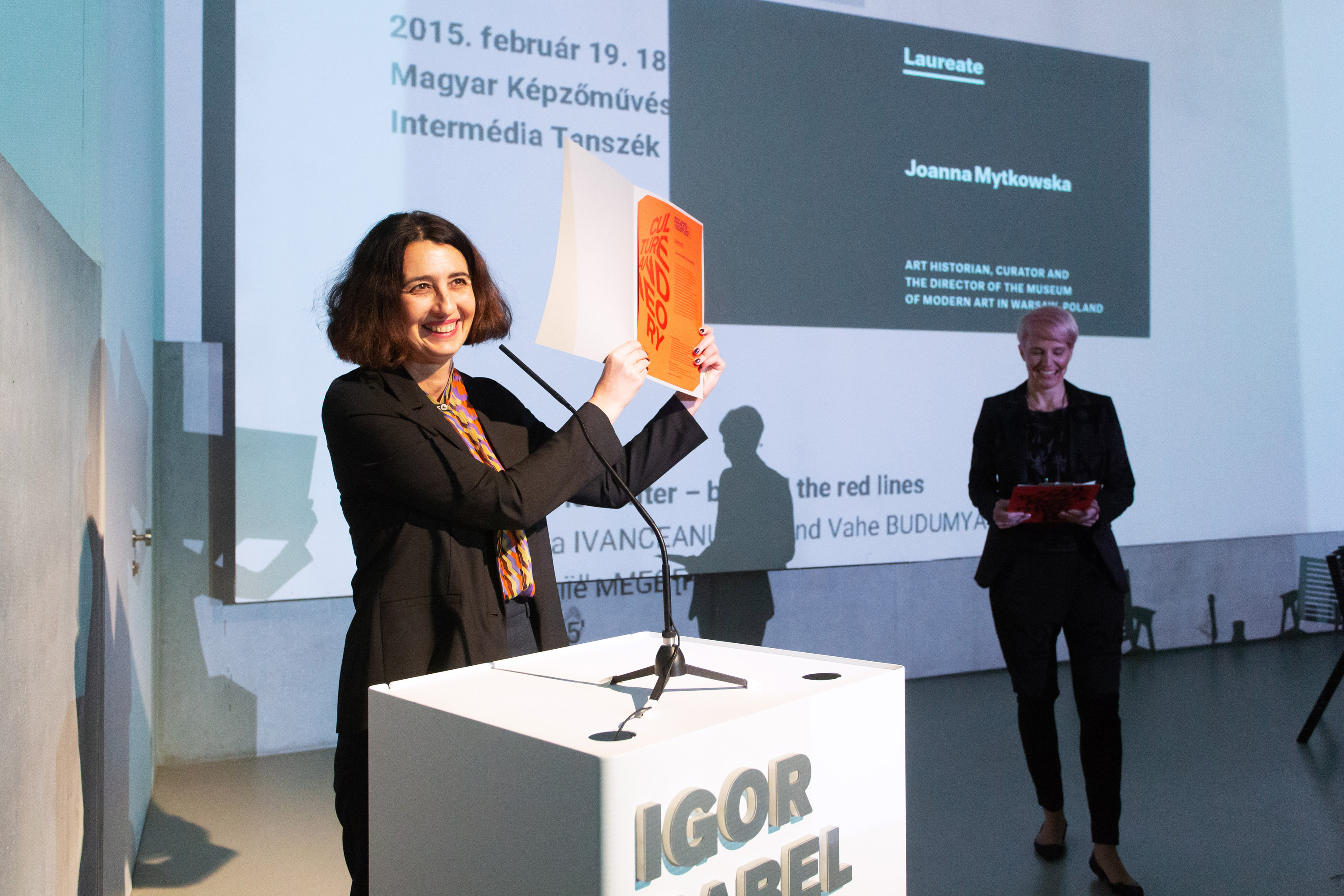

It is society which is at stake for us, not art – says Joanna Mytkowska, director of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. For her extraordinary curatorial and civic achievments as well as her outstanding expertise on art from Central and Eastern Europe she was awarded the Igor Zabel Award for Culture and Theory 2018. In conversation with Marek Beylin she talks about her curatorial practice towards the public, past exhibitions and utopian views.

Let us begin with your experience of Słupsk, a mid-size town where you grew up, located in the formerly German territories near Poland’s western border and inhabited by all sorts of newcomers after the war, so with little native population. How has Słupsk shaped you?

I lived in Słupsk until I graduated from high school. It was indeed a place of migrants, people with no roots. None of the locals had their grandparents there. It was also a young town. My parents, like many others, came there at a very young age with a work order issued by the state. This all translated into a certain enthusiasm for building the new order but also, apart from a small circle of family and friends, into a strong influence of the communist authority. At the same time it meant no conservative pressure – there was no petrified middle class or intelligentsia of the type known from the more traditional cities. The Catholic Church did not have that much of a say either as it was also a “newcomer” in Pomerania. Plus there were none of those ever-patronising “uncles” who always knew better and cherished their ridiculous swords adorning the walls of their apartments. That is not to say that some of our friends would not adopt such attitudes from time to time, but the effect was nothing but grotesque in those blocks of flats in which we lived.

What I took from Słupsk with me, therefore, were egalitarian inclinations and a disregard for social class restrictions. The experience was a fundamental one, something I came to understand years later when I spoke to my colleague, a Brit and then director of an art institution in Sweden, who told me that he couldn’t work in the UK because of his lower-class background. He said that when he spoke to people of the Nicholas Serota type, he felt so aware of the class difference that his accent would automatically deteriorate. It was all so oppressive for him that he decided to work abroad.

Which takes us to the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN) and its policy which, to an extent, is compatible with the experiences you’ve just described. The programme of the MSN, as I see it, is set on a series of axes of conflict: the centre vs. the periphery or semi-periphery, the familiar vs. the strange, and a specified identity vs. one which is a compilation of a multitude of stories about oneself and about the world.

There is also a certain dynamic which my team calls emancipatory. These axes were born out of a fantasy which we now have to revise.

What was this fantasy?

We built it gradually when we started working on the museum, as we did not actually feel bad in the reality we thought we were co-creating. We felt that our role was to mediate and explain the different conflicts. And we soon decided that what was mainly at stake for us was not art but society. We also found out that our initial attempts to revolutionize art, or to cause a change in art, and to communicate with our viewers in such a manner, was a dead-end street – very few were interested in our offer and we found ourselves in isolation.

It was something that I had not cared about before. When working at the Foksal Gallery or at the Foksal Gallery Foundation, both in Warsaw, and later the Pompidou Centre in Paris, I was never involved in audience issues. My task was to make the best possible exhibition, the best possible publication, or to collaborate effectively with the artists. At the MSN, however, it was the first time that I had to communicate with the public.

At one point we managed to break through the “glass ceiling” because art has become for us a modus operandi; it taught us strategy and imagination. It became more of a method of reaching people than a goal in itself. And that is how these axes of conflict that you’ve mentioned were crystallised.

Joanna Mytkowska

Joanna Mytkowska (48) is art historian, curator and, since 2007, the director of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN). She was awarded the Igor Zabel Award 2018. The jury acknowledged “the extraordinary intellectual, curatorial and civic achievements that Joanna Mytkowska has developed over the last 15 years, especially as the director of the MSN in Warsaw. Notable are her exceptional commitment to reaffirming the relation of art to society in times of radical socio-political transformations in Poland and beyond as well as her outstanding expertise on art from Central and Eastern Europe.”

Photo: © Nada Žgank

What strategies, therefore, have you adopted in response to the huge offensive of nationalist populisms that we are now seeing everywhere in Europe and in the US?

Every important artwork has always carried an element of caution. When I look at our collection, which was started in times when nobody took nationalism seriously, since it was just a social niche, I see that many of the artworks had that element of a warning in them.

Before 2015, however, we only saw this as a fragment of the otherwise positive experience of a general change after 1989. At the same time, we presented our Polish transformation as not an isolated case, because such changes were also happening in other parts of the world – leading to similar conflicts. Radical shifts always create a space that is gradually invaded by more tribal ideas and attitudes. We thought that showing such processes via the intimate experiences generated by art would teach us how to be immune to the allure of nationalist or xenophobic ideologies.

For that reason our first large presentations of the collection staged at the old Emilia pavilion [a modernist furniture shop in the centre of Warsaw that no longer exists], i.e. In the Heart of the Country and In the Near Future were filled with examples of how the situation was successfully managed in different places around the world…

It was a truly optimistic view…

Indeed. At the same time, however, there was the exhibition of The New National Art, which was the product of Łukasz Ronduda’s contrariness and the anthropological inquisitiveness of Sebastian Cichocki. The authors of the show presented nationalist ideas clad in contemporary languages of art. This was our first visit to a world which was soon to surround us all.

2015, with all the political changes it brought, came as a shock to us, just as the other developments of recent years have been shocking to many Europeans. We had to settle accounts with our optimism and that of an entire epoch – hence the series of exhibitions beginning with 2016, and in particular Bread and Roses. The show was about how the art world has betrayed its avant-garde roots because artists have quietly moved up the class ladder and are now somewhere up there with their mouths full of empty clichés about the lower classes. No wonder then that these lower classes have no interest in them. A well-known truth it may be, but it doesn’t hurt to remind ourselves of it.

The work by Jacek Adamas was particularly important in this context: a juxtaposition of the Art Forum cover showing Paweł Althamer’s golden airplane with photos of the Smoleńsk plane crash [the 2010 plane crash that killed 96 people, including the Polish president and top state officials]. There was no better way to show just how these two worlds have strayed apart. For too long we believed that the world of the gold people is the true one.

The second exhibition, Making Use, was about post-artistic practices, and about the fact that the emotional field of art is just a small part of its world, which also encompasses the market, institutions and exchange of opinions. It was also about the fact that art can be used by different non-artistic communities and serve other purposes, mainly social ones.

The third show was titled Why We Have Wars, dedicated to modern-day outsider artists whose reasons for making art are different from those of “professional” artists. This was our purgatory.

To this list of exhibitions revising the simple optimism of us all, I would also add the recent show What is Enlightenment?.

That was later, in 2018. The three exhibitions I have mentioned were the emotional and personal reaction to current political developments and also concerned our own professional practices as a cultural institution. What is Enlightenment? was a clinical work and was a call for a universalism in a situation of an acute crisis of values – Enlightenment values included. We drew on the incredible collection of the Print Room of the University of Warsaw Library and set them against contemporary works.

“If we want to have a public impact, we need to move towards less elitist spheres.”

In light of the changes in Poland and Europe we decided to opt for a strategy that we mustn’t stick to our positions, that we should try and erase the divisions instead of building new trenches. On the one hand, our programme is articulated well enough for us to maintain our identity; on the other, however, it is clear that if we want to have a public impact, we need to move towards less elitist spheres. In order to do so, we had to open up to other art languages and develop an even greater sensitivity towards the audience.

The first act in this thinking was marked by the exhibition The Beguiling Siren is Thy Crest, staged in the new, albeit still temporary, seat of the Museum on the boulevards by the Vistula River. It was then that we discovered that difficult issues are more palatable if they use the classical languages of art or artworks. We also discovered that it is necessary to have a clear thesis, just as we did in the exhibition about the Enlightenment. Such a thesis can then be illustrated by means of even the most experimental expressions.

The exhibitions you mentioned present the underestimated world of the margins, the traps of thought and development, as well as of good or bad ideas. However, we do know that if we wish to create a future, we have to have a utopia. Do you, or the Museum, have one?

We did – an optimistic one. However, this image of the whole has been shattered and it cannot be rebuilt overnight. It is why we continue to invite the audience to enter a dialogue with us. This was the aim of the Enlightenment exhibition or the present one, Niepodległe: Women, Independence and National Discourse, about women in the context of independence discourses. This will also be the aim of Daniel Rycharski’s exhibition, for example, an artist negotiating his identity in relation to the Catholic Church. Serious stuff, on a high note.

The exhibition “The Beguiling Siren is Thy Crest” marked a new way of thinking in the artistic strategy of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw to, in the end, develop a greater sensitivity towards the audience to gain public impact. Photo: © Bartosz Stawiarski

Do you see an ambition to create a cohesive image of the whole in contemporary art?

Actually I don’t. What I see is mainly protest. Especially in theatre: do not take our world away from us!

There is a ferment in theatre, I think: if only to mention the appropriation of the national tradition by queer art, thus enriching and broadening the civic content.

It is quite possible that it is the queer community and their expressions which generate the only cohesive image. Mikołaj Sobczak’s works are a good example of that. We do try to be a part of that ferment you mentioned; it was definitely present in the Sirens. Still, these are niche phenomena, while we are striving for a broader audience, with all the difficulties this may entail. Neither do I feel that such ferments, though important, are enough to construct a new project of the future.

Igor Zabel Award

The Igor Zabel Award for Culture and Theory acknowledges exceptional cultural achievements and is awarded to cultural protagonists whose work helps deepen and broaden the international exposure of visual art and culture in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. Since 2018 an international jury selects the laureate and recipients of two working grants based on proposals by ten nominators. The third grant is nominated by the laureate.

The MSN collection includes very many artists from the former Soviet, Central-Eastern Europe. Was this an ideological decision?

We do not choose works for the collection based on regionalisms but on affinities. For example, since we decided to focus very seriously on Alina Szapocznikow, we also bought works by Maria Bartuszová. As we have a very solid representation of Polish neo-avant-garde art, this being our main tradition, we also select similar stances from the region – hence the works by Romanian artist Geta Brătescu. It also strengthens our line of women’s art.

The reason we organised a solo exhibition of Ion Grigorescu, for example, is that we felt his actions were a good explanation of certain attitudes of the likes of Grzegorz Kowalski or Paweł Althamer – radical art submerged in spirituality. So these were precise individual choices.

In other words you do not follow an assumption that there is something very distinct about the region and its art?

Regionality and, especially, the community of experiences are important to me. However, in terms of the transformation experience, it is essential to underline its universal nature rather than the fact that Eastern Europe has gone through it in some kind of extraordinary way. On top of that, there is my reluctance to build an Eastern European ghetto, which was the experience of my youth. I hated the 1999 exhibition After the Wall, where different artists from the region were colonially crammed into a single project.

MSN is building a collection, it produces exhibitions, performances, theatre plays, it organises workshops, presentations, conferences, deals with ideas and social changes. What is this strange profession of curator?

There are many art institutions that work in such a manner now. However, at the beginning of our history at the museum, we were indeed quite hyperactive in this form of activity. There were no curators when I began my professional career, except for one – Hans Ulrich Obrist. We simply helped artists – that was our role. Since I rather quickly jumped into the shoes of an animator of a whole institution, I rarely take on the position of a curator whose function is to manage a project in close collaboration with the artist. My younger colleagues, however, approach this profession with all due seriousness. And they are very open to ever new fields; Natalia Sielewicz, for example, became a dramaturg.

“A museum cannot be just a simple collection of random projects.”

I try to focus on teamwork as only in such a format is it possible to achieve the best results and draw all sorts of satisfaction. It is why we do so many things together, and being a curator is not a priority in our work. At the beginning we didn’t even give the names of the authors of the exhibitions, we simply did them together. We do go back to this idea every now and then as it brings back the feeling of community and stimulates the exchange of ideas. Plus it gives a cohesive line to the museum which, after all, cannot be just a simple collection of random projects.

The Igor Zabel Award for Culture and Theory 2018 went to Joanna Mytkowska, Poland. Igor Zabel Award Grants were given to Edith Jeřábková (Czech Republic), Oberliht Association (Moldova) and The Visual Culture Research Center (Ukraine). Photo: © Nada Žgank

Original in Polish. Translation into English by Ewa Kanigowska-Giedroyć.

This text is published under the Creative Commons License: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. The name of the author/rights holder should be mentioned as followed. Author: Marek Beylin / erstestiftung.org.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Exhibition setting of “A Beast, a God, and a Line” at “The Museum on the Vistula”. Photo: © Daniel Chrobak.