorescu, a family doctor in the southern city of Craiova, said in July that she had been waiting for a delivery of MMR shots for two months – even as the health ministry was assuring people that stocks were available.

“Some patients understood that I didn’t have them,” she said. “It wasn’t like I was drinking the vaccines or injecting them into myself. Some were angry: ‘Hey, lady, I’ve seen on TV [that vaccines are available]. Why don’t you give the shot?” Her experience was not unusual. Data obtained from the local health authority showed that in Dolj district, of which Craiova is the capital, doctors got only 20 of the 4,102 shots they requested in April. Other months had extreme shortages too.

A spokesman for the Dolj Public Health District Authority said he had no precise information on the cause of the shortages. Meanwhile, a health ministry report shows that as of the end of July, more than 224,000 children aged nine months to nine years were not vaccinated against measles nationwide. The report underlines that authorities had insufficient stocks and budget to deal with an outbreak. “If you show up at the local clinic and you want to vaccinate your child and there is no vaccine, you are less likely to come back next week,” said Robb Butler, European programme manager for vaccine-preventable diseases at the WHO.

Political instability did not help. Since late 2015, Romania had been ruled by a government of technocrats following the resignation of the then prime minister amid public fury over a deadly nightclub fire. After parliamentary elections ushered in a Social Democrat-led government in January, new Health Minister Florian Bodog criticised his technocrat predecessor, Vlad Voiculescu, for leaving behind what he described as a “disaster” regarding vaccine stocks. Voiculescu defended his legacy, saying MMR stocks were adequate when he left the ministry.

Bodog declined an interview request but the health ministry responded to a list of questions. The ministry said there had been no MMR vaccine shortages between 2015 and 2017 but that the new supplemental jab for nine-month-old babies and catch-up campaigns had put pressure on supplies. The former technocrat minister, Voiculescu, told us that once vaccine stocks fell below a certain level, the ministry should have scrambled to get more. “It’s a problem of management,” he said.

