Low birth rates, rampant emigration and an ageing population all take their toll on a country facing critical labour shortages.

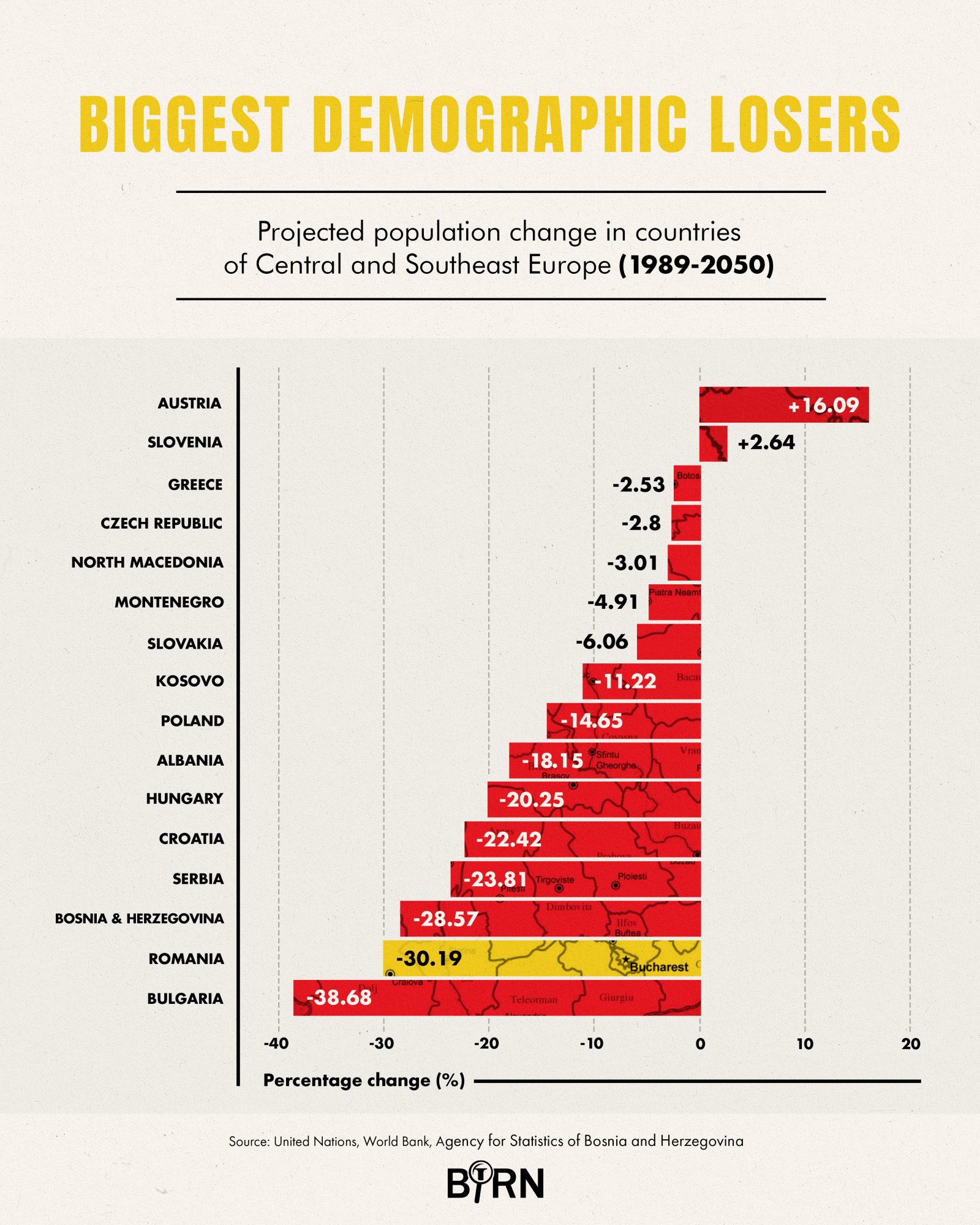

Percentage-wise, other former communist Eastern European countries have lost more population than Romania in the past three decades. What sets Romania apart is the sheer scale of the loss.

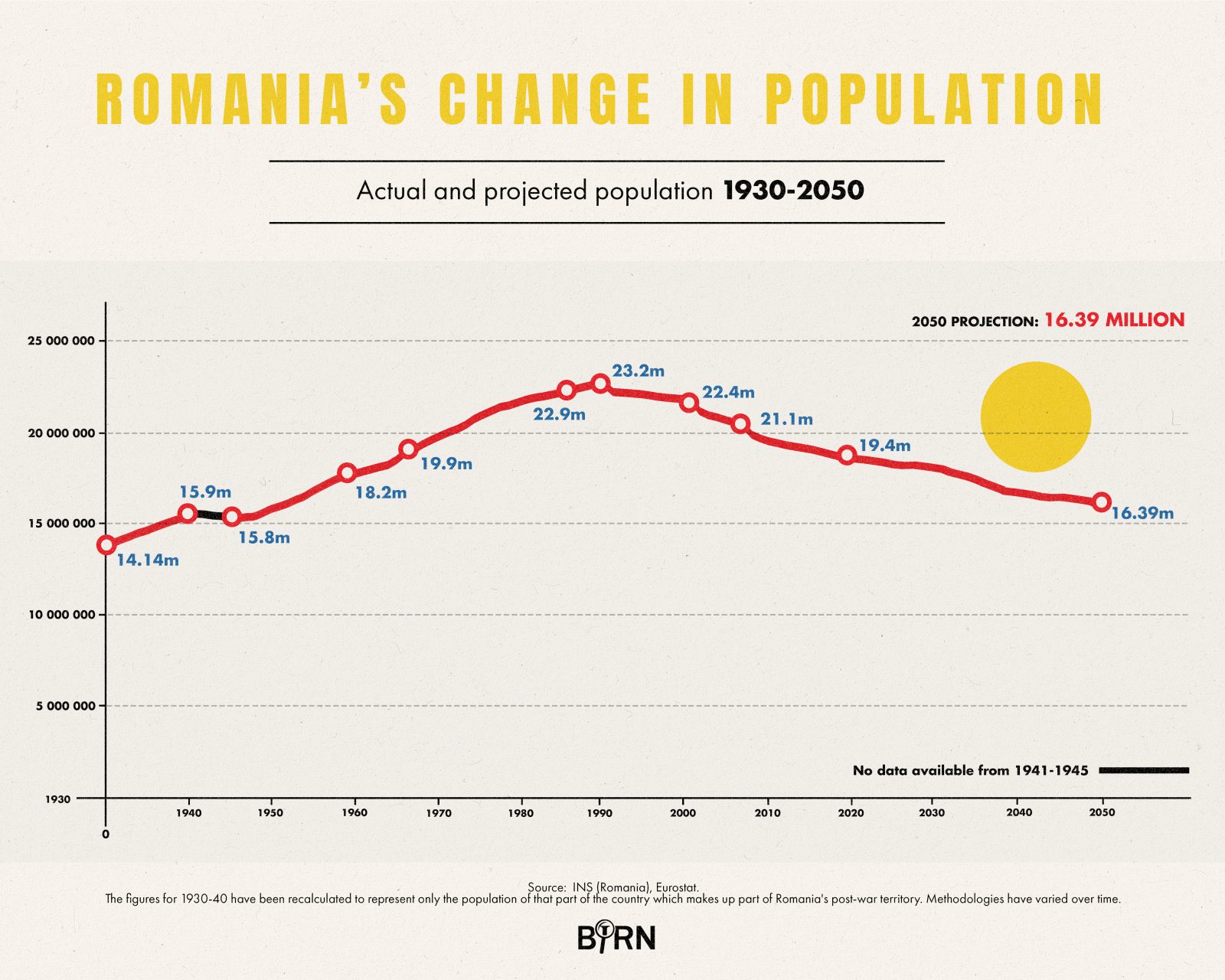

In 1990, the country’s population peaked at 23.2 million but at the beginning of 2019 it was 19.4 million. So, since the fall of dictator Nicolae Ceausescu in 1989, the country’s resident population has declined by 16.4 per cent or 3.8 million people. That is more than the entire population of several of the other former communist states. Of course, the reason that the number is so high is because Romania is the second-largest of the former non-Soviet countries in Eastern Europe.

It is a national trauma nonetheless, leading to critical labour shortages and a lack of key personnel such as medical staff. It results in the depopulation of rural areas and many small towns, or just leaves them with elderly people. As elsewhere in the region, Romania has been affected by low birth rates, emigration, an ageing population and very little immigration or migrant return to stem the decline.

And the projections do not look good: according to the Romanian National Institute of Statistics, by 2050 the country’s population could shrink to 15 million or 35 per cent less than in 1990. (A UN projection is less gloomy, foreseeing population at 16.39 million in 2050, a fall of just over 30 per cent.)

Romania’s change in population. Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

If Romania’s shrinking population is a problem today, it is one that Ceausescu anticipated and feared. In 1967, in his bid to make Romania 30 million strong, he as good as banned abortion and contraceptives, leading to more than two decades of domestic and national misery including back street abortions and huge numbers of children abandoned in grim orphanages.

The overall Ceausescu legacy is a major reason why the country emerged from communism in such dire straits and why it has taken so long to recover.

Biggest demographic losers. Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

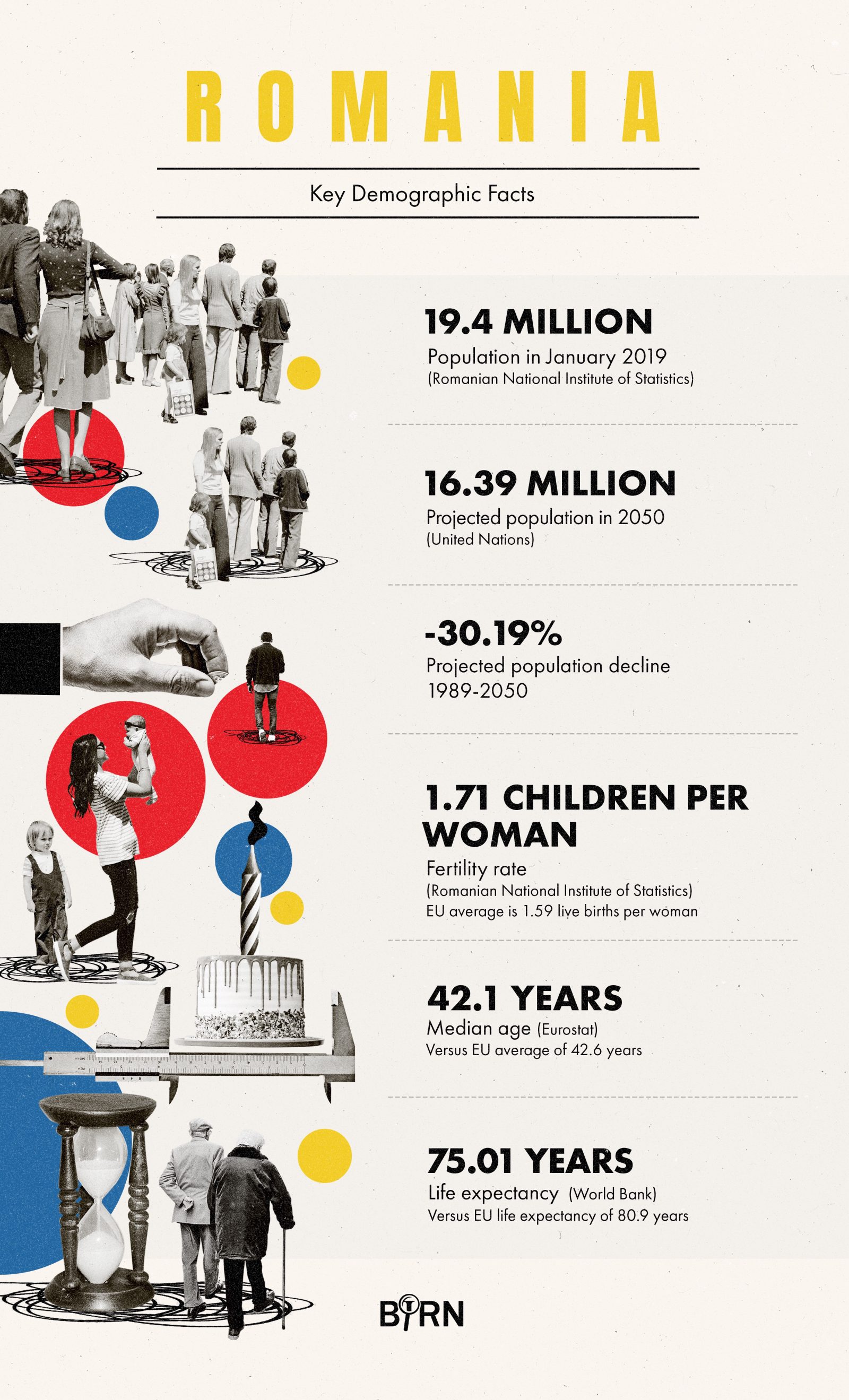

While Romanian women had an average of 2.2 children in 1989, the country’s fertility rate declined to a low of 1.27 in 2001 but it has been gradually climbing back up since then to 1.71 in 2017. With so many young people out of the country though, that is not enough to halt the natural decline.

In 2018, Romania recorded 75,729 more deaths than births and the country continued to age. Today the median age is 42.1, slightly below the EU median age of 42.6. The difference with Western European countries, of course, is that they have significant immigration to make up for natural demographic shortfalls.

Romania key demographic facts. Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

Apart from its low birth rate, emigration is the other main reason for Romania’s shrinking population. Over the past few decades, this has evolved over several distinct phases. During the Ceausescu era, few Romanians could leave the country, with two distinct exceptions: Jews and ethnic Germans. Large numbers of them were in effect ransomed by Israel and West Germany which, under various guises, bought exit visas for them. By 1990, there were relatively few Jews left and some 200,000 of the remaining ethnic Germans then left rapidly for Germany.

The second phase lasted from 1990 to 2002. In this period, the economy collapsed and around half of jobs were lost. It was hard for Romanians to get visas to Western countries, though large numbers did manage to get to those countries, even if they were then forced to work illegally. At the beginning of 2002, the next phase began when visas were abolished for the EU’s border-free Schengen zone. This opened the gates.

Remus Gabriel Anghel, the head of the Centre for Comparative Migration Studies at Babes-Bolyai University in Cluj, believes that from then until 2007-08, some one million to 1.2 million left for Italy while another million went to Spain. The situation was so dramatic, he says, that virtually whole towns in the hardest-affected regions emptied. This period came to an end because of the economic crisis that hit Italy and Spain hard and because Romania joined the EU at the beginning of 2007. Since then, says Anghel, approximately one million have left.

Initially nine of the then 26 EU countries imposed transitional labour restrictions but these have since been lifted. Britain lifted restrictions in 2014, for example, leading to a huge leap in the country’s Romanian population, which hit 415,000 in 2018 compared with 19,000 in 2007.

One ongoing issue is that of families where one or both parents are abroad and which can have deep and negative effects on the children left behind.

It is hard to work out precise figures for the numbers abroad, however. The age of cheap travel means that there is a lot of circular migration — for example men going for three months to work in a slaughterhouse in Germany, returning home for a few months and then leaving again, or women going to care for the elderly in Italy for similar short term contracts. One ongoing issue is that of families where one or both parents are abroad and which can have deep and negative effects on the children left behind.

In 2016, there were 95,308 children with parents working abroad, some 34 per cent of them with both parents abroad. Today the situation is changing again. In 2008, people sent back remittances of 6.4 billion euros, representing 4.5 per cent of gross domestic product, but by 2016 that had dropped to 3.2 billion euros or 1.9 per cent of GDP.

EUROPE’S FUTURES

Europe is living through its most dramatic and challenging period since World War II. The European project is at stake and its liberal democracy is being challenged from both inside and outside. There is an urgent need from all quarters of state and non-state actors to address the burning problems, both to buttress what has been painstakingly achieved through the political peace project.

From 2018 to 2021, each year six to eight leading European experts are taking up engagement as Europe’s Futures fellows. They create a platform of voices presenting ideas for action whose goal is to reinforce and project forward a vision and reality of Europe. Europe’s Futures is an endeavour based on in-depth research, concrete policy proposals, and encounters with state and civil society actors, public opinion and media.

In other words, for the country as a whole, while emigration initially helped resolve the problem of unemployment and played a significant role in reducing poverty for those left behind, as Romania has become richer, the problems of skills and labour shortages have emerged and remittances are less important to the country as a whole.

According to the World Bank, 20.6 per cent of the country’s working age population was abroad in 2017. While emigration continues it has stabilised but, at the same time, there is increasing migration within Romania. In 2007, some two-thirds of business and Romania’s GDP was focused on Bucharest but now that has dropped to 44 per cent, according the Anghel.

“In the meantime, cities like Timisoara, Brasov, Sibiu and Cluj got a lot of investment and began to develop more than before and so what we see is that these cities started to attract population from the east of the country and even from within (richer) Transylvania itself.”

Today, says Anghel, there is a small amount of return migration and immigration, mostly from Moldova, though large numbers of Moldovans only acquire easy-to-get Romanian citizenship so they can work and live elsewhere in the EU. The government, however, has begun to open the door to workers from elsewhere, such as Vietnam, because of increasing labour shortages and wages are increasing.

Another result of labour shortages is that Roma, previously discriminated against, are finding employment in sectors where it would have been hard for them to get jobs before. While Romanian governments, just like others in the region, need to plan for a future with fewer but ever older people and find ways of attracting migrants back home, Anghel notes that migration has become “the main process of social change”.

In the past, people left and remittances came back. “People just tried to make ends meet.” Now he says things have changed. “Romania is no longer a poor country in the way that it was and now people don’t need just money. They have had experience of the West,” he said, adding that they want good schools, hospitals and services. They have higher expectations than before and “this is something the government does not really understand”.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN or ERSTE Foundation.

First published on 28 November 2019 on Reportingdemocracy.org a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The article was produced within the framework of the Europe’s Futures project.

This text is protected by copyright: © Tim Judah. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures and graphics are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy