One day in May 1993 artist Lucia Lienhard-Giesinger from Austria’s state of Vorarlberg put coloured sketches made with wax crayons into an envelope and got into her car. News reports on the Balkan war, and the number of truckloads of relief goods collected through Austria’s relief scheme Nachbar in Not (Neighbour in Need), were prominent on prime time TV at the time.

Only twenty kilometres separate her home in Altach from Frastanz, where a central refugee home had been set up in the old barracks of Galina. Lucia turned the ignition key and the car started moving slowly. She reached over to the passenger seat, where she had put the wax crayon sketches, to make sure her idea was still there. These templates were to be used to make quilts. Lucia intended to encourage the refugee women to produce patchwork quilts together, to put something into their hands, to give them something to do.

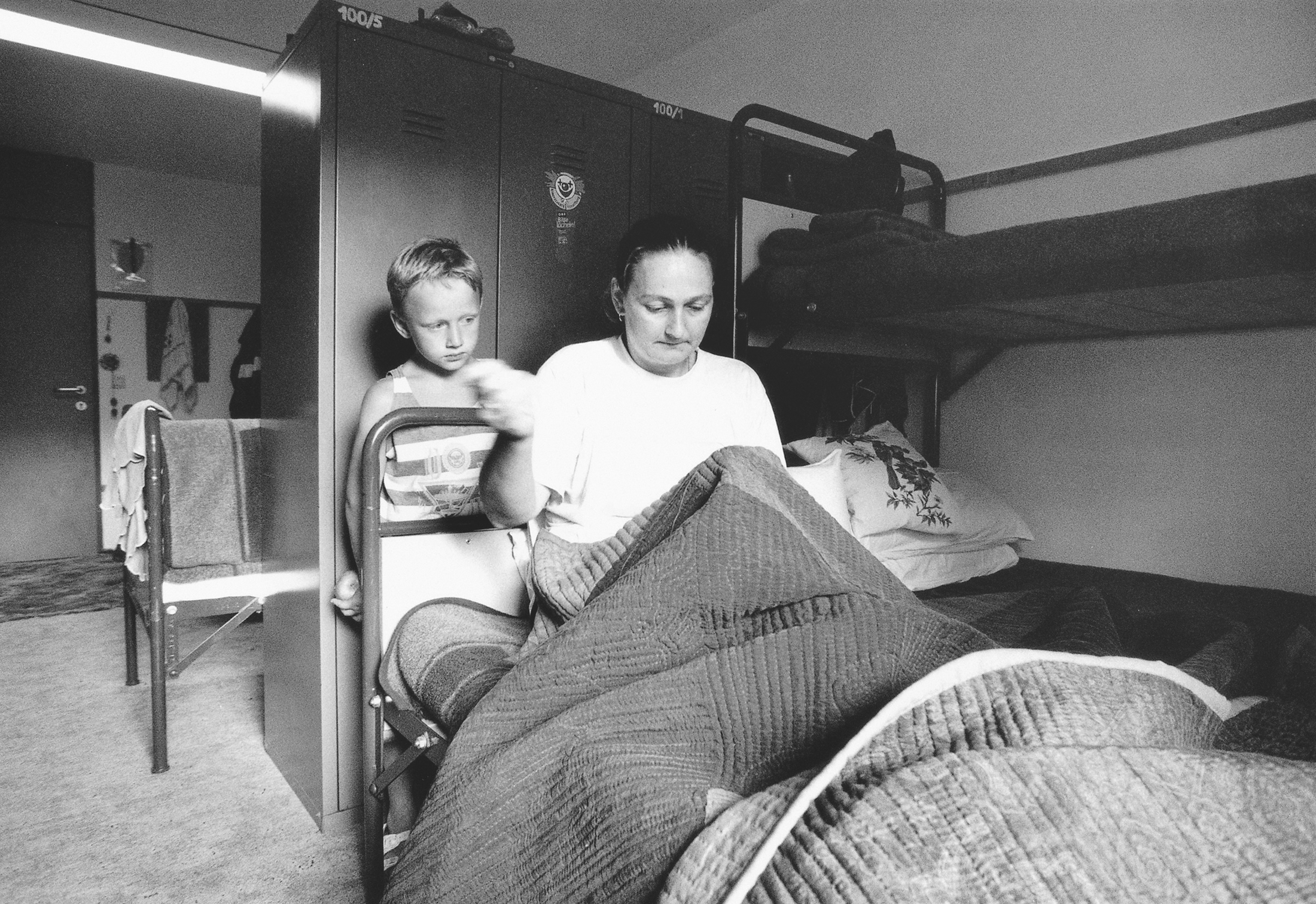

Everything started with an idea in the refugee home Galina in Frastranz during the early 1990s. Photo: © Nikolaus Walter

What she didn’t know at that point was that the unique items, the many layers of fabric, joined together by seams centimetre by centimetre, would enable these women to return to their homes at a later point in time, and to have a life afterwards.

Bosna Quilts

The workshop was created in 1993 during the Bosnian war in the refugee home Galina in Vorarlberg. The textile unique pieces are designed by Lucia Lienhard-Giesinger in Bregenz and sewed by eleven women in Goražde and Sarajevo by hand. After more than 20 years, the Bosna Quilt workshop in Bregenz has settled down. If you want to see Bosna Quilt, there is now a place where you can do that. But they will continue to be shown in exhibitions.

The drive from Altach to Frastanz takes less than half an hour. The journey that Lucia embarked on in Mai 1993, however, has still not ended.

One day in autumn, more than 24 years later, Lucia is standing in the showroom of Bosna Quilts in Bregenz making coffee. Her blue eyes gaze out from below her bob, now turned white. Quilts decorate the walls, a vase with a bouquet of flowers stands on a little table, creating the clean and tidy atmosphere favoured by someone to whom aesthetics matter.

The workshop sells 80 quilts a year – to Vienna and Zurich, to Gothenburg and Novosibirsk, to museums, churches, private homes. Each artwork costs about 1,000 euros. Demand is stable.

The refugee women from Galina in Frastanz have become employees down in Bosnia. The Bosna Quilts business, which started in the barracks’ garage, to this day provides a reliable income to eleven women on the banks of the Drina river in the city of Goražde in east Bosnia, some 50 kilometres from Sarajevo.

Back then, during her first drive to Galina, Lucia was nervous. Along the road, Vorarlberg’s municipalities, Röthis, Rankweil and half of the Rhine Valley, lined with prosperous family homes, passed by the window: a never-ending chain of economically successful biographies – each with their own house, dog and garden. The women at Galina had lost everything. The people at the refugee home had to pass the days somehow. The government in Vienna had created a special status for the refugees from the Balkans as “de facto” refugees who were offered temporary protection until they could be expected to return to their homes. They did not have to go through individual asylum procedures; neither did they have access to the labour market. The quilt workshop, initially a makeshift business that opened in a garage, soon filled with 30 women. The needles flashed in and out. Lucia’s initial fear that the women would reject her ideas was drowned by the stitch movements. To the women, quilting offered variety, some money, a little bit of gossip. The monotony of the sewing process, the quilt lines that slowly take shape, also helped. “Sometimes it is necessary to repress your memory,” says Lucia.

“Quilting has saved my life,” says Safira Hošo, who fled from Goražde to Austria in 1993. First, it supported her in the Galina garage in foreign Vorarlberg; later in her home country that Hošo had to return to in 1997, a country that has become foreign too. At that point Goražde had lost two thirds of its population; unknown faces occupied the destroyed houses. There was no work. “The quilts were my only chance,” says Safira Hošo today.

After returning to her home, she rounded up ten women in Goražde to produce quilts. Sada, who looks out of her kitchen window onto the Serbian Orthodox cemetery, where the dead of the others lie; Vesna, whom Safira knows from Galina; Emina, who draws the waves of the Drina river on her quilts; and the others, whose life paths have been divided into a before and after by the war. Lucia sends them her designs from Vorarlberg. Stitching together the layers of the quilt, each woman sews in her individual style. For each quilt, they divide up the work between them – they did so back at the refugee home on the main road, and they still do today in Bregenz and on the banks of the Drina river.

It has been that way for more than 24 years.

Lucia Lienhard-Giesinger in the design studio and showroom of the Bosna Quilt workshop in Bregenz. Photo: © Daniel Lienhard

“If you don’t carry on, I’ll go crazy,” Safira had threatened Lucia before returning to Goražde. She took the fax machine with her: so that they would stay in touch, so they would continue to quilt. Today the women earn a regular income with their manual work, in a city where unemployment is still very high. Almost every month Lucia sends her designs from Vorarlberg while a minivan drives the finished quilts from Bosnia back to Bregenz, along the Rhine Valley, passing the former Galina refugee home, which was closed in 2011.

“My soul is satisfied,” says Safira Hošo today. Lucia Lienhard-Giesinger smiles. “As long as it is reasonable, and we are healthy, we will continue to work together,” she says, laying new designs on the floor.

A modified version of this text was published on 15 July 2015 in Die Presse and on 18 August 2015 in the Vorarlberger Nachrichten.

This text is protected by copyright: © Eva Konzett. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture and picture in the info box: © Daniel Lienhard.