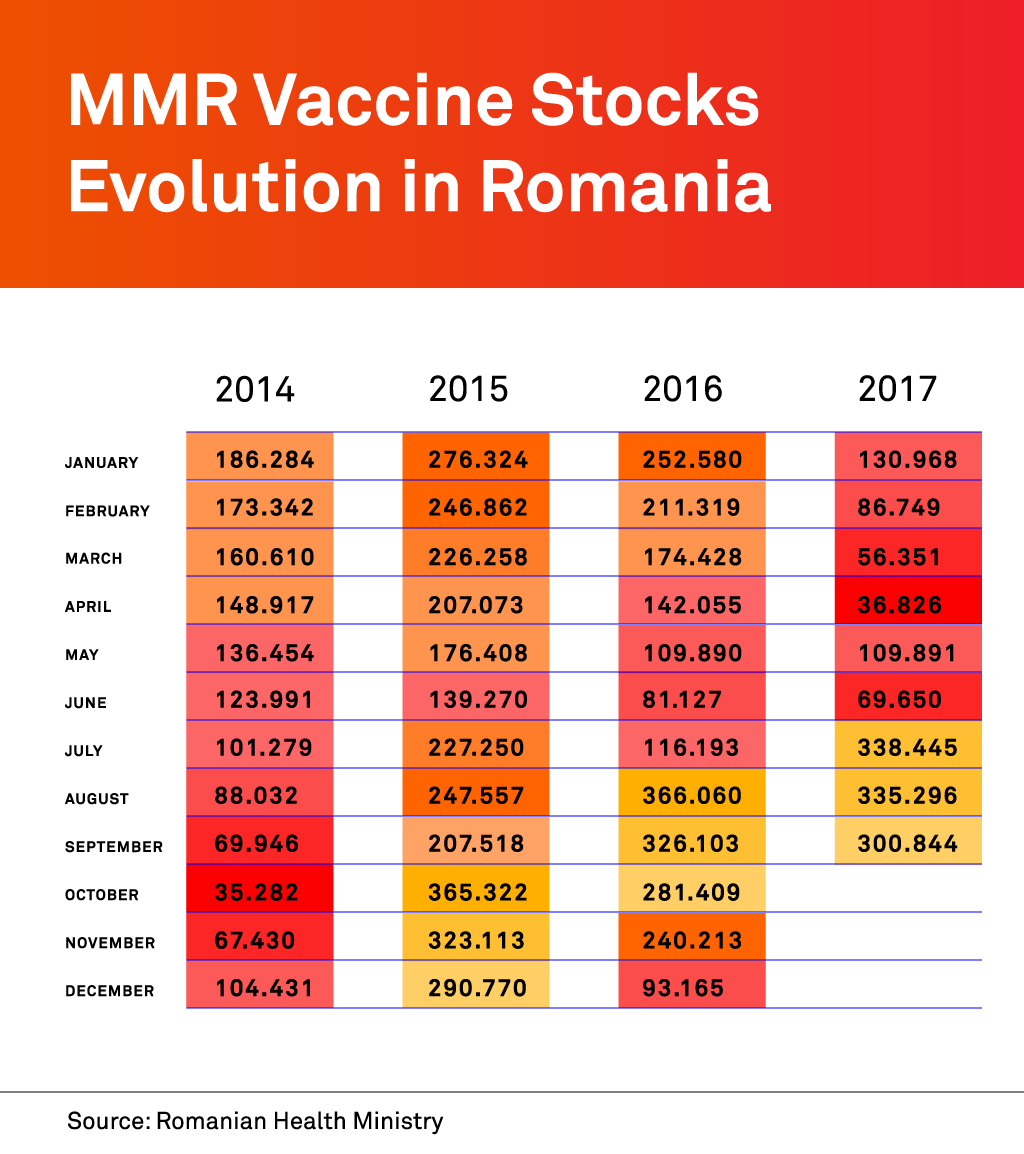

MMR stocks finally recovered, but only after the government signed a big new contract with a supplier in early July. According to health ministry statistics, 338,445 doses were available nationwide in July, compared with 116,193 in the same month a year earlier and 227,250 in July 2015.

Ditta Depner, a Romanian anti-vaccine personality, doubts the science of vaccinology. Photo: © Tudor Vintiloiu

Upset anti-vaxxers

The government is pushing for a law to make vaccines compulsory. If approved, draft legislation before parliament could take effect in 2018. The move has vaccine sceptics up in arms. In August, about 200 so-called anti-vaxxers protested in Bucharest. One banner read: “Mandatory vaccination is mandatory death!” More protests followed in the autumn during parliamentary debates on the new law.

Some anti-vaxxers worry that MMR jabs may cause autism, a fear stemming from long discredited research by a disgraced British former doctor. For Ditta Depner, a well-known vaccine skeptic in the central city of Brasov, the very science of vaccinology is at fault. The mother of a boy and a girl – both unvaccinated – teaches courses on natural birth and believes diseases have emotional causes.

“This craziness with measles and ‘outbreaks’ are just inventions of the pen.”

“Fever means great interior anger,” she said, sporting a large silver medallion as she sat in a park. Depner is convinced measles cases reported in Brasov were fabricated to scare people into vaccinating their children. “This craziness with measles and ‘outbreaks’ are just inventions of the pen,” she said.

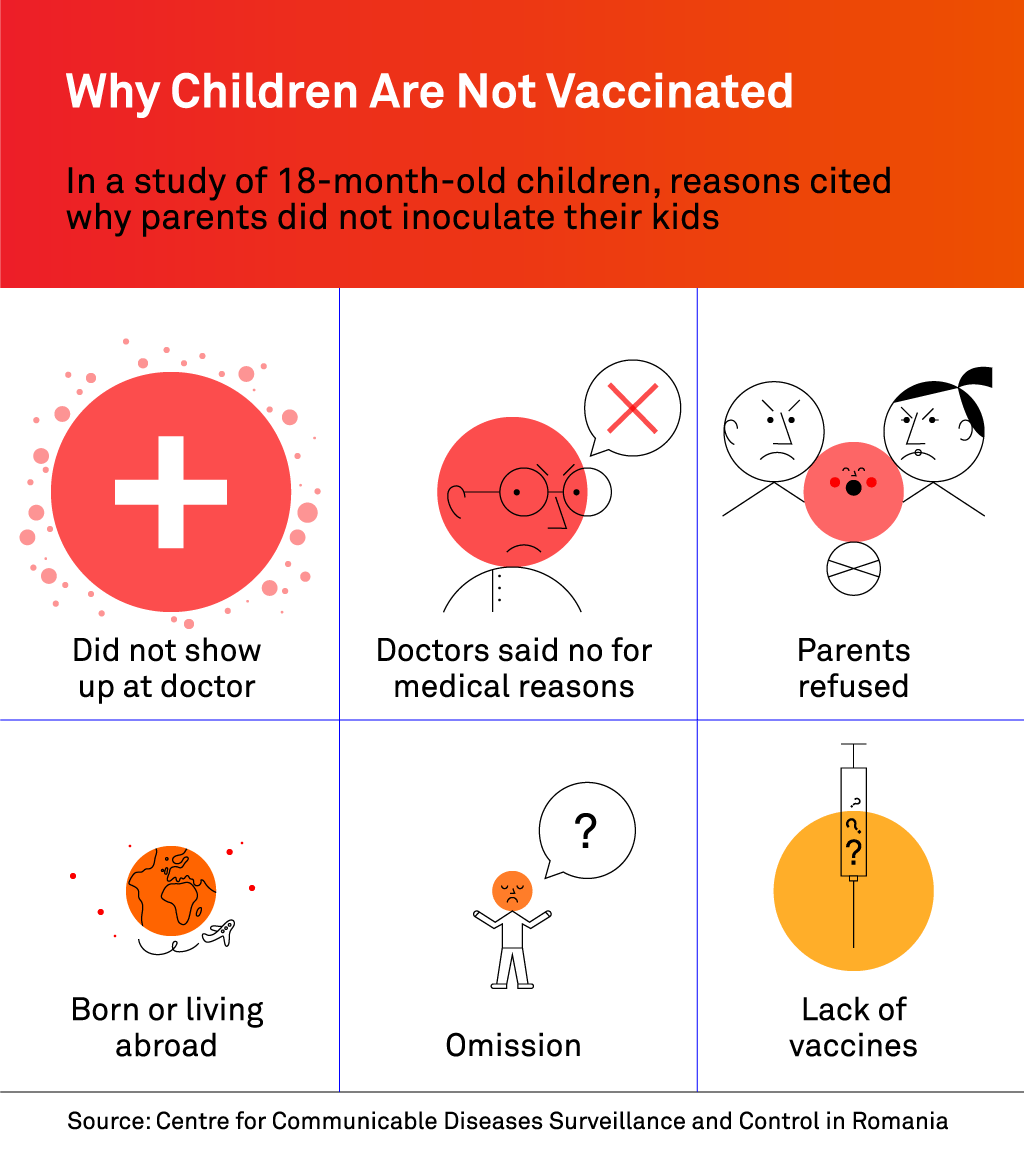

But while the anti-vaxx movement is vociferous, their numbers do not fully explain the fall in vaccination rates over the past decade. In February, the Centre for Surveillance and Control of Communicable Diseases in Romania conducted a study of more than 15,000 18-month-old children that shed light on why some were not being vaccinated. For the 3,690 children who were not properly immunised – almost a quarter of those studied – close to nine per cent had parents who said they were against giving them inoculations, especially MMR jabs.

That was only slightly more than the number of children who were out of the country when it was time to get jabs – and fewer than the 13.6 percent who were advised by doctors not to have shots on medical grounds. By far the biggest group – around 42 per cent – simply “did not show up at the doctor”, suggesting a possible nonchalance towards jabs or lack of faith in health services.

Most people hospitalised with measles in Brasov were from a Roma community 20 kilometres away in the village of Zizin, where local doctor Jan Badan estimates that half of children born in recent years have not been vaccinated. The outskirts of Zizin are full of muddy streets and ramshackle houses with garbage-strewn yards. Some Zizin residents had their own theories about the origins of measles. “Things like this come from the trash,” said Constantin Otelas, a tattooed local councilman who was unsure if any of his nine children had been vaccinated. One young man said he thought the virus had been “thrown from a plane”.

Marcela Taranu, 20, said her unvaccinated six-year-old daughter had caught measles two weeks earlier. She said she had tried to inoculate the girl some time before the measles crisis hit but was told stocks were unavailable. Speaking outside her one-room wooden cabin, she expressed little faith in the authorities’ vaccination drive. “I don’t get it,” she said. “Some did this vaccine, but children from here in ‘gipsyland’ still got the disease.”

Marcela Taranu says she did not vaccinate her daughter because jabs were not available. Photo: © Tudor Vintiloiu

‘It takes only one case’

Romania’s failure to head off the outbreak allowed the virus to spread abroad, but only to places with fertile ground, health experts said. Authorities in Hungary feared measles may have spread across the Romanian border earlier this year when 29 cases were reported in the southeast. A recent outbreak in Serbia raised similar concerns, though authorities are more concerned about cases coming from Kosovo, which is grappling with its biggest spike in measles since conflict ended in 1999. Epidemiologist Predrag Kon from the Belgrade Institute of Public Health said that while the virus found in Serbia had the same B3 genotype as in Romania, authorities had no confirmation that cases came from across the border.

According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, nine EU countries discovered 104 measles cases between them with a probable link to Romania in the year leading up to February 2017: Austria, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Britain and Belgium. “It takes only one case to reignite an outbreak, for the virus to enter a community that is not protected,” said Remy Demesteer, an infectious disease specialist at the Marie Curie Hospital in the Belgian city of Charleroi. “You don’t need illegal migrants to bring diseases with them. Anyone can be a carrier of a pathogen agent [a virus or bacteria].”

Charleroi, one of the biggest cities in the French-speaking Wallonia region of southern Belgium, was at the centre of a measles outbreak that started last December, infecting almost 300 people. The outbreak was traced to an unvaccinated Romanian man who lived in Belgium. He brought the disease back with him after visiting relatives in Romania, according to Carole Schirvel, head of Wallonia’s Unit for Surveillance of Infectious Diseases. The virus quickly spread among relatives, friends and neighbours.

Schirvel said many of those affected were from Romanian or Serbian Roma communities living in the region who fell through gaps in Belgium’s health system because they travelled or did not keep their kids in school. Not registered with doctors, some went straight to emergency rooms, infecting others. Only the polio vaccine is mandatory in Belgium, although nurseries in Wallonia ask parents to give their children vaccines for other diseases too, including measles. “In three or four weeks, everything exploded,” Schirvel said.

“You don’t need illegal migrants to bring diseases with them. Anyone can be a carrier of a pathogen agent.”

Even health workers got sick, accounting for 12 per cent of cases, though there were no fatalities. Measles had become so rare in Belgium that some doctors failed to recognise it, delaying diagnosis. Italy had the worst measles outbreak after Romania, with 4,794 cases – including four deaths – as of early November this year. Epidemiologist Adriana Pistol described a kind of “virus swap” in which measles originated in Italy and then Romanians brought some cases back to Italy.

But for Giovanni Rezza, director of the Department of Infectious Diseases at the Italian National Institute of Health in Rome, the outbreak was a problem of prevention, not migration. Measles vaccine coverage in Italy was around 87 per cent in 2016, according to the health ministry. In the South Tyrol region bordering Austria and Switzerland, it was as low as 67 per cent. The disease disproportionately affected adolescents and adults, reflecting low inoculation uptake in the years following the vaccination’s introduction in Italy in 1976, according to the Italian National Institute of Health.

Research by the institute also shows that the Roma population in Italy was not particularly affected, unlike in past outbreaks. The big surprise was that health workers – more than 300 of them – caught the disease. A study published in March by the Sapienza University of Rome showed that only 38 per cent of medical staff surveyed in and around Rome thought measles jabs should be mandatory for health care workers.

The results angered Giuseppe La Torre, who conducted the study. “If you’re a paediatrician, medical doctor or a nurse involved in intensive care units, in a neonatal intensive care unit, you must be vaccinated against everything,” he said. In response to the outbreak, the government introduced new legislation, passed by the parliament in July, making it mandatory for children to be vaccinated against 10 diseases, including measles, before attending schools and nurseries.

Florentina Marcusan leafs through medical records at her parents’ home in Dubesti. Photo: © Tudor Vintiloiu

In Romania, the prospect of mandatory vaccinations brings little comfort to Florentina Marcusan, the mother who lost her daughter, Karla, to measles. She sometimes goes to Karla’s grave at night with an aching desire to be with her. Other times she says she prays to fall asleep and never wake up again. She said she only knew of the dangers of measles after it was too late. “If I did not know, others should.”

First published on 6 December 2017 on Balkaninsight.com.

This text is protected by copyright: © Octavian Coman. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: A family doctor in Romania vaccinates a child. Photo: © Tudor Vintiloiu.

This article was produced as part of the Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation and Open Society Foundations, in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.