Kosovo may be Europe’s newest state but whoever has been in charge has been collecting data for as long as anyone has had the power to collect taxes.

A 1330 charter of the Serbian Orthodox Visoki Dečani monastery in western Kosovo records the number of settlements and households around it and in what is now northern Albania. This appears to show that the vast majority of the people there were Serbs. Not so, argue some Albanian historians who say Serbian officials were “slavicizing” Albanian names in order to assimilate them.

In Kosovo, history has always been war by other means and so it is easier to find detailed analyses of how many Serbs and Albanians lived in Kosovo at any one time in centuries past than it is find to find analyses of numbers, trends and hence the needs of people, rather than Serbs, Albanians and others, who live in Kosovo today. Statistics have been marshalled or massaged to support one side or another, or simply guessed at — all of which makes cogent analysis of Kosovo demographics far more difficult than anywhere else in the Western Balkans.

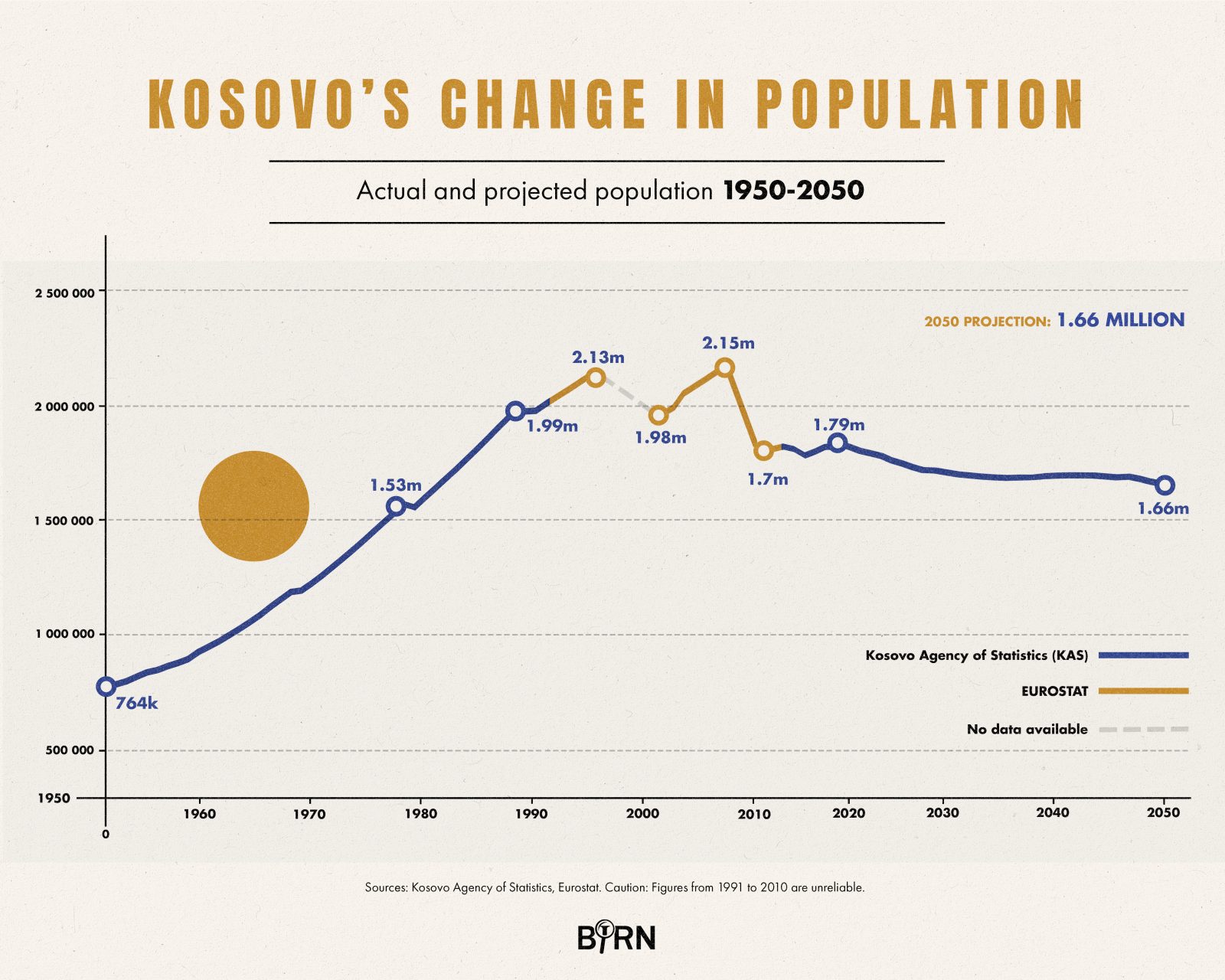

Kosovo’s change in population. Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

For example, according to Eurostat, the EU’s statistical agency, which takes its data from ASK, the Kosovo Agency of Statistics, in 2010 Kosovo’s resident population was 2.2 million but in 2011 it was 1.79 million. So did more than 400,000 people suddenly die or emigrate? Of course not. The explanation behind this statistical cliff helps us understand why politics has made it so hard to know how many people live in Kosovo.

The explanation behind the country’s statistical cliff helps us understand why politics has made it so hard to know how many people live in Kosovo.

In 1981, the Yugoslav census recorded a total population of 1.58 million, of whom 77.4 per cent were Albanians and 14.9 per cent Serbs and Montenegrins. By the time of the next census in 1991, Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević had abolished Kosovo’s autonomy and Albanians boycotted the census, meaning that the Yugoslav Federal Statistical Institute had to estimate their numbers. It concluded that there were now 1.97 million people in Kosovo, of whom 82.2 per cent were Albanians.

In fact, the number actually in Kosovo was less because Yugoslav census figures included those working abroad and their families. According to an estimate the Institute made in 1989, there were actually only some 1.87 million resident in Kosovo.

However, during the 1990s it was common to read that Kosovo’s population was at least two million. When the first post-war census was taken in 2011, it was discovered that Kosovo’s population was far less than anyone thought, which accounts for the jolting drop in the Eurostat figures.

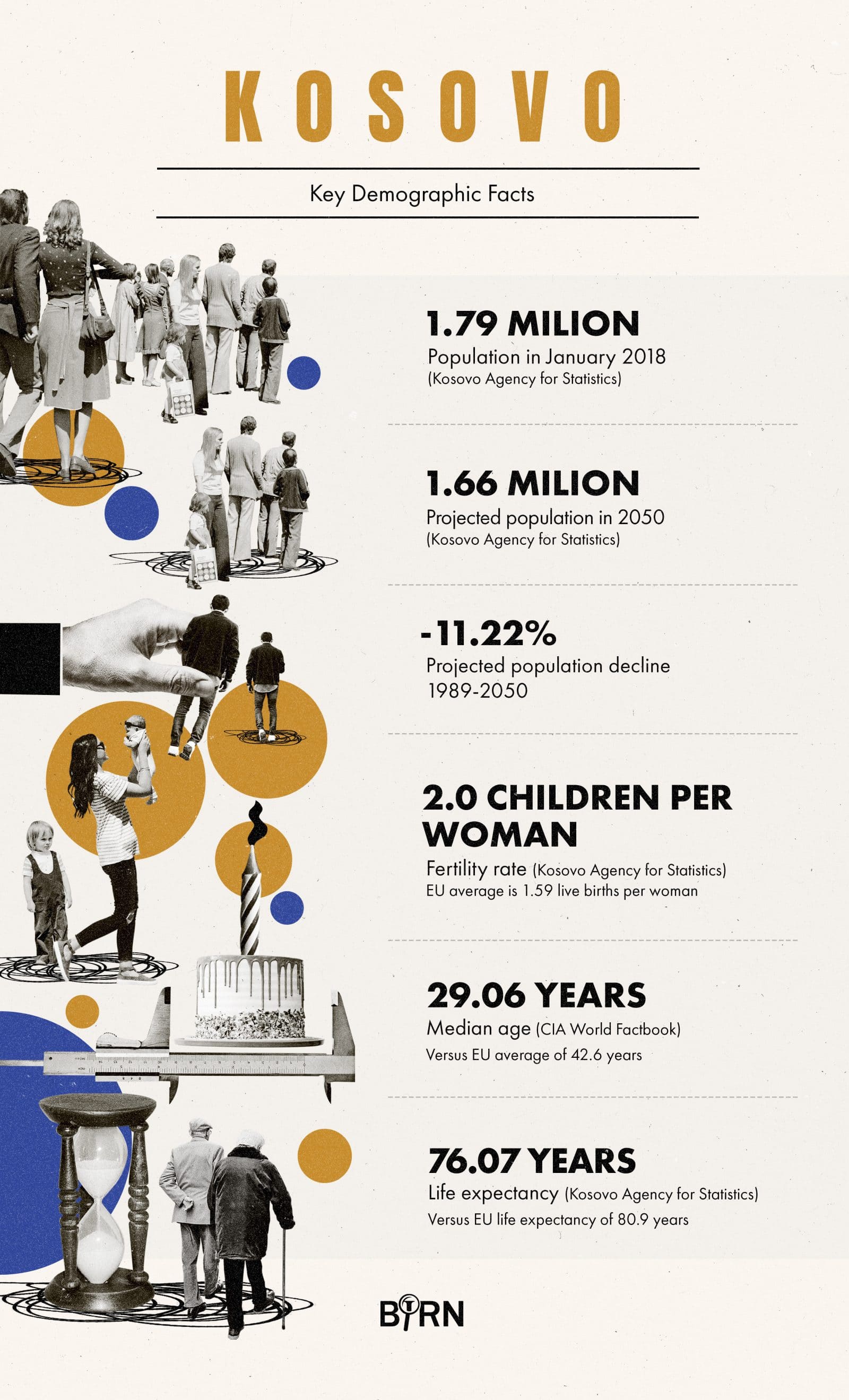

Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

A major reason for the error was a fall in the fertility rate, which throughout the Yugoslav period had been extremely high. In 1950, women had an average of 7.6 children. By 1981, that had dropped to 4.58. By 1991, it was 3.58 and finally in 2015 it dipped below the replacement rate to 2.00 where it remained in 2018. Until the 2011 census, though, projections were made using higher than actual fertility rates.

There were also no accurate statistics on how many people had left, either to Serbia in the case of Serbs or to the rest of the world in the case of Kosovo Albanians. While the 2011 census was the first to give as close to a reliable picture of the Kosovo population since 1981 now Kosovo Serbs boycotted, or the census was not held in the four Serb-controlled municipalities of the north. So ASK had to estimate their numbers.

Today the websites for the four predominantly Serb-populated northern municipalities put their total population at 70,430 but if we exclude students, especially from other parts of Serbia, this number may be exaggerated for political reasons.

Kosovo’s Serb population is ageing fast and shrinking. There are not enough job opportunities for the general population and hence even fewer for Kosovo Serbs, a large proportion of whom do not speak Albanian.

Over the last year, the Serbian and Kosovo presidents have toyed with the idea of an exchange of territory and people, by which the north of Kosovo would be exchanged for the majority ethnic Albanian-inhabited Presevo Valley in southern Serbia (whose Albanians likewise boycotted the last Serbian census). One problem from the Serbian perspective is that if the exchange happens, the majority of Kosovo Serbs would be left in the south — unless the municipality figures were correct. However, evidence from Serbian sources suggests it is not.

School enrolment and Serbian Orthodox Church figures point to a resident Kosovo Serb population of about 100,000, with about 40 per cent living in the north and the rest in the south. If the suspicion that north Kosovo population figures have been put to the service of political ends is correct, it would not be the first time in recent history.

At the same time, large families needed land and houses and this population pressure meant that large numbers of Serbs sold theirs to Albanians and left for Serbia where the money could buy them far more than they had had in Kosovo.

In the aftermath of the war in 1999, when Serbs fled ethnic cleansing, Serbian officials claimed that around 220,000 Serbs had come to Serbia, which would mean more than actually lived there, according to the 1991 census in which Serbs and Montenegrins participated and which recorded 215,346 of them plus 42,806 Roma, many of whom also suffered at that time. In fact, close analysis by the European Stability Initiative think tank found that the true figure of those who had fled was about 65,000.

At the time, UN agencies used Serbian figures, giving them credibility. Today, Kosovo’s Serb population is ageing fast and shrinking. There are not enough job opportunities for the general population and hence even fewer for Kosovo Serbs, a large proportion of whom do not speak Albanian.

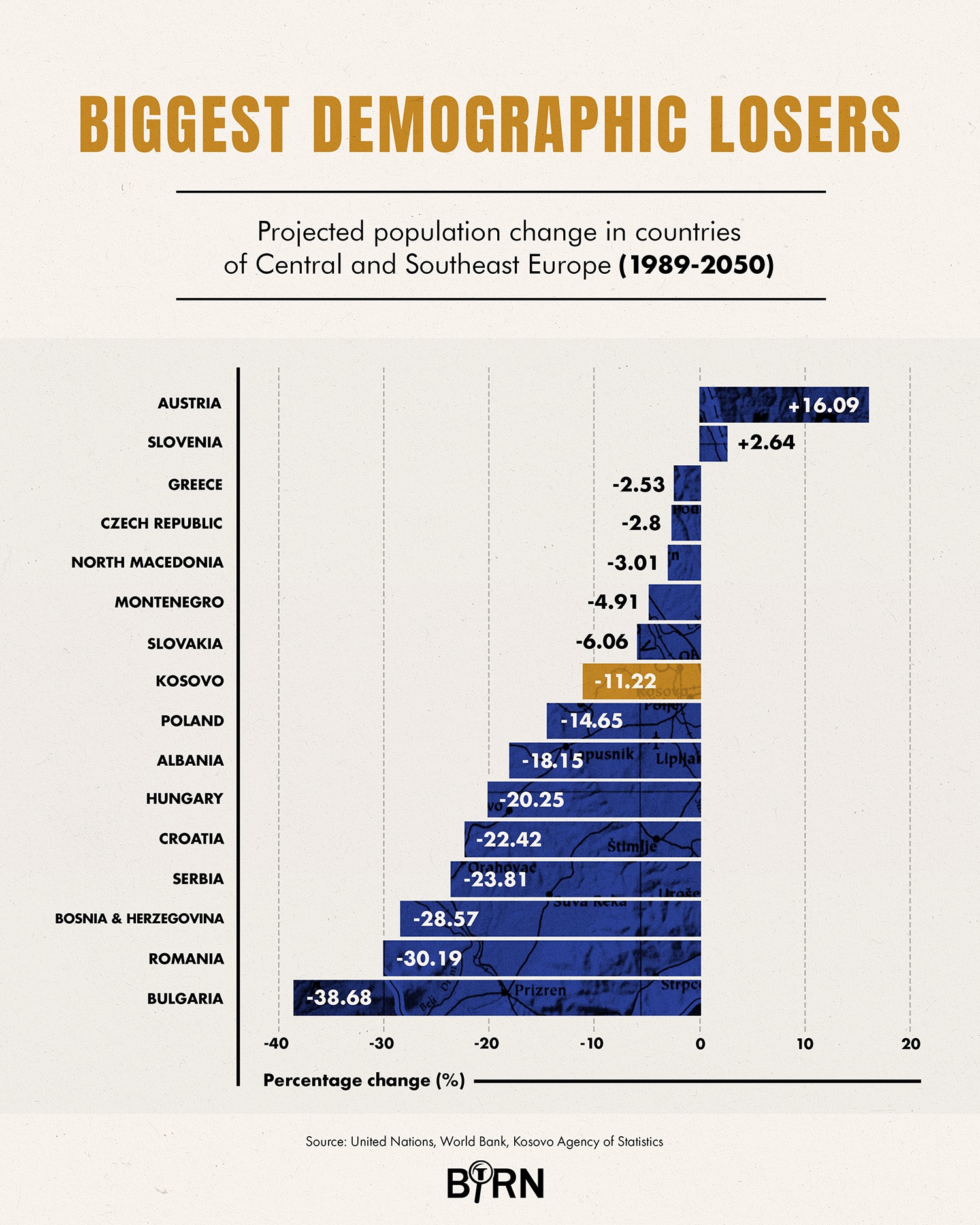

Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

Across the Balkans, the trends point to ageing and shrinking societies from which the young and skilled are emigrating in large numbers. Today, thanks to its population explosion, especially in the 1980s, Kosovo has the youngest population in Europe. But now that its birth rate has dipped below the replacement level, and thanks to emigration, Kosovo’s Albanian and hence entire population has begun to age and shrink too.

According to ASK analysis, Kosovo’s population could fall to 1.49 million by 2061. In 2017, 25 per cent of the population was 14 years old or below and eight per cent was 65 years old or above. By 2061, there may be just 13 per cent in the youngest age bracket but 27 per cent in the older one. The question of emigration is a vexed and politicised one. It is also one that is hard to enumerate because of a lack of data.

Today, thanks to its population explosion, especially in the 1980s, Kosovo has the youngest population in Europe.

In the Yugoslav period, there were three main flows of emigration: Kosovo Albanians and Serbs who went to work abroad as so-called gastarbeiters, Kosovo Serbs who went to Serbia and Kosovo Albanians who went to other parts of Yugoslavia. The destruction of Yugoslavia closed off legal emigration apart from those seeking asylum. In the period 2013-16, the number of economically motivated asylum applications in the EU from Kosovars plus those detected illegally in EU states was a massive 229,005.

EUROPE’S FUTURES

Europe is living through its most dramatic and challenging period since World War II. The European project is at stake and its liberal democracy is being challenged from both inside and outside. There is an urgent need from all quarters of state and non-state actors to address the burning problems, both to buttress what has been painstakingly achieved through the political peace project.

From 2018 to 2021, each year six to eight leading European experts are taking up engagement as Europe’s Futures fellows. They create a platform of voices presenting ideas for action whose goal is to reinforce and project forward a vision and reality of Europe. Europe’s Futures is an endeavour based on in-depth research, concrete policy proposals, and encounters with state and civil society actors, public opinion and media.

Now, a new chapter is opening, which is that while people from Kosovo remain without visa-free travel to the Schengen zone, countries like Germany and Croatia have begun to give work permits to them in ways and numbers that they did not before.

Today, while we can rely on the statistics of foreign countries to number Kosovo citizens in them, we can only guess at the size of the diaspora, though it is commonly said to be around 700,000 in Europe, with a small number in North America and elsewhere.

That figure only refers to Kosovo Albanians though, and while the number of Kosovo Serbs outside of Kosovo and Serbia will be small, the number of those born in Kosovo and their children in Serbia would not be.

Anyone who was born in Kosovo or has one parent who is registered as a citizen can claim Kosovo citizenship and vote.

In 2018, the number of people from Kosovo in Switzerland was 111,826, in Germany 218,150 and in Austria 25,025. In the period 2010-18, the number of people from Kosovo who received Swiss citizenship was 25,311 but in the years before that large numbers who were citizens of Yugoslavia or Serbia also received it and it is impossible to tell from those figures who was from Kosovo or who was a Serb or Albanian. Germany only began recording naturalisations of people from Kosovo from 2008, and from then to 2018, the total number is 33,966.

Given these numbers, it is quite possible that the total diaspora in Europe, including children with foreign citizenships, is about double the recorded numbers of Kosovo citizens abroad, so indeed about 700,000 people. According to the International Monetary Fund, diaspora remittances represented 11.8 per cent of gross domestic product in 2018. The median age in Kosovo is 29.06, while in Albania it is 36.07 and Serbia it is 43.

Kosovo should benefit far more than it does from its young population but the lack of jobs and opportunities remain an obstacle to growth and a spur to emigration. The trends are clear though. Kosovo is years — a couple of decades even — behind the rest of the Balkans when it comes to ageing and population shrinkage, but unless something changes, it is moving in exactly the same direction as its neighbours.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN or ERSTE Foundation.

First published on 7 November 2019 on Reportingdemocracy.org, a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The article was produced within the framework of the Europe’s Futures project.

This text is protected by copyright: © Tim Judah. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures and graphics are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy