Slovenia is one of the few former communist countries in Europe whose population is increasing — so why aren’t demographers popping champagne corks?

From the Adriatic to the Black Sea, the story of the demographic death spiral is the same: people are ageing in countries that need more coffins than cots. People are emigrating, no one is immigrating and the result is falling populations. And then there is Slovenia.

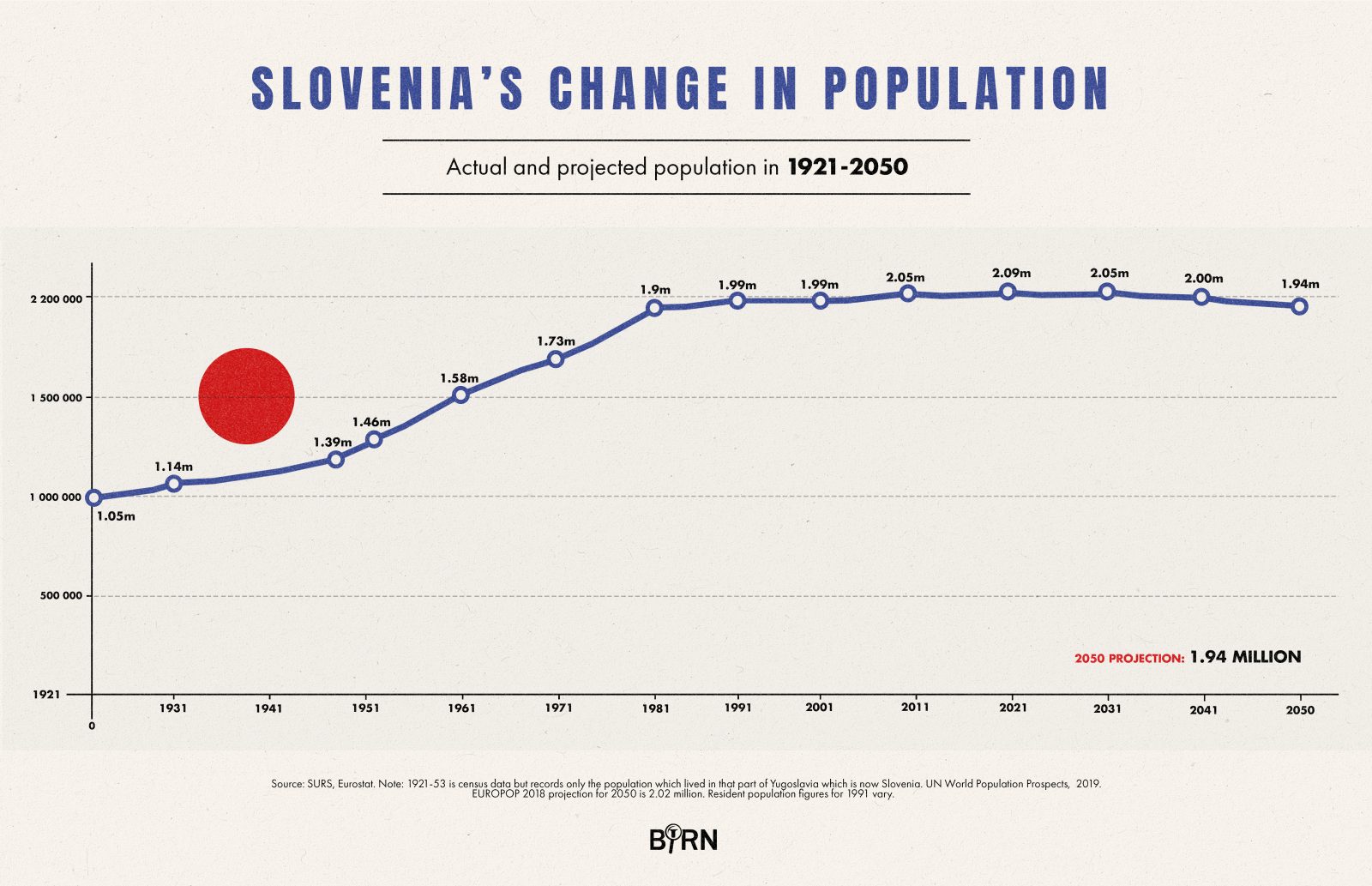

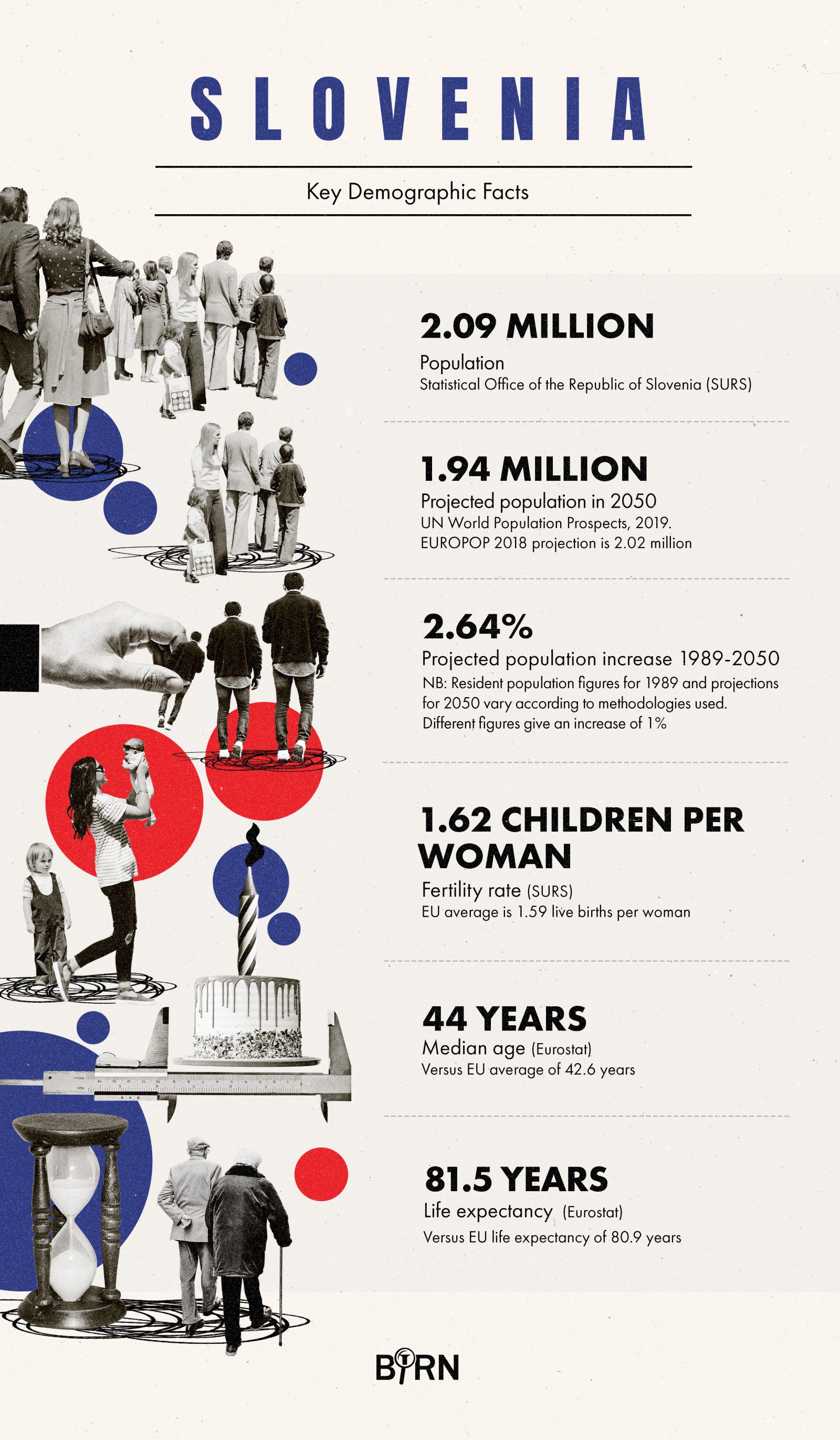

At the beginning of 2020, according to Slovenia’s Statistical Office, its population was 2,096,000, an increase of almost 15,000 on the year before. At independence in 1991, Slovenia’s population was some two million, so by 2020 its population was almost five per cent higher. These figures make Slovenia an outlier. It is one of only a few of the former communist countries in Europe whose population is increasing and which has more people today than it had three decades ago.

EUROPE’S FUTURES

Europe is living through its most dramatic and challenging period since World War II. The European project is at stake and its liberal democracy is being challenged from both inside and outside. There is an urgent need from all quarters of state and non-state actors to address the burning problems, both to buttress what has been painstakingly achieved through the political peace project.

From 2018 to 2021, each year six to eight leading European experts are taking up engagement as Europe’s Futures fellows. They create a platform of voices presenting ideas for action whose goal is to reinforce and project forward a vision and reality of Europe. Europe’s Futures is an endeavour based on in-depth research, concrete policy proposals, and encounters with state and civil society actors, public opinion and media.

With looming future pension and social care commitments, planners in every European country want their populations to grow, but in Slovenia they are far from popping the champagne corks.

Slovenia’s headline news of increasing population masks serious underlying demographic problems.

Like all other Europeans, Slovenes are ageing. Life expectancy is 81.5 years, which is a little higher than the EU average. It is also the highest of any former communist country in Europe. Life expectancy in neighbouring Croatia, for example, lags far behind at 78.2 years. More Slovenes die than are born — precisely 900 more in 2018 — and although the fertility rate of Slovene women has increased to 1.62 in recent years, higher than the EU average of 1.55, that is way below the 2.1 figure needed for a population to replace itself.

However, Slovenia’s increasing fertility rate does not mean that more babies are being born. It simply means that the rate is going up because the number of women of reproductive age against which it is calculated is going down.

The main reason Slovenia’s population is increasing, then, is that, at least until coronavirus hit, labour shortages meant the country was importing as many workers from abroad as it could get.

At the same time, in 2019 the number of resident Slovene citizens fell by some 3,200 while the number of foreigners increased by nearly 18,200, meaning that 7.5 per cent of people in Slovenia are foreigners. Of those, 86.4 per cent come from the rest of former Yugoslavia, of which 54 per cent are Bosnians. In 2018, the last year for which this data is available, 28,455 immigrated to Slovenia, including some 4,300 citizens returning home, while 13,527 left the country, just under half of whom were Slovenes. This means that 14,928 more immigrated than emigrated. Without this net immigration, the country’s population would be falling.

If you look at Slovenia’s population for the past three decades, the total fluctuates in an unusual way in the 1990s, but this oddity had as much to do with changes in the way people were counted as anything else. For example, thousands of former Yugoslavs who had not taken citizenship or registered as foreigners at independence were “erased” from the population total, only later to be restored.

Slovenia’s change in population. Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

In fact, the country’s population has remained remarkably stable around the two million mark but has increased in recent years thanks to immigration. In most other countries it is difficult to know how many have emigrated. Slovenia, however, has much better data than most because it counts its people via a population register and obliges everyone to register their residence and to deregister if they go abroad.

While this still leaves room for a margin of error, including a grey zone for foreign workers such as Bosnians registered as resident but actually “posted” to Germany or elsewhere in the EU, Danilo Dolenc, the head of Demography Statistics at Slovenia’s Statistical Office, said: “We know that over-registration is a fact and therefore we have an overestimation of the population, but it is less than one per cent.”

Slovenia. Key demographic facts. Infographic: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

The critical issue, according to Alenka Kajzer of the Institute of Macroeconomic Analysis and Development (IMAD), is that while the total population number has been more or less stable, its structure has not been. The number of people who are aged 65 and above “is increasing sharply”. In 1990, this segment of the population represented 10.6 per cent of the total but since then it has almost doubled to almost 19 per cent, and Kajzer said it is projected to swell to about a quarter by 2030. At the same time, the working age population (between 20 and 64) has been shrinking, especially since 2012.

‘They Just Want a Better Life’

At 22,080 euros, Slovenia has the highest gross domestic product per capita of all former communist countries in the EU. The country is well run and its quality of life is high. And yet many young Slovenes still want to emigrate, with the largest numbers going to work in Germany and Austria where GDP per capita is roughly double.

Mirjam Milharčič Hladnik of the Slovenian Migration Institute said that while people leave for a higher standard of living, another reason is often to escape from stifling family control.

Slovenia, she said, is a country where “villages are small, towns are small” and ambitious young people do not want to be sedentary, living the stereotype of being the hundredth generation in their village. Today’s young people want to see the world, “today, as in the past”, she said. Milharčič Hladnik, co-author of a new book on the history of Slovene migration, said emigration is deeply rooted in Slovene tradition. In the century to World War II, some 440,000 emigrated from what she calls “Slovene territories”, a term that encompasses today’s Slovenia plus some neighbouring regions — for example, around the Italian port of Trieste.

It is a rough figure too because this estimate does not include those who returned and it includes Italians, Germans and others who lived here. However, she said, it is an indication that, at one time, this region had “one of the highest rates of emigration in history”.

Before World War II, people left because they were poor, in debt, because of inheritance laws and for many other reasons. Today Bosnians come to work in Slovenia but after the Habsburg seizure of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1878, Slovenes went to work there as miners and foresters. Before World War I, booming Trieste and Vienna were big magnets and further afield Slovenes emigrated especially to the United States and Argentina. When the US slammed the door to mass immigration in 1924, they went to Germany, Belgium and France. For almost a century until 1956, a Slovene community from the Goriška region blossomed in Egypt, especially in Alexandria. The majority who left to work there were women. They came to be known as Aleksandrinke, and often went as nannies for European families. In the wake of World War II, some 25,000 fled Josip Broz Tito’s advancing communist army, and another 45,000 crossed the border illegally between 1945 and 1962. At the same time, Italians fled Istria and what is now the Slovene coast, which were Italian between the wars.

Some Slovenes also came to Slovenia from Italy. They helped repopulate once Italian-inhabited towns like Koper (Capodistria), as did Slovenes encouraged to move to the coast from the interior.

In communist Yugoslavia, Slovenia began to grow wealthy but still many Slovenes fanned out to work in the other republics. From the mid-1960s, Slovenes, like other Yugoslavs, went to work as gastarbeiters in Germany and other countries but, from the 1970s, Yugoslavs from the poorer republics also came to work in Slovenia’s new industrial towns.

Today, the nature of migration to and from Slovenia may have changed, but Milharčič Hladnik said people leave for the same reasons. “They just want a better life.”

All of Europe is ageing so in this respect Slovenia is not an outlier. Today its share of people aged 65 and over is less than the EU average but Kajzer said that is set to change.

In one or two decades, the country will have an elderly share much higher than the EU average, meaning that it will be faced with one of Europe’s “biggest increases in age-related expenditures” such as pensions and social care. And this, she said, “is not just due to demographic changes, but to the fact that our social security system is not adapted to the new demographic situation”.

In 2016, an IMAD report noted that, on current projections, age-related public expenditure would reach a third of gross domestic product by 2060, which would be among the highest in the EU. It also said the pension system was “already unsustainable” and that the country had “no comprehensive system for long-term care”.

In 2017, IMAD participated in drawing up a strategy to cope with Slovenia’s ageing population. It noted that expenditure on pensions was set to “increase at the fastest rate among all EU countries” and that given their relatively low level, the poverty rate amongst pensioners threatened “to become more acute”. “Unfortunately,” said Kajzer, no changes have yet been enacted to tackle the coming crisis and “broad action plans” are “still in preparation”.

According to Damir Josipović of the Institute of Ethnic Studies, Slovenia’s looming demographic problems are made worse by the fact that successive governments have attempted to deal with them with two major schemes incorporating elements of social engineering.

One is that, as a result of trying to get more young people into work, some 300,000 people who are younger than 65, many in their 50s, are already retired. He said this means Slovenia’s pension system is already creaking under a “huge burden”.

The second problem, he said, is that in the wake of independence, governments sponsored a huge expansion in higher education. Today the consequences of this are that while Slovenes are well educated there are not enough of them able or prepared to work in, say, construction or manufacturing.

There are also too many well educated graduates for not enough jobs requiring their skills, so some accept work below their qualifications, meaning a loss of human capital. However, while the number of working-age Slovenes is contracting naturally, the comparative shortage of jobs for those with higher education is also a major factor behind their seeking jobs abroad.

At the same time, some of those jobs are being filled by immigrants; being in the same predicament at home, they are taking them even though they may be below their status too.

This, said Mirjam Milharčič Hladnik of the Slovene Migration Institute, has led to the evolution of stereotypes — that it is well educated Slovenes emigrating and poorly educated Bosnians, Macedonians and others “coming to Slovenia to build roads”.

In fact, the data of the last few years shows that the educational background of immigrants and Slovene emigrants “is very similar”.

The number of immigrants and emigrants, however, is correlated with the performance of the economy, so in the years 2010-17, more or less the same numbers of people came to Slovenia as left it. In 2018, when the economy had finally recovered from the crash of 2008, the numbers of immigrants soared.

Today it is far from clear how long the legacy of coronavirus will last but it seems inevitable that a shrinking economy will again lead to a declining number of immigrants. Kajzer said anecdotal evidence suggests “a lot” of foreign workers had already gone home as the lockdown began.

Differing projections predict that by 2050, unlike all the other countries of former Yugoslavia and almost all of those of former communist Europe, Slovenia’s population will not fall dramatically. It will either be a little higher or still hovering at around two million. What will be the same, though, is that Slovenes will just be a lot older.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN or ERSTE Foundation.

First published on 18 June 2020 on Reportingdemocracy.org, a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The article was produced within the framework of the Europe’s Futures project.

This text is protected by copyright: © Tim Judah. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures and graphics are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy