A quarter of a century after conflict, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s population is falling fast — and across all ethnic groups.

lija was angry. Driving his taxi through Sarajevo, the 42-year-old said he had been offered a job as a truck driver in Germany but he needed an extra permit. By the time he had come home and got it though, the job had gone. He had never before wanted to leave Bosnia and Herzegovina but now he was at the end of his tether.

“For 25 years I lived in hope,” he said. “Now I hate myself because of that.” Like so many, he clung on believing that Bosnia would soon become a “normal” country offering decent prospects for the future — but now he has given up and is off to Germany again.

There he will join his brother and sister-in-law and their two children. They told him they would never leave Bosnia, “and then one day they just went”. Ilija’s is the kind of angry rant you can hear every day in Bosnia. And almost a quarter of a century after the end of conflict, the constant reference to a lack of hope is an important clue to explain the parlous demographic situation the country is in.

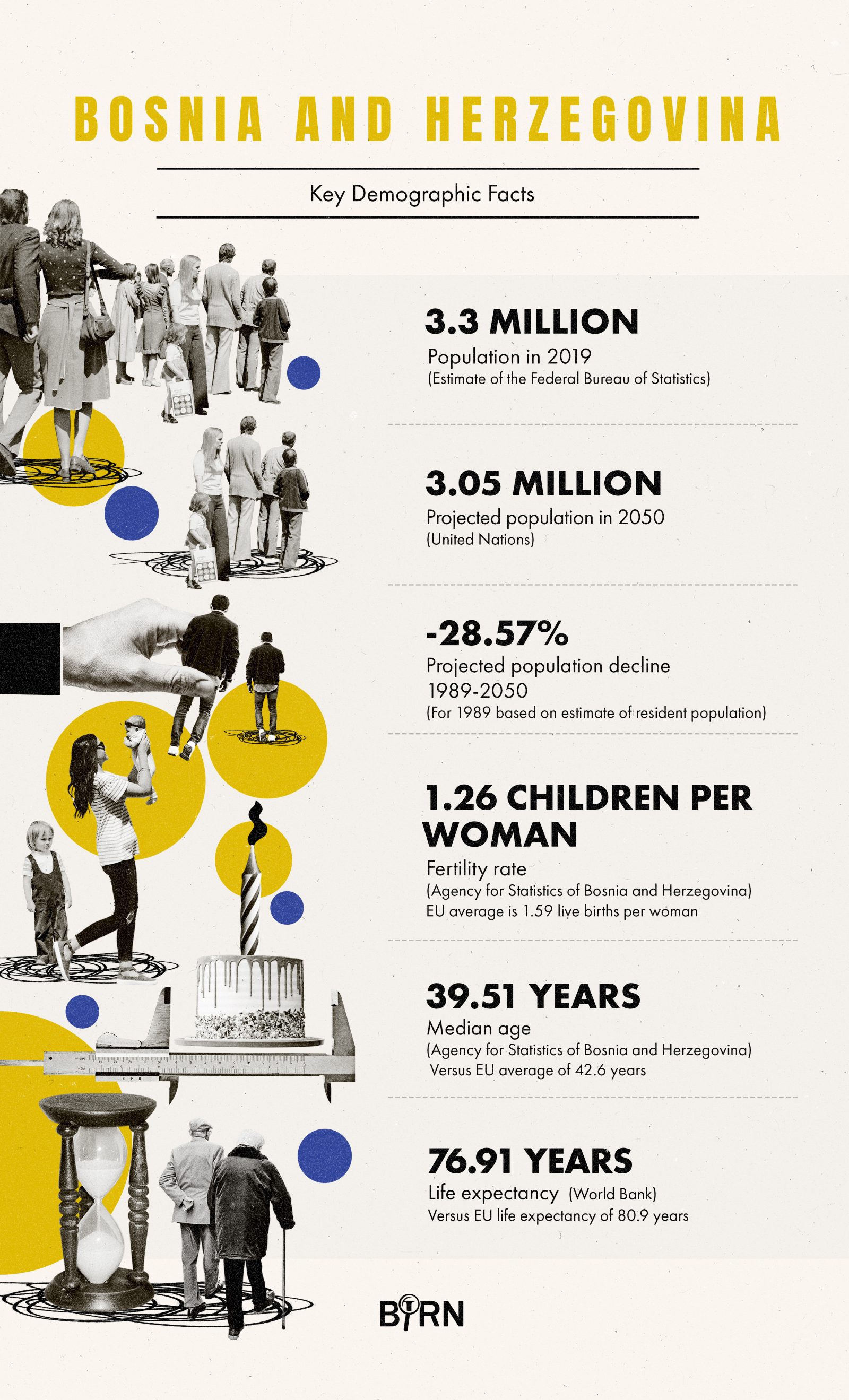

According to the Balkan Public Barometer poll by the Regional Cooperation Council, 68 per cent are dissatisfied with the way Bosnia is heading. In 1991, just before the Bosnian war, there were some four million people in the country. Now there are estimated to be only 3.3 million.

Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

Bosnian women have an average of 1.26 children. That is not only well below the 2.1 needed for a country with no immigration to maintain a stable population, but it is also one of the lowest fertility rates in the world.

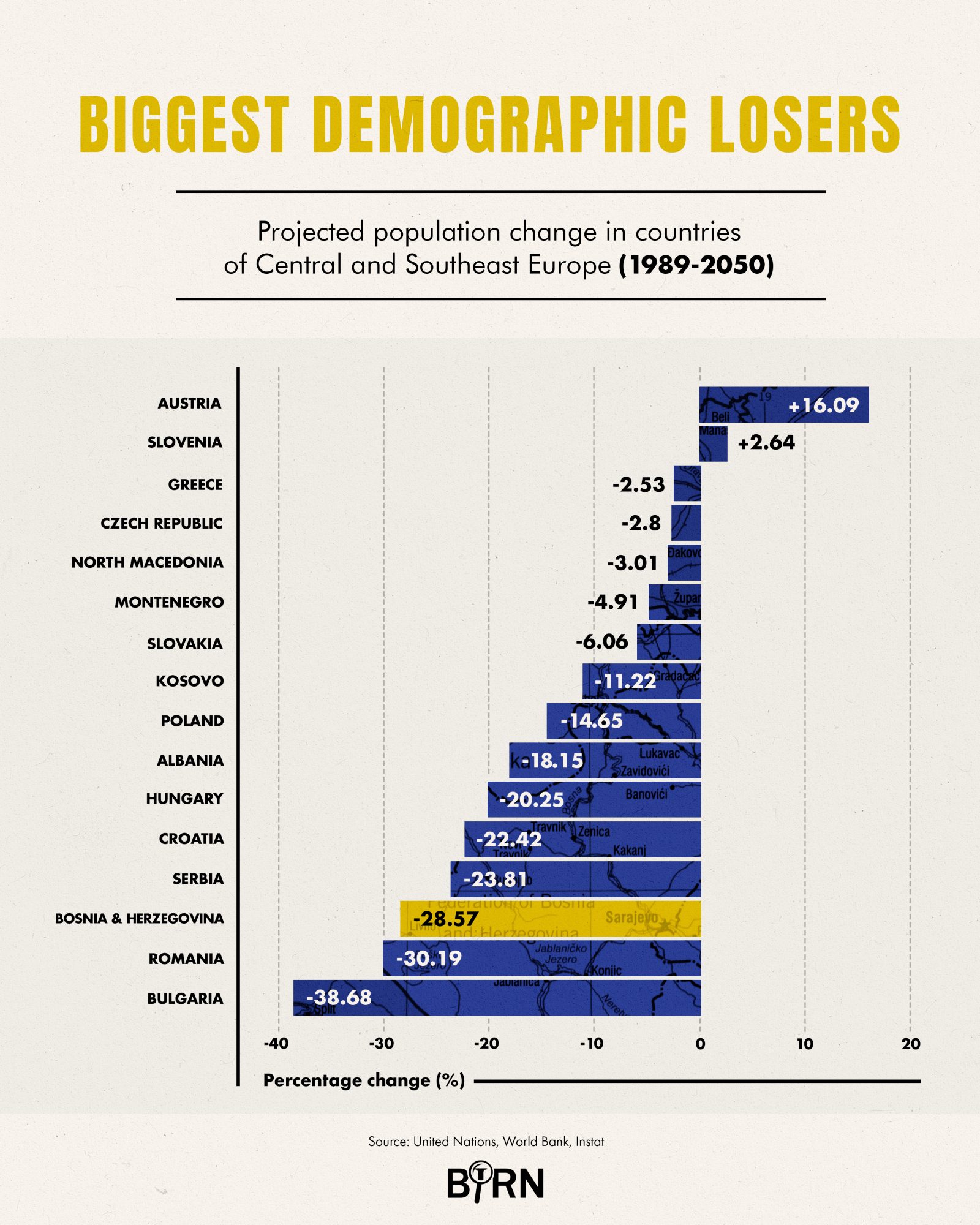

According to the United Nations, unless something changes, Bosnia’s population could shrivel to 3.05 million by 2050, which would be some 29 per cent less than just before the war. However, depending on the rate of emigration, this figure could be reached much sooner.

Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

Until recently, all discussion of demographics in Bosnia was about the numbers and percentages of Bosnia’s Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks and others, but now, while those arguments continue, the entire population is falling, regardless of ethnicity. Unemployment used to be a huge problem, and for many, and in some areas, it still is, but increasingly labour shortages are emerging.

In neighbouring Serbia and Croatia, governments have begun to enact policies to try and address these issues and to encourage couples to have more children. They have little capacity to do so, especially given the enormous appetite for workers in Germany and other Western countries.

Bosnia, with its dysfunctional political system and being poorer than its neighbours, has even less capacity to address its demographic crisis. Everywhere in the former Yugoslavia, getting accurate data is a problem. In Bosnia, the problem is just worse.

Bosnians by Numbers

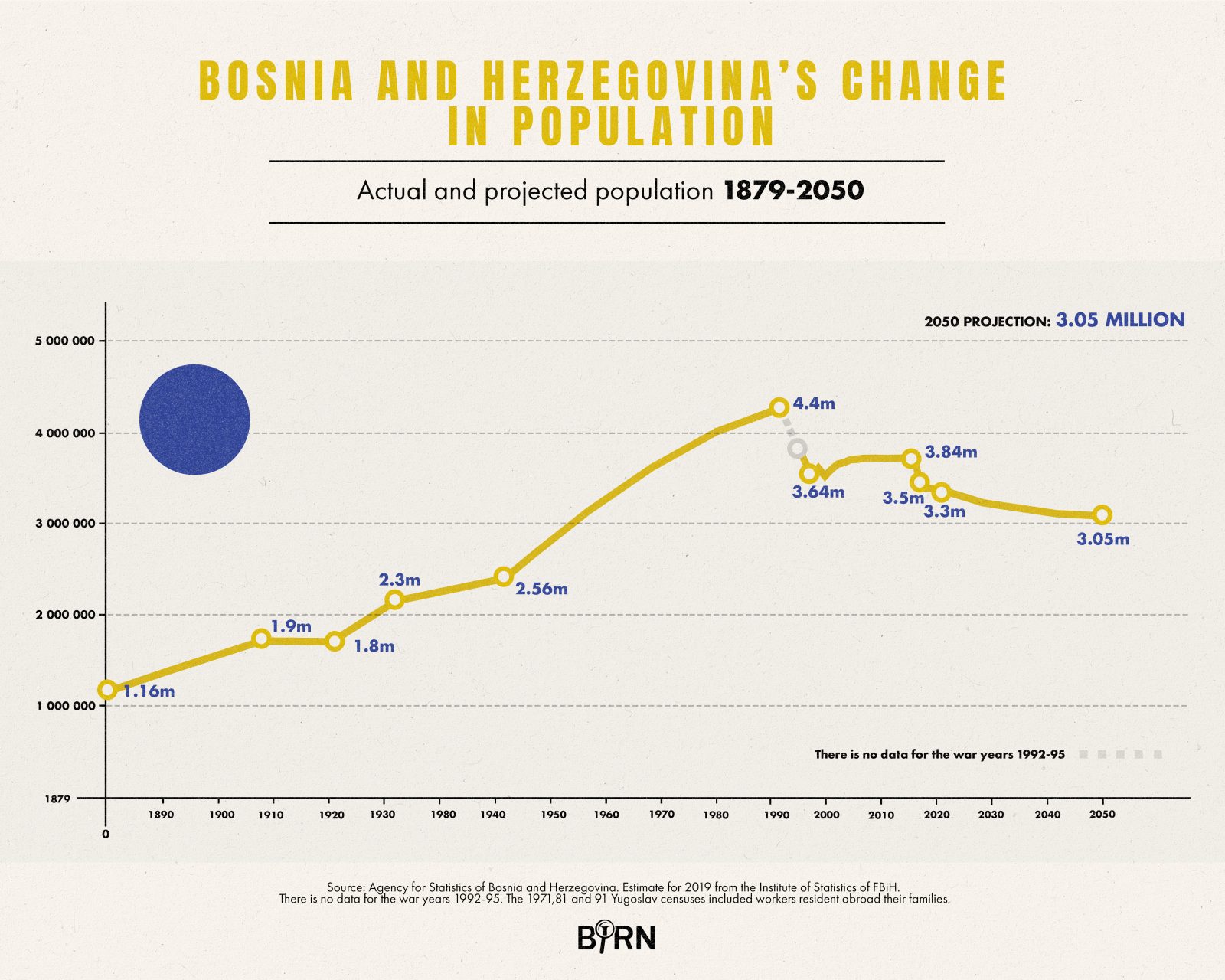

In 1879, there were 1.15 million people in Bosnia.

In 1948, the population was 2.56 million and by 1991 it was 4.37 million, although that number included workers abroad and the real figure could have been as low as four million. An estimated 100,000 died during the 1992-95 war.

Experts believe that 3.3 million is a fair estimate of the current population — but no one knows for sure. Bosnia’s fertility rate is 1.26 children per woman. It has one of the lowest birth rates in the world.

The adapted figure for the 2013 census gave the population of Bosnia as 3.53 million, of whom 2.21 million lived in the Federation, 1.22 million in Republika Srpska and 83,500 in Brčko.

The United Nations estimates that there will be 3.058 million in Bosnia in 2050.

Apart from Croatia and Serbia, large numbers of Bosnians live in Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

According to the latest Balkan Public Barometer, 34 per cent would consider leaving to work abroad. In 2015, that figure was 58 per cent.

In 2017, there were 167,000 people registered in Austria whose birthplace was in Bosnia. On January 1, 2018, there were 95,000 Bosnian citizens registered as living in Austria.

On December 31, 1992, there were almost 20,000 Bosnians registered as living in Germany. This number soared during the war, peaking at 341,000 by the end of 1996. By the end of 2010, it had dropped to 152,000. Ever since, that number has been creeping up again.

At the end of 2018, there were 190,000 Bosnians registered in Germany. There were also 396,000 Croats, as many as 20 per cent of whom could be from Bosnia but using Croatian passports. There were also 216,000 citizens of Serbia.

Bosnians come and go. In 2018, the German authorities registered 25,000 people as arriving from Bosnia to live and work and almost 11,000 leaving Germany for Bosnia.

In the years 2014-18, the Germans registered 119,000 arriving from Bosnia while 68,000 left Germany for Bosnia, so in this period 50,000 in effect left permanently for Germany.

Between 2000-18, there were almost 40,000 Bosnians naturalised as Germans. In 2018, the figure was 1,880. It has been at this level for the last 15 years.

More Bosnians die than are born every year and it has been like this since 2009. In 2016, some 30,183 were born and 36,571 died, which means a natural loss of more than 6,000.

In 1997, a record 48,397 were born and 27,875 died, so a natural increase of almost 21,000. This period of positive increase petered out in 2007.

Throughout the post-World War II period, there was a natural increase of population. It peaked in 1958 when there were around 80,000 more births than deaths and then began to decrease.

The 1971 census was the first in which Muslims/Bosniaks were recorded as having become the most numerous ethnicity in Bosnia, a position Serbs had held in the past. According to the 1991 census, Muslims/Bosniaks were 43.5 per cent of the population, Serbs 31.2 per cent and Croats 17.43 per cent. According to the 2013 census, Bosniaks were 50.11 per cent, Serbs 30.78 per cent and Croats 15.43 per cent.

The final Yugoslav census of 1991 recorded a Bosnian population of 4.37 million. In fact it was far less, possibly around four million, because Yugoslav censuses included workers abroad and their families.

Estimating the current population is even more problematic. Politicians on all sides have an interest in exaggerating the numbers of their community and diminishing those of the others. Bosnia’s statistical agencies also have no capacity to measure the number of people emigrating.

During the 2013 census, Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks in the diaspora, including those in Serbia and Croatia who did not have far to travel, were encouraged to return for the period that data was being collected.

As a result, the initial figure released for Bosnia’s population was 3.79 million but 260,832 people were later subtracted because they were deemed not to be permanently resident.

In this way, the final census figure was declared to be 3.5 million. However, the authorities in the Republika Srpska (RS), the Serbian-dominated half of the country, rejected the census findings.

Damir Josipović, a demographer at the Institute for Ethnic Studies in Ljubljana, has written that “analysis leads us to the conclusion that the official number of population in Bosnia-Herzegovina is overestimated by a large proportion”, and concluded that it could have been as low as 3.3 million in 2013.

Emir Kremic, the director of the Federal Institute of Statistics, and Nermin Oruc, director of CREDI, a social science think tank, both believe, however, that 3.3 million is an accurate estimate for the number of people in Bosnia today.

If the revised 2013 census figure is correct, this would mean that Bosnia’s population has declined, thanks to emigration and more deaths than births, by some 200,000. It is “a joke” to claim, as some non-governmental organisations have done, said Kremic, that this is the number of people who have emigrated in the last three years alone.

A major problem is not only the lack of reliable data but also of conflicting figures. Labour Force surveys show the population of Bosnia to be lower than that estimated by the statistical agencies.

Every conflict, from 1878 to the last war, has seen huge population movements. During the 1992-95 war, some two million were believed to be either displaced within Bosnia or refugees abroad. After the war, large numbers returned, though many not to where they used to live.

Large numbers of Bosnian Croats fled to Croatia and Bosnian Serbs to Serbia while many Serbs fleeing Croatia settled in the RS, thus “compensating” for some its loss in terms of population of Bosniaks and Croats.

While nationalist ideologues celebrated the tidying of the ethnic map, the conflict resulted in huge demographic changes within the country and losses for all — quite apart from the deaths of some 100,000 in the war.

According to Josipović, the war led to the loss of 32 per cent of Bosnia’s Croat population, 25 per cent of its Serbs and 12 per cent of its Bosniaks. Perhaps because the immediate post-war years were ones of hope, the number of births far outweighed the number of deaths.

At first glance, this looks like a post-war baby boom. In fact, if one compares the figures with those of pre-war births and deaths, while the numbers are less than one would have expected if there had not been a war, they correspond to pre-war trends.

The number of births tumbled rapidly a few years after the war though, while the number of deaths increased. In 2016, there were 6,388 more deaths than births.

During the Yugoslav era, demographic figures and ethnic balances shifted in Bosnia. Serbs had historically been the biggest single ethnicity but the 1971 census showed that Muslims (now called Bosniaks) had taken this place.

After World War II, large numbers of Serbs moved from poorer regions to Serbia’s fertile Vojvodina region, from where ethnic Germans had been ethnically cleansed or fled. There was also a trend for Serbs to gravitate for university and work to Serbia while Bosnian Croats went to Croatia and Bosniaks from the Sandžak region straddling Serbia and Montenegro moved to Bosnia.

In the past 25 years, different trends have been at work. As Croatia gives citizenship to Bosnian Croats and anyone else who can claim to be a Croat, large numbers have taken advantage of this.

EUROPE’S FUTURES

Europe is living through its most dramatic and challenging period since World War II. The European project is at stake and its liberal democracy is being challenged from both inside and outside. There is an urgent need from all quarters of state and non-state actors to address the burning problems, both to buttress what has been painstakingly achieved through the political peace project.

From 2018 to 2021, each year six to eight leading European experts are taking up engagement as Europe’s Futures fellows. They create a platform of voices presenting ideas for action whose goal is to reinforce and project forward a vision and reality of Europe. Europe’s Futures is an endeavour based on in-depth research, concrete policy proposals, and encounters with state and civil society actors, public opinion and media.

In the Yugoslav era, many Croats, especially from western Herzegovina, went to Germany and elsewhere for work. After the war, and especially when Croatia joined the European Union in 2013, many Bosnians went initially to Croatia to do the jobs done by Croats now going to Germany.

Bosnians were also an important source of seasonal workers, going to Croatia to work in tourism during the summer, for example. Today, seasonal and circular migration is still important, especially from the RS, but Germany, Slovenia and Austria, with their better pay and conditions, are now the favoured destinations.

Not being a member of the EU made it hard for Bosnians without Croatian citizenship to work in the EU, but recently the demand for labour from several countries has made it far easier to work there legally. Slovene and Croatian agencies also recruit Bosnians, to drive trucks for example, who then work in Germany and elsewhere.

Some find work via Bosnia’s Labour and Employment Agency, which has agreements with Germany to provide nurses and workers of all kinds for Slovenia. In the period 2013-19, more than 5,000 nurses went to Germany under this scheme “and only 20 have returned to Bosnia”, said agency spokesman Boris Pupic.

In the same period, there were just over 47,000 contracts for Slovenia but it is unknown how many of these workers remain there. Of this number, 23 per cent are drivers and most of the rest have various skills needed in the construction industry.

As a result of emigration and falling birth rates, shortages are now emerging of medical personnel and construction workers while schools are closing for lack of pupils. Oruc scoffed that government officials talk of “exporting” labour. He said that it shows their perception that “the more people that we send abroad, the lower the unemployment rate will be, that there will be less pressure on social benefits and more remittance inflows. Presenting this as an achievement and a success bothers me.”

Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

What is happening in Bosnia is best summarised in a cartoon published by Buka, an online news site from RS. In reaction to an RS government discussion about ideas of what to do about emigration and low fertility rates, but with no policies enacted, Buka commented that ministers still did not understand the issues at stake.

The cartoon shows a couple making love, but they are on the floor in a dingy room lit by a candle on a cardboard box. The man wears a patched sock and plaster has fallen off the wall.

People like Ilija are leaving, not just because they can earn more elsewhere, but because they see politicians getting rich while Bosnia remains poor and corrupt and its institutions function poorly if at all. Bosnians went to the polls in October 2018 and its politicians have only overcome wrangling between the three main nationalist parties that had prevented the formation of a state-level government in November 2019.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN or ERSTE Foundation.

First published on 21 November 2019 on Reportingdemocracy.org a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The article was produced within the framework of the Europe’s Futures project.

This text is protected by copyright: © Tim Judah. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures and graphics are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy