The EU’s youngest member state has a history of unrelenting depopulation and successive governments have failed to solve the problem.

It is a hard sell persuading Croatia and the world that when it comes to demography, the news is good. But that is what Ivica Bosnjak, assistant minister in charge of demography at Croatia’s Ministry for Demography, has to do. According to Bosnjak, emigration from the country peaked last year and an increased number of births in 2018 heralded some really good news.

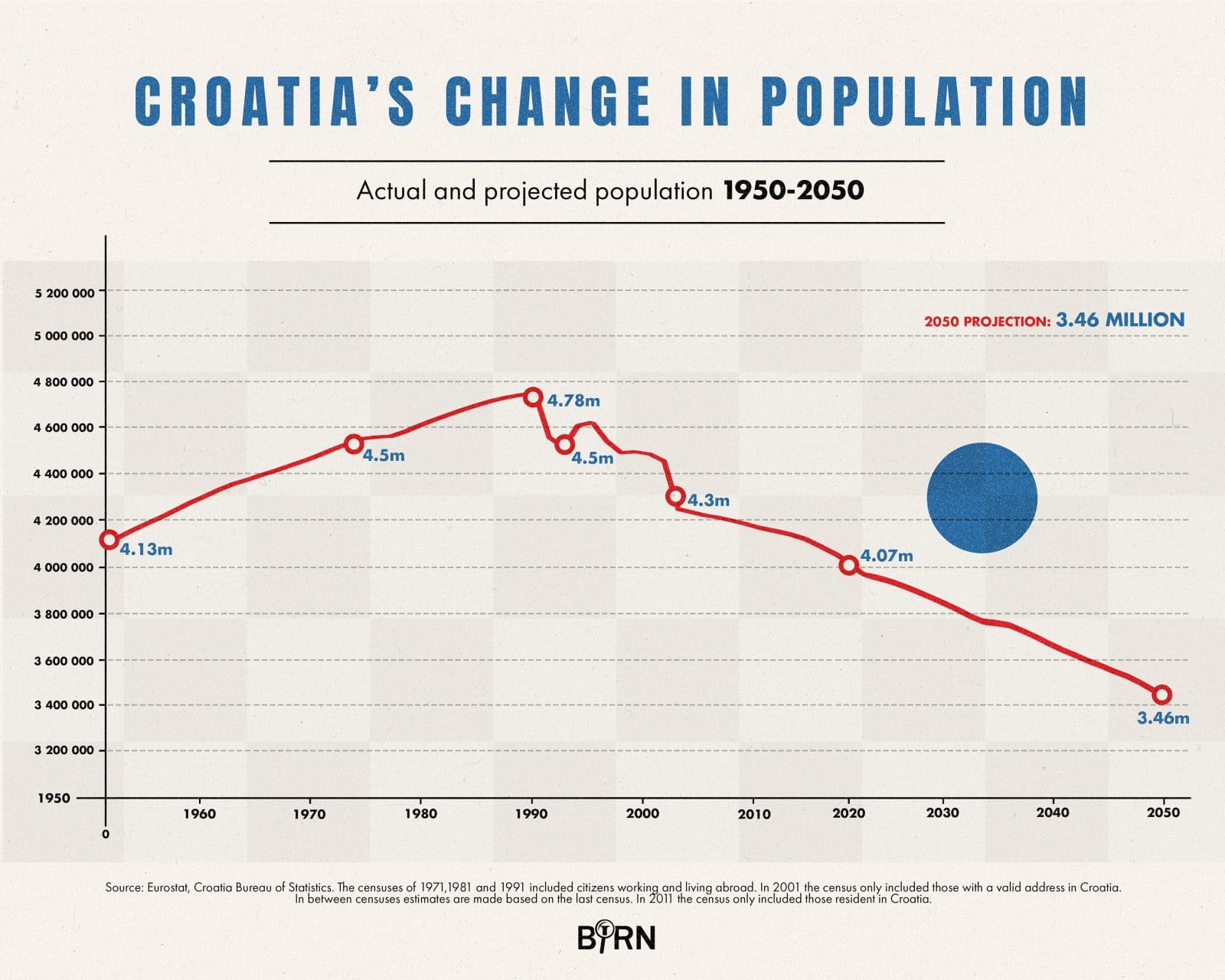

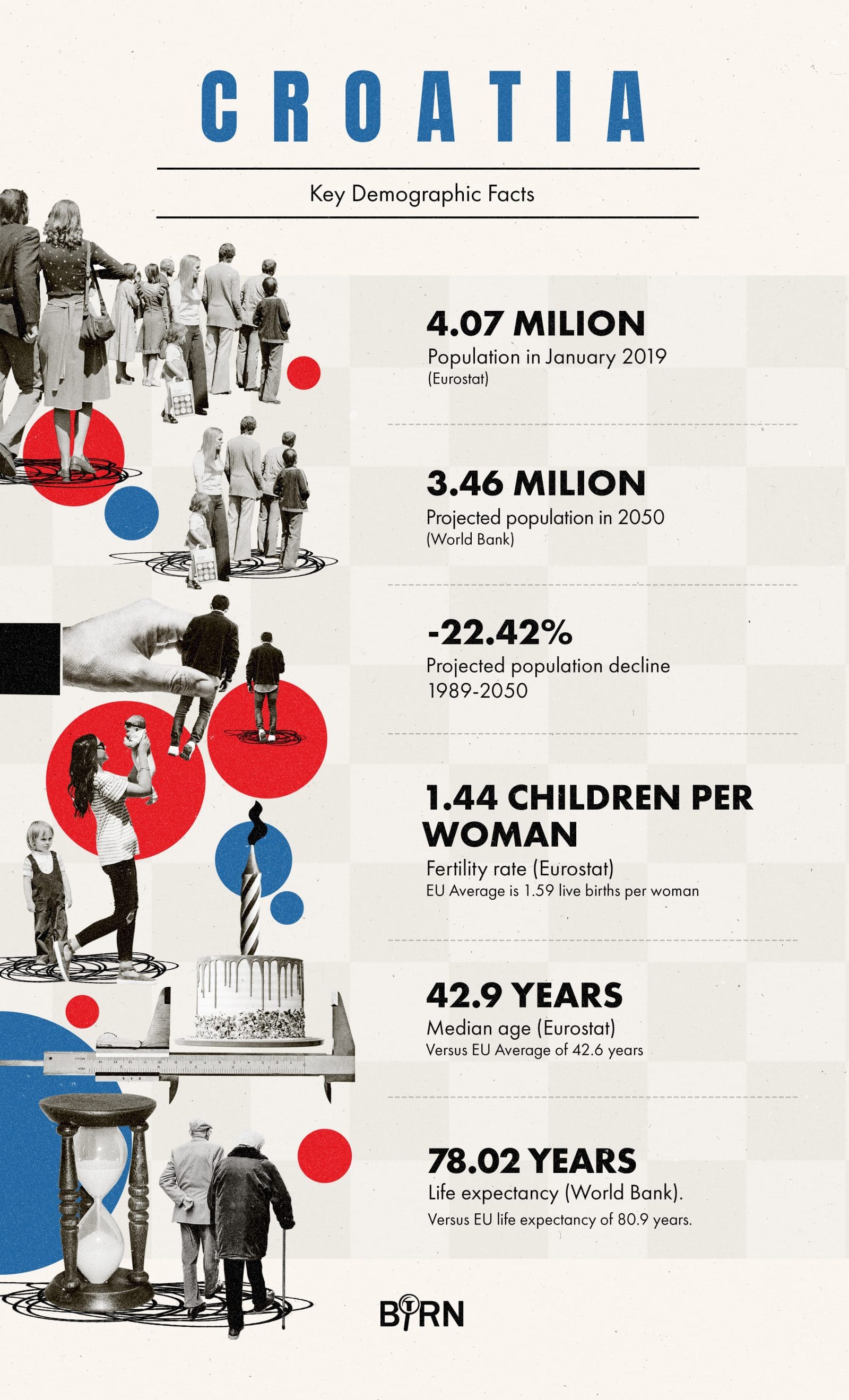

In 2020, Croatia’s demographic decline will stabilise and from then on, government policies will lead to an increase in population, he said. No one has a crystal ball to predict the future but the hard data from the past tells a story of unrelenting demographic decline. According to Eurostat, the EU’s statistical agency, which bases its numbers on data it receives from member states, at the beginning of 2019, Croatia’s population was 4.07 million. That is the lowest it has been since 1957.

Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

Kresimir Ivanda, a leading demographer at Zagreb University, believes that today’s true figure is even lower and is actually 3.95 million. In 1960, the population was 4.14 million, according to the Croatian Bureau of Statistics. It increased every year until 1991 when, according to the last Yugsoslav census, it peaked at 4.78 million. In fact, in common with the rest of Yugoslavia, this figure was boosted by including non-resident gastarbeiter and their families.

According to research by Damir Josipiović of the Institute of Ethnic Studies in Ljubljana, Slovenia, the real number of people who actually lived in Croatia in 1989 was 4.46 million. According to the Croatian Bureau of Statistics, it was 4.51 million. The wartime period saw an outflow of Serbs from Croatia and an inflow of some 200,000 Croats from Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ever since, Croatia’s population has continued to shrink thanks to its low birth rate and its ageing population. Croatian women have an average of 1.44 children, which is not only below the 2.1 needed for replacing a country’s population, but the second-lowest of all the seven post-Yugoslav states.

Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

In 2018, almost 37,000 babies were born in Croatia, almost 400 more than in 2017 — though hardly a big enough increase to be considered an upward trend, according to Bosnjak. And 2017 was the worst year on record since 1960. Then, 76,156 babies were born in the republic. Even in 1992, that is to say the year after the worst year of the war in Croatia, 46,970 births were recorded, a figure that presumably excludes most of those born in the then Serbian-breakaway areas.

Successive Croatian governments have tried to tackle the demographic problem but so far with no success. A Demographic Revival Council was founded in 2017 to coordinate ministerial policies. A new strategy for halting and reversing Croatian decline is being prepared to replace a national population policy from 2006. Bosnjak said huge sums were being invested in everything from kindergartens to agriculture, especially in areas that have been depopulating over the last quarter of a century, such as the east of the country.

EUROPE’S FUTURES

Europe is living through its most dramatic and challenging period since World War II. The European project is at stake and its liberal democracy is being challenged from both inside and outside. There is an urgent need from all quarters of state and non-state actors to address the burning problems, both to buttress what has been painstakingly achieved through the political peace project.

From 2018 to 2021, each year six to eight leading European experts are taking up engagement as Europe’s Futures fellows. They create a platform of voices presenting ideas for action whose goal is to reinforce and project forward a vision and reality of Europe. Europe’s Futures is an endeavour based on in-depth research, concrete policy proposals, and encounters with state and civil society actors, public opinion and media.

While births and deaths can be tracked exactly, it is far harder to work out how many people are emigrating.

In 2018, the Croatian National Bank published a groundbreaking study that examined how many Croats had gone abroad by looking not at Croatian data but at statistics such as social security numbers in 10 core EU countries.

According to this, some 230,000 people went to those countries between 2013, when Croatia joined the EU, and 2016. Relatively few are believed to have gone elsewhere.

Both Ivanda and Bosnjak agreed with that ballpark figure, though there is debate about how many Croats who show up in statistics abroad are actually from Bosnia, since Bosnian Croats are eligible for Croatian passports.

Some 20 per cent of Croats abroad are believed to be from Bosnia.

The Croatian National Bank study found that 71 per cent of those who had gone abroad were in Germany, eight per cent were in Austria and seven per cent in Ireland.

The numbers who have gone abroad permanently since Croatia joined the EU represent five per cent of its population. A large proportion of them are young, of child-bearing and of working age.

Increasingly whole families have departed. There is no significant immigration to Croatia. Of the roughly 10,000 a year who do come to live in the country, the largest proportion are Croats who have worked abroad who are now retiring and a small number of Bosnian Croats.

The government hopes that measures such as making pension contributions for mothers on maternity leave will help push the fertility rate back up to 1.6 in the next couple of years. But a big problem is the nature of women’s employment. In Scandinavia, which has higher levels of fertility, women tend to work in good jobs in health care or education but in Croatia hundreds of thousands of women work in badly paid and insecure jobs in retail, Ivanda said.

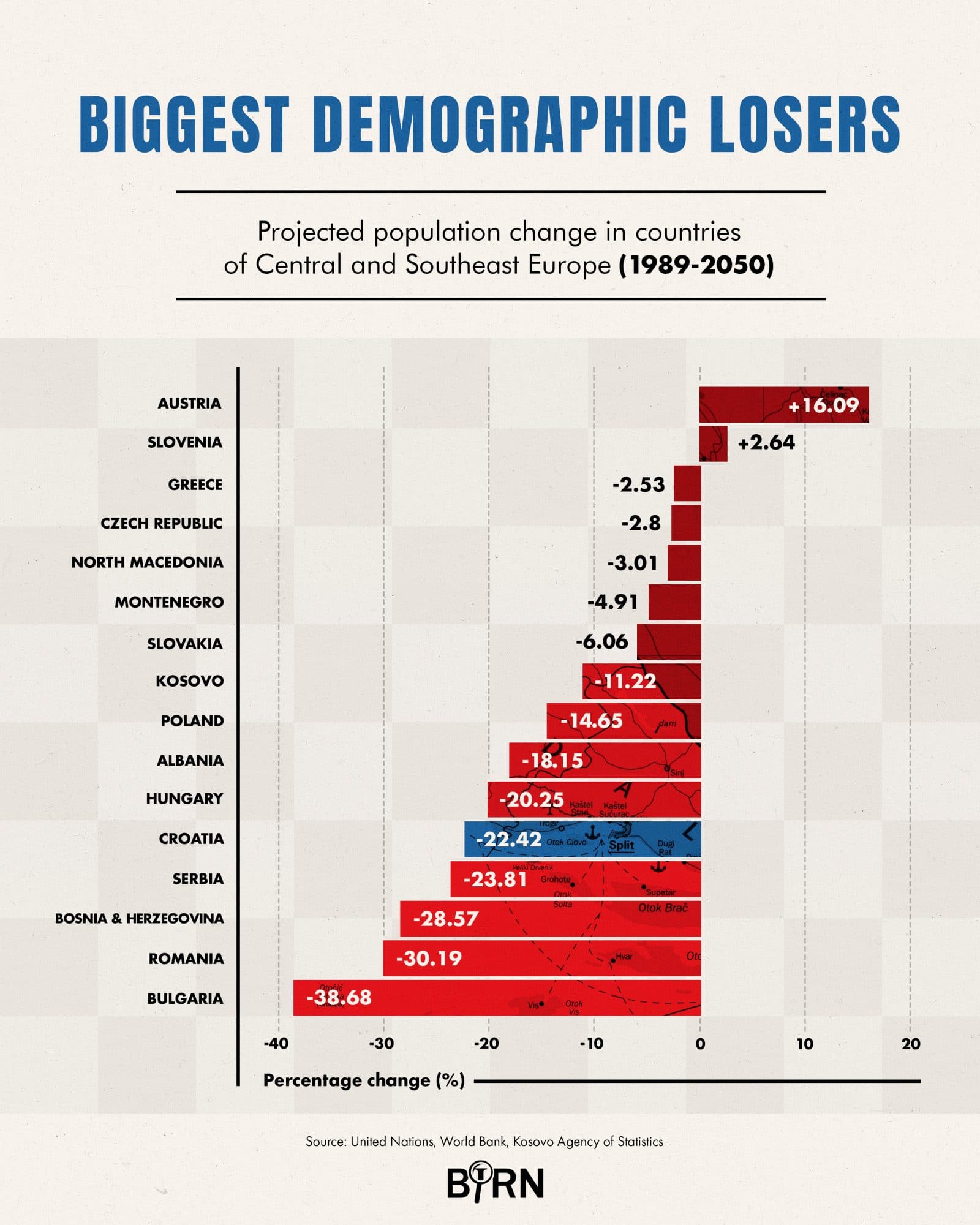

If they go off to have a baby, the likelihood is that their jobs will not be there when they return, so many do not, especially after a first child. The demographic problems faced by Croatia are shared by other countries in the region, Ivanda said. “This is a new phenomenon and there is nowhere else in the world which has such a high emigration rate and such a persistent low fertility rate.”

“This is a new phenomenon and there is nowhere else in the world which has such a high emigration rate and such a persistent low fertility rate.”

In the past, however, major waves of emigration were offset by high birth rates. Croatia’s fertility rate slipped below the replacement rate way back in 1968, but in the period after that, being one of the richer parts of Yugoslavia, it attracted immigrants from the rest of the country. The demographic crisis and emigration are already causing labour shortages in the seasonal tourism industry and in construction. This year, the government doubled the amount of work permits for foreigners to 63,900 compared with 39,000 in 2018.

In the past, many of these jobs were filled by workers from other parts of the (non-EU) former Yugoslavia but now, as Germany and others have opened their labour markets to them, they go there for well-paid, full-time jobs rather than poorly paid seasonal ones in Croatia. In the longer term, even if a good proportion of those emigrating return, Croatia will still need immigration if it wants to reverse population decline. A UN study predicts that Croatia’s population will fall to 3.46 million by 2050.

Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy.

Bosnjak said the government was formulating a policy that envisages filling empty houses in depopulated areas with settlers from the Croatian diaspora and countries that already have ethnic minorities in Croatia. He mentioned Ukrainians as a prime example. Why a poor Ukrainian would go to live in an area not deemed worth living in by an emigrating local rather than richer Poland or Germany is unclear. Also, Croatia’s largest single minority are overwhelmingly Serbs. Asked whether those who left in the wake of the war, or their children, might decide to come back given the inducements being planned, he said he thought it was unlikely.

Bosnjak said that increasing job opportunities and above all a high quality of life in Croatia would attract those already abroad to return. Ivanda noted, however, that many young people go abroad, especially from depressed areas, because they do not have faith in the future and they believe connections and luck are more important for their future than skills and knowledge. He is not so optimistic about the future himself. In demographic terms, he said, Croatia is not heading “for some big breakdown or crisis” but rather “long-term stagnation”.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN or ERSTE Foundation.

First published on 31 October 2019 on Reportingdemocracy.org a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The article was produced within the framework of the Europe’s Futures project.

This text is protected by copyright: © Tim Judah. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures and graphics are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Illustration: Illustration © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy