Romania has the worst record for unfair trials in the European Union. With the justice system mired in controversy, ordinary victims of judicial errors face an uphill struggle.

When police surrounded his home on a crisp January morning, Petrică Manolachi knew it was all over. The 29-year-old handyman had been in hiding for the past six years, unable to face returning to prison for a robbery he did not commit. But now officers were entering his home in the northeastern Romanian city of Iaşi, pushing away his girlfriend and crying baby, slapping on handcuffs. “I just couldn’t believe you could be arrested for something you didn’t do,” recalled Manolachi, now 39. “It was like in the movies when someone is fighting justice.” That day in the winter of 2010 was the nadir of a struggle that Manolachi says stole his best years — and continues to consume him as he battles for compensation in a country with the worst record for unfair trials in the European Union.

Romania outdoes all 27 other EU member states when it comes to violations of the right to a fair trial and other lapses of due judicial process, as determined by the European Court of Human Rights, ECHR. Outside the European Union, only Russia, Turkey and Ukraine have more dismal records, according to the latest figures from the court in Strasbourg, which has jurisdiction over 47 countries that are members of the Council of Europe. Judicial fairness is a fraught topic in Romania, where the ruling Social Democratic Party, PSD, has been promoting sweeping legal reforms since mid-2016 that it says are crucial to make judges and prosecutors more accountable for miscarriages of justice. The reforms include the creation of a special unit to investigate crimes by judicial staff and new powers for the justice minister to appoint chief prosecutors. But most members of the judiciary and many international observers say the changes are more about curbing the independence of courts than protecting the rights of ordinary Romanians. The reforms come after years of high-profile prosecutions of senior public officials on corruption charges.

As the reforms divide the country, fair trial advocates say the controversy is distracting from actual flaws in the justice system, from rampant wrongdoing by police investigators to poor quality state-funded legal aid and a courtroom culture in which the accused are too often presumed guilty until proven innocent. Injustices are sometimes compounded by long periods of detention for people awaiting trial, even for minor crimes, and errors by overstretched judges with little time to weigh up evidence, critics say. Romania has no jury trials so judges bear full responsibility for delivering verdicts. Remus Budai, a prosecutor at the General Prosecutor’s Office in Bucharest, used a sporting analogy to describe how it sometimes feels to work in a justice system that is far from perfect. “When you watch football on TV, you see where the referee is wrong,” he told the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, BIRN. “But if someone gives you the whistle, you don’t always know what to do with it.”

Petrică Manolachi sits on a bench in Iaşi. Manolachi is fighting for compensation for a life he says was shattered by wrongful conviction. Photo: © Lorelei Mihala

“No chance“

Driving through the streets of Iaşi in his beloved vintage Rover, carefully turning the steering wheel with black leather gloves, Manolachi recalled how all the problems of the legal system seemed to conspire against him. His nightmare began in 2002 when he was 22 and had recently finished compulsory military service. One day, police summoned him to the station to answer questions about a local crime. Three men had allegedly come to the door of an 80-year-old woman, pretending to be collecting money for the church. Two entered her home and seized cash and jewellery. Manolachi spent three days in a police cell, where he refused to give a statement until a lawyer eventually came.

He says four officers hit him. His parents took that allegation to the Military Prosecutor’s Office, which oversees complaints against police, but prosecutors said there was insufficient evidence to verify the claim. Charged with being an accomplice in the robbery, Manolachi spent the next eight months and three weeks remanded in custody in a maximum-security jail in Iaşi, where he shared a cell with almost 50 other men sharing 30 narrow bunk beds. Manolachi was accused of standing guard outside the victim’s home while two other men took her valuables. He had an alibi — he said he was with his girlfriend at the time. Not that he hoped to be believed, such was his faith in the justice system.

Romania outdoes all 27 other EU member states when it comes to violations of the right to a fair trial and other lapses of due judicial process.

“I was already prepared to have to do the time,” Manolachi said in an interview at his home in Iaşi. “This is Romania and you have no chance of getting out of it.” To his delight, the court acquitted him for lack of evidence. (The other two men were convicted. Ghiciuc Bogdan Dumitru got six years and six months while Damian Constantin received five years and four months.) “At the gate, the officer said: ‘Let me check one more time — it’s been years since I’ve seen someone acquitted,’” Manolachi recalled.

But his release soon felt like a cruel joke. Prosecutors appealed and the acquittal was quashed. Facing a five-year prison sentence, he took the fight to Romania’s supreme court, the High Court of Cassation and Justice. He lost. That is when he decided to go into hiding. “You can’t control yourself — you don’t know which way to go, when you know you’ve been acquitted and now you’re convicted,” he said. “Five years, just taken from your life … when you’ve done nothing wrong.” Manolachi escaped capture by moving from address to address, doing odd jobs for cash. While still a fugitive, he filed a complaint to the ECHR. Years passed and he heard nothing back.

Police finally caught up with him in January 2010, shortly after his son was born, tracking him down from information on the birth certificate. Manolachi was sent straight back to jail, though he was not given extra time for his years on the run. He served almost three years in two prisons before being released on parole in August 2012. While in prison, he married his girlfriend. The year after his release, out of the blue, a judgment came from the ECHR ruling that his rights had been violated. The ECHR said Manolachi should not have been convicted after his initial acquittal without new evidence.

It also said the court had failed to hear from Manolachi or witnesses, making its decision solely on the basis of statements given to police and testimony from the previous trial. His case was reopened. In April 2017, the appeal court in Iaşi overturned the conviction and acquitted him. Manolachi is now suing the state for the equivalent of almost a million euros in compensation.

“Errors of judgment“

According to Fair Trials, a criminal watchdog based in Brussels, judicial proceedings can only be considered fair if defendants are guaranteed certain non-negotiable rights. These include access to lawyers and information as well as the presumption of innocence. “It is the state that needs to prove you are guilty, not you who needs to prove you are innocent,” said spokesman Gianluca Cesaro.

“It is the state that needs to prove you are guilty, not you who needs to prove you are innocent.“

Between 2011 and 2018, more than 27,000 people convicted of crimes in Romania asked for new trials on the basis of legal mechanisms known as “revision” and “appeal for annulment”, justice ministry data showed. Courts granted 242 retrials and 17 people were acquitted as a result. Retrials are allowed if new evidence emerges or if the ECHR rules that a defendant’s rights were not respected. Also between 2011 and 2018, 688 people went to court seeking compensation for “repairs of miscarriage of justice”, and 80 were entitled to payouts, the ministry said. No data was available on compensation amounts.

Evidence Omitted

Romania’s most famous case of miscarriage of justice involved Marcel Tundrea, sentenced to 25 years in prison for raping and murdering a 14-year-old girl, in 1992, in the southern village of Pojogeni. Tundrea was 42 when he was convicted. Twelve years later, DNA evidence that was not available at the time of his first trial proved he was not the killer. He was released in 2004. Remus Budai, a prosecutor at the General Prosecutor’s Office, was appointed to work the unsolved case after Tundrea left jail.

“I started with huge prejudice because I didn’t think our justice system could make such a serious mistake,” he said. “There were some things that didn’t seem right.”

During his investigation, Budai uncovered irregularities that he attributed to Ion Diaconescu, the prosecutor in Tundrea’s trial, including the omission of key evidence and a failure to call to the stand Gheorghe Avram, known to police as one of the last people to see the girl alive. According to an indictment filed by the General Prosecutor’s Office, seen by BIRN, Budai concluded that Diaconescu had committed abuse of office, a criminal offence punishable by up to three years in prison at that time. However, no action could be taken against Diaconescu due to a statute of limitations of five years for such offences.

Dan Antonescu, former chief of the homicide department of Bucharest police, said: “We are talking about a prosecutor who intentionally omitted some evidence. He didn’t want to check Tundrea’s alibis, a mistake maintained at least two, even three times.”

In 2010, Budai ordered a DNA test of Avram. It proved he was the murderer.

Tundrea never knew about Avram’s conviction.

He died in 2007 from a lung disease he had contracted while in prison. He was posthumously acquitted.

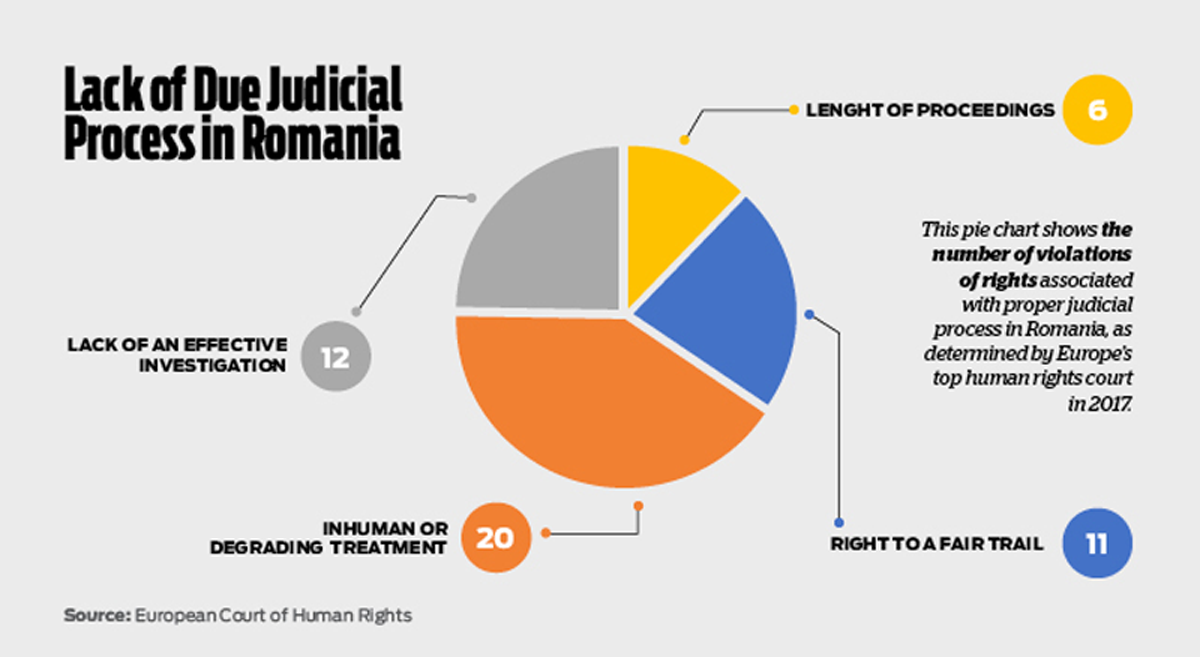

In the same year, ECHR statistics showed that the Strasbourg court upheld 49 complaints of violations of rights associated with proper judicial process in Romania. The ECHR does not judge whether people are innocent or guilty, only whether their rights have been violated.

In addition to 11 violations of the basic right to a fair trial, the complaints upheld by the ECHR included 20 cases of inhuman or degrading treatment, 12 of improper investigations and six of inordinately long proceedings. The court dealt with 3,981 applications from Romania in 2017. Many of the rulings applied to older complaints because it can take several years for the ECHR to come to a decision.

Only three Council of Europe countries had worse records for unfair trials at the ECHR in 2017. Russia had 217 violations of various rights to due process while Ukraine had 78 and Turkey had 62. At the other end of the scale, 10 countries had no violations related to due judicial process at all, according to ECHR rulings: Albania, Andorra, Denmark, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Norway, San Marino and Sweden.

Asked to comment on Romania’s poor record in terms of ECHR decisions, a justice ministry spokeswoman, Ana Mihaila, said the country had the “constitutional and infra-constitutional and legislative framework” necessary for people to exercise their right to a fair trial.

Cristi Danilet, a judge at Cluj Court in western Romania and a former member of the Superior Council of Magistracy, CSM, the body guaranteeing the independence of the judiciary, said the ECHR data painted a misleading picture since many of the Romanian cases were from seven or eight years ago. Since then, he said, CSM reforms had decreased the length of trials and improved the effectiveness of investigations into police brutality and other misconduct. But he said courts were still susceptible to “errors of judgment” caused by false statements gathered by unscrupulous officers.

“I had one case where the cop didn’t find a witness so he asked a ‘service witness’, one of the various police informers,” he said. “The cop wrote the statement, called him, gave him a drink. He didn’t even know what he signed.” He continued: “For errors of judgement, we [judges] are not held accountable. That doesn’t happen in any country in the world.”

After being acquitted for a crime she did not commit, Daniela Tarau set up an association to help victims of judicial errors. Photo: © Robert Kallos

“Gone to hell“

In the summer of 2000, a 29-year-old mother named Daniela Tarau worked for a few weeks as a secretary at a company in Bucharest that recruited workers for jobs in Israel. She made coffee and answered phones before she was forced to leave the firm to have bile duct surgery. The following year, she was summoned to a police station to act as a witness in a fraud case concerning the company. But she soon became a defendant. “I arrived in the morning and I left almost two years later,” said Tarau, now 47. Along with five other staff from the recruitment firm, she was accused of defrauding 44 people who had paid money to get work abroad. Tarau claimed she was no longer working at the company when the payments were made. She was held for 24 hours in a police cell little wider than a bath, with four bunks bolted to the wall.

“I thought I’d gone to hell,” Tarau said. “It was so hot, with a lot of cigarette smoke.”

Then the cycle of pre-trial detention warrants began. First, the prosecutor, Cristian Panait, demanded that Tarau be kept in police custody for five days, then a month. The process repeated 21 times, as if on auto-pilot. Tarau said 28-year-old Panait seemed unstable. He shouted at her and once threatened to throw her out of a window, she said. “From my point of view … the prosecutor was a kind of god who determined whether my place was there or not. And he established that my place was right there … despite the lack of evidence in the file.”

Let Down by Legal Aid

Ineffective representation by some legal aid lawyers in Romania is a major contributor to wrongful convictions, fair trial activists say. “They are extremely poorly prepared,” said Cristi Danilet, a judge at Cluj Court in western Romania. “They don’t make any effort, they’re not interested in the case, they don’t read the file, they don’t talk to the client or they just come to the court and say, ‘We leave it to the discretion of the court.’”

Nicoleta Andreescu, executive director of the Association for the Defence of Human Rights in Romania – the Helsinki Committee, cited a recent example from a court in the capital.

“My colleagues were in court when a lawyer asked for one of his clients to be released because he had a child a home. And the judge asked the lawyer: ‘Sir, do you even know why your client is arrested?’ The client was accused of molesting his daughter.”

In 2017, Romania spent almost eight million euros on legal aid, according to justice ministry figures requested by BIRN.

According to a 2010 study of legal aid spending in various European countries by the Northern Ireland Assembly, Romania spent an average of 23 euros per criminal case, compared with 1,024 euros in the Netherlands and 1,003 euros in Ireland.

Under an agreement between the justice ministry and the National Association of the Romanian Bar, legal aid lawyers working on criminal cases receive between 30 and 112 euros (130 to 520 lei) for each person they represent, depending on the type of work. The average take-home salary in Romania is around 510 euros a month.

Several months later, Panait committed suicide. Some newspapers linked his death to what they described as political pressure to investigate a prosecutor colleague in a separate case. In 2015, Romanian film director Tudor Giurgiu released a movie loosely based on the last months of his life. Whatever the context of Panait’s behaviour, Tarau believes the prosecutor trampled on her rights. When a court finally handed her a suspended prison sentence of three years and three months for fraud, in November 2002, she had been in pre-trial detention in a police cell for 21 months.

“What is worrying from our point of view is that the length of time a person can be in pre-trial detention is excessive,” said Nicoleta Andreescu, executive director of the Association for the Defence of Human Rights in Romania – the Helsinki Committee, a non-governmental organisation based in Bucharest.

“This pre-trial detention is often a formality because the prosecutor asks for 30 days and the judge allows it, and basically they renew this automatically. Legally, you can’t be in pre-trial detention without being in court for more than 180 days.”

The five others accused of defrauding the customers —including a cleaning lady at the firm and her husband, a driver — were also convicted.

After her release, Tarau sent dozens of complaints to parliament, the president’s office and the courts maintaining her innocence and asking for her case to be reviewed. She came up with a way to see if anybody was reading them: stapling pages in the middle. “I went to the court’s archive … and I found them still stapled,” she said.

Tarau filed a complaint with the ECHR, which ruled in 2009 that her right to a fair trial had been violated. It said she had been denied adequate legal aid and prevented from cross-examining victims of the crime or calling witnesses. It agreed that her time in pre-trial detention was excessive. Six years later, a court in Bucharest retried her case and she was acquitted. She went on to seek 900,000 euros in compensation and was eventually awarded 100,000 euros.

“Just satisfaction“

Tarau also received 4,000 euros in “just satisfaction”, a form of compensation awarded by the ECHR but paid by the country concerned. It is typically much smaller than damages given by domestic courts. According to the Council of Europe, the human rights body that monitors just satisfaction payments, Romania has shelled out 53.7 million euros in such compensation over the past 10 years.

In 2017, Romania paid 2.6 million euros in just satisfaction following ECHR decisions. By contrast, Denmark and Norway paid nothing and Sweden paid 5,000 euros last year. At the other end of the scale, Russia and Turkey paid 15 million euros and 12 million euros, respectively.

In Romania, all damages are paid by the finance ministry. Judge Danilet said that in theory, the ministry can sue judges or prosecutors responsible for miscarriages of justice to reclaim money, but in practice this never happens. “A miscarriage of justice is a decision taken by a prosecutor or a judge conspicuously against the law or the evidence in the file, whether done intentionally … or through serious incompetence,” he said.

Heavy Caseloads

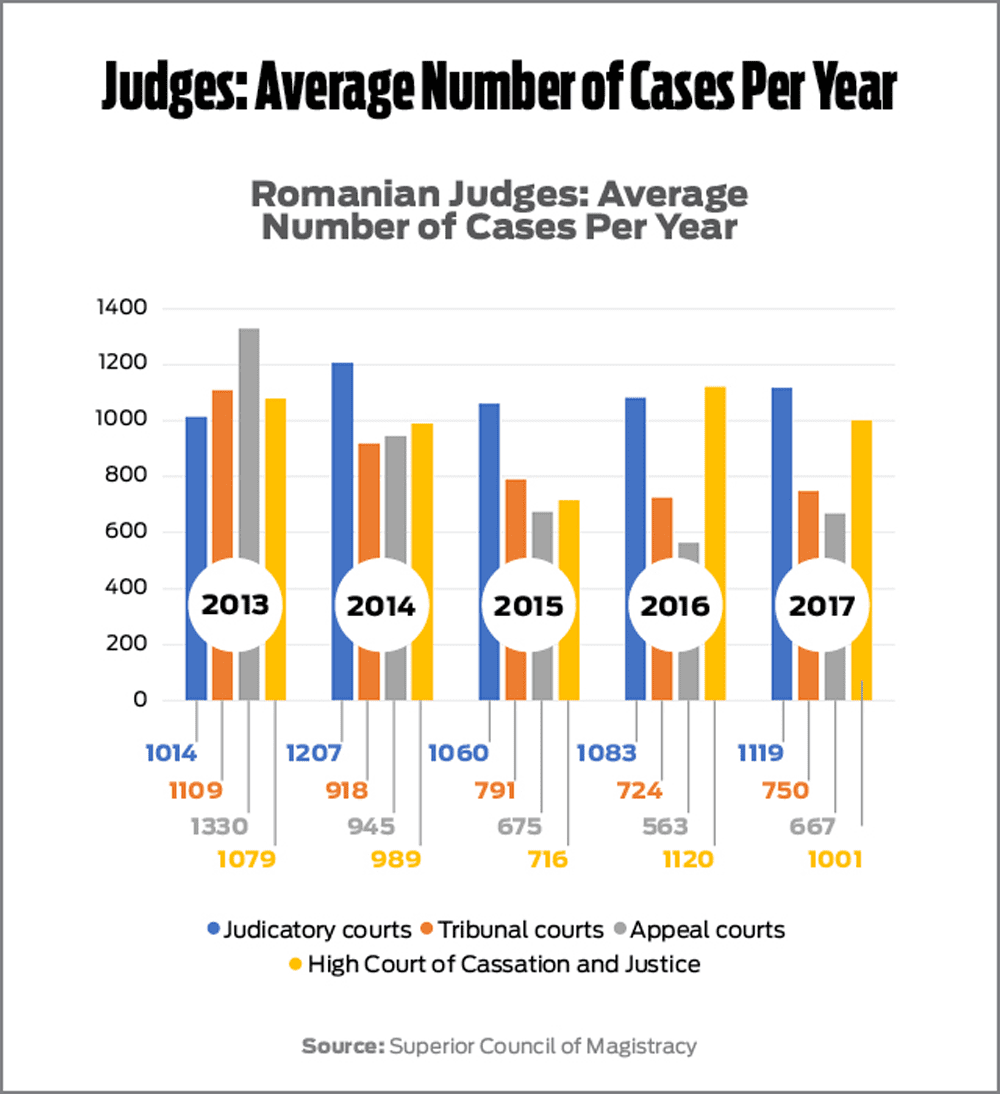

Judges in Romania are legally required to allocate fixed amounts of time each week to specific tasks: two days for reading files, two days for writing decisions and one day for public hearings. In practice, many are overloaded by caseloads and forced to skimp on specific details, say fair trial advocates.

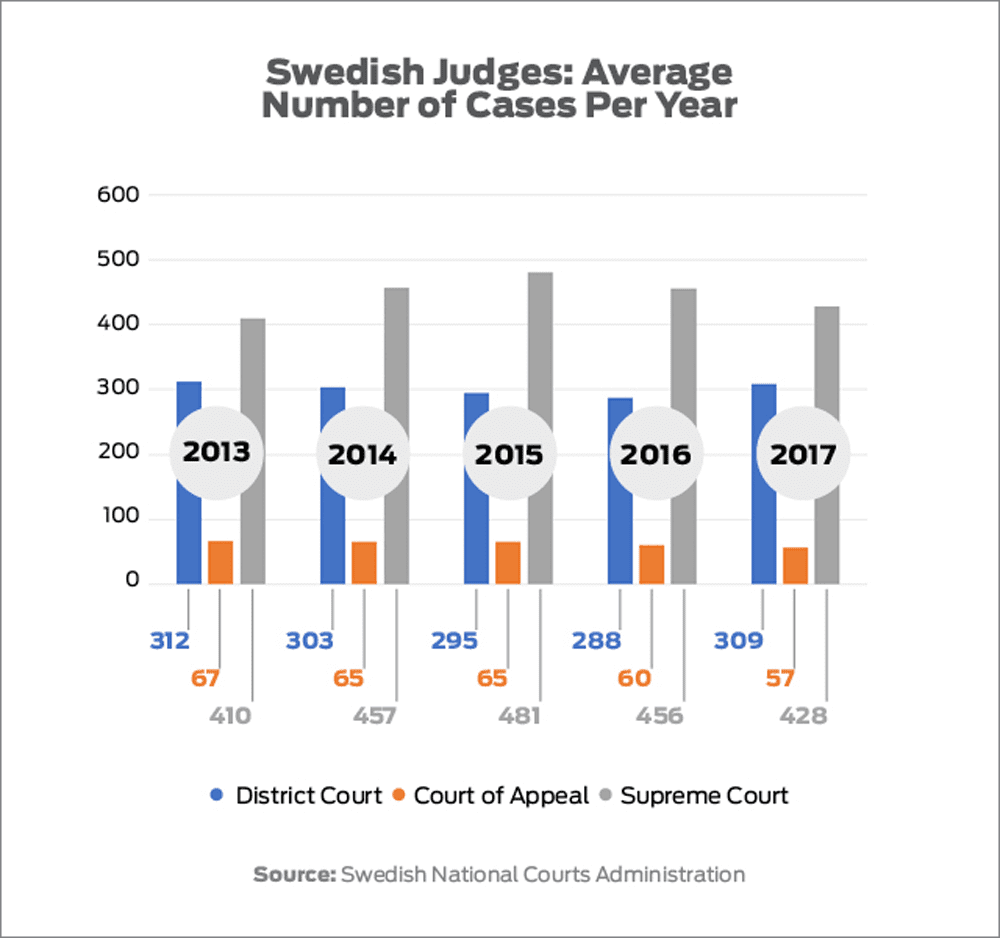

According to data from the Superior Council of Magistracy, which oversees the justice system, judges at the High Court of Cassation and Justice on average deal with around 1,000 cases a year.

By comparison, their counterparts at the Supreme Court in Sweden deal with fewer than 500 cases per year, according to the Swedish National Courts Administration.

Judges and prosecutors can be held accountable through disciplinary action or criminal proceedings, Danilet added. Disciplinary sanctions range from warnings and docked salary to suspension and exclusion from the bench. The penalty for criminal offences is jail time. The CSM reported that in 2017 it dished out 22 disciplinary sanctions for judges and 10 for prosecutors. It did not clarify which punishments were related to miscarriages of justice or other wrongdoing.

Lawmakers have cited cases such as Manolachi’s and Tarau’s as justification for the justice system reforms they started ramming through parliament in 2016. Critics call the reforms a blatantly political response to a string of corruption cases that have claimed senior scalps — including PSD leader Liviu Dragnea, who in June got a three-and-a-half-year prison sentence for abuse of office, pending appeal.

International voices including the European Commission and the US State Department have joined the chorus of condemnation. “They [the reforms] contain a number of measures weakening the legal guarantees for judicial independence which are likely to undermine the effective independence of judges and prosecutors, and hence public confidence in the judiciary,” the European Commission said in a report in mid-November. Among areas of concern, it singled out the new special prosecution unit for investigating offences committed by judges and prosecutors and “extended grounds for revoking members of the Superior Council of Magistracy”.

In September, some 300 judges held a silent protest outside the Bucharest Court of Appeal, holding signs saying “For independent justice”. Back in Iasi, Petrica Manolachi does whatever building work he can get his hands on as he fights for compensation. In his free time, he tinkers with his car and attends meetings of a Rover automobile club. The ECHR awarded him 3,000 euros in just compensation but he is seeking additional damages through Romanian courts. In March, the Suceava Tribunal court decided against him, ruling that there was nothing illegal about his arrest or time in pre-trial detention, even though he was later acquitted. His appeal is ongoing at the Suceava Court of Appeal.

In Bucharest, Daniela Tarau has set up an association to help victims of judicial abuse know their rights and seek redress. She married a policeman, got a law degree and completed a Masters at the Police Academy. She went on to do a PhD on conditions in Romanian prisons and wants to write a book on the subject. Recalling her ordeal, she concludes that her case was simply minor enough to slip through the cracks of a broken system — with devastating consequences for her personally. “It wasn’t an important file,” she said. “It was one of those files that just proceed automatically… ‘Who’s this? A nobody.’”

Sweden Makes Amends for Miscarried Justice

Five thousand kilometres from Romania on El Hierro, the smallest of Spain’s Canary Islands, Kaj Linna was reliving how he spent 13 years in a Swedish jail, wrongly accused of murder. “I was in isolation for many months, years,” said the 56-year-old Swede. “You can make me mad, you can make me sad, you can make me cry, but you can’t break me.”

Kaj Linna stands by the wall of a house he is rebuilding on El Hierro in Spain’s Canary Islands, where he is building a hotel with money from Sweden’s highest compensation payout for a miscarriage of justice. Photo: © Lorelei Mihala

Standing by a half-built stone wall on a hill overlooking the ocean, Linna explained how he is building a hotel with money from the biggest compensation payout for a miscarriage of justice in Sweden’s history: 1.8 million euros (18 million Swedish krona). Sweden’s Chancellor of Justice told BIRN the payout was a “friendly settlement” to compensate Linna for his time behind bars after he was exonerated in 2017.

His conviction was quashed and he was released from serving a life sentence after Anton Berg, a producer at a public radio station in Stockholm, started investigating his case. “I found out that there was really no hard evidence, there were no DNA traces or footprints,” said Berg via Skype. “Actually, nobody even saw Mr Linna at the murder scene.” Berg caught a witness on tape admitting that he had falsely implicated Linna in a robbery-turned-murder in the remote northern Swedish village of Kalamark. It was enough to trigger a retrial at the Supreme Court. “I knew all the time that I would be free, but I never knew it would take 13 years,” Linna said. While in prison, Linna had filed an application with the European Court of Human Rights but the court ruled that his complaint was inadmissible.

Last year, Linna married Petra Wullrich, his Spanish teacher in prison. The two had fallen love while he was a prisoner. When things got serious, she resigned and continued to visit him as his fiance. After his release, they moved together to El Hierro to start a new life.

Linna said he hoped Sweden would one day create a statutory body like Britain’s Criminal Cases Review Commission, which is responsible for investigating alleged miscarriages of justice. No such body exists in Romania either.

First published on 18 December 2018 on Balkaninsight.com.

This text is protected by copyright: © Lorelei Mihala, edited by Timothy Large. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Daniela Tarau languished in a police cell for 21 months awaiting trial for a crime she did not commit. Photo: © Robert Kallos

This article was produced as part of the Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation and Open Society Foundations in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.