Ruling parties in the Balkans are suspected of using proxy donors to fill campaign war chests with cash from secret sources. How authorities respond is a test of their independence.

At first, they asked nothing in return. A local member of Serbia’s ruling party had helped her get a job as a teacher. She knew plenty of others who had found work at public institutions or companies run by people with ties to the Serbian Progressive Party. No shame in that, especially with unemployment rates approaching 15 per cent. As presidential elections drew near in the spring of 2017, the party invited her to weekly meetings. Aleksandar Vučić, Serbia’s then Prime Minister, was the Progressives’ combative candidate for head of state. Victory would hand his party its fourth straight win in presidential and parliamentary polls over six years and further cement Vučić’s position as the most powerful man in Serbian politics.

At one meeting, an official took the teacher aside and handed her cash: 40,000 dinars, then worth around 320 euros. It came from a large donation, the official explained, giving no further details. Would she donate it back to the party in her own name? “I just got the envelope with the money and the account number to pay it into,” she said. “Everybody knew what was going on when I went to the bank. They already knew how the payments were working. Later, I brought them a payment slip as proof I paid the money.” Fearing she might lose her job, the woman declined to be identified. She said she saw party officials ask others at meetings to make similar donations. “If I didn’t do it, someone else would, so what can I say?”

One of our investigations shows that hers was not an isolated case but part of a pattern by the Progressives of using proxy donors to disguise the true source of campaign gifts — illegal under Serbia’s law on the financing of political activities. While it was impossible to trace the provenance of cash suspected of being laundered through fake donors, the investigation found evidence of systematic flouting of the law by the party in this and previous elections. The party did not respond to requests for comment. The investigation also highlighted a culture of impunity. Anti-corruption authorities wanted prosecutors to launch criminal proceedings in relation to suspected illegal activity during elections in 2014, but not one person has been indicted, casting doubt on the independence of Serbia’s prosecution services. Analysts draw parallels with other former Yugoslav republics where political elites have taken over state institutions for their own benefit while choking off opposition.

In neighbouring Montenegro and Macedonia, authorities have long turned a blind eye to allegations of illegal financing of ruling parties through money laundering and other means. But graft fighters point to Macedonia as a case study in what can happen when prosecutors bare their teeth. Following a corruption scandal that brought down the government, Macedonia’s former prime minister and close associates are under investigation for using fictitious donors to launder cash. They have also been indicted for election fraud.

Mysterious list

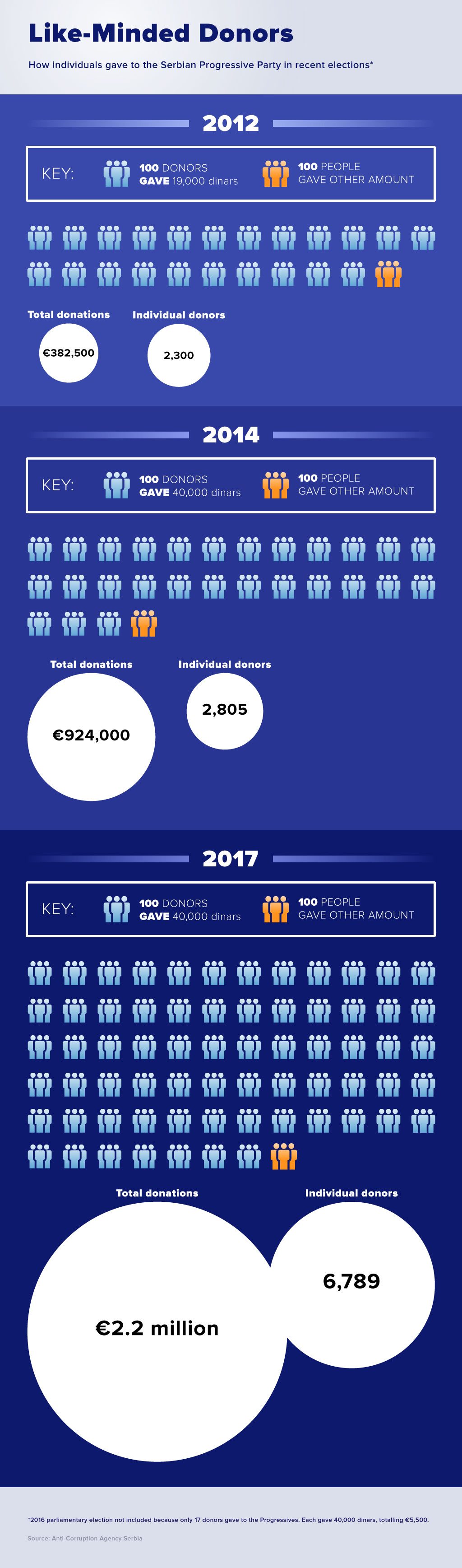

In Serbia, we tracked down the teacher and four others who admitted to being fake donors from a list of names published on the website of the Anti-Corruption Agency, ACA, the independent state body charged with policing the financing of political activities. Parties in Serbia are legally required to report campaign cash flows, including donations, within 30 days of any election. The agency then publishes donor names and amounts as part of its routine vetting of campaign finances. But this list was like no other. For one thing, 98 per cent of individual donors to the Progressives gave precisely the same amount: 40,000 dinars. So many, in fact, that it took the agency a week to enter the 6,789 names into its online database. There was nothing illegal in the sums. Under Serbian law, individuals can give political parties up to 20 times the average monthly salary, which was almost 385 euros in March. And unlike other countries in the region, Serbia has no limit on overall funds parties can collect for campaigning. But it is a criminal offence, punishable by up to five years in prison, to try to hide the source of donations.

“They called one night and told me to come to the party office.”

Many people contacted by us declined to comment, but five independently confirmed they were given 40,000 dinars by party officials to donate to the Progressives in 2017. All wished to remain anonymous. “They called one night and told me to come to the party office,” one man, 27, said. “There were no more explanations on the phone.”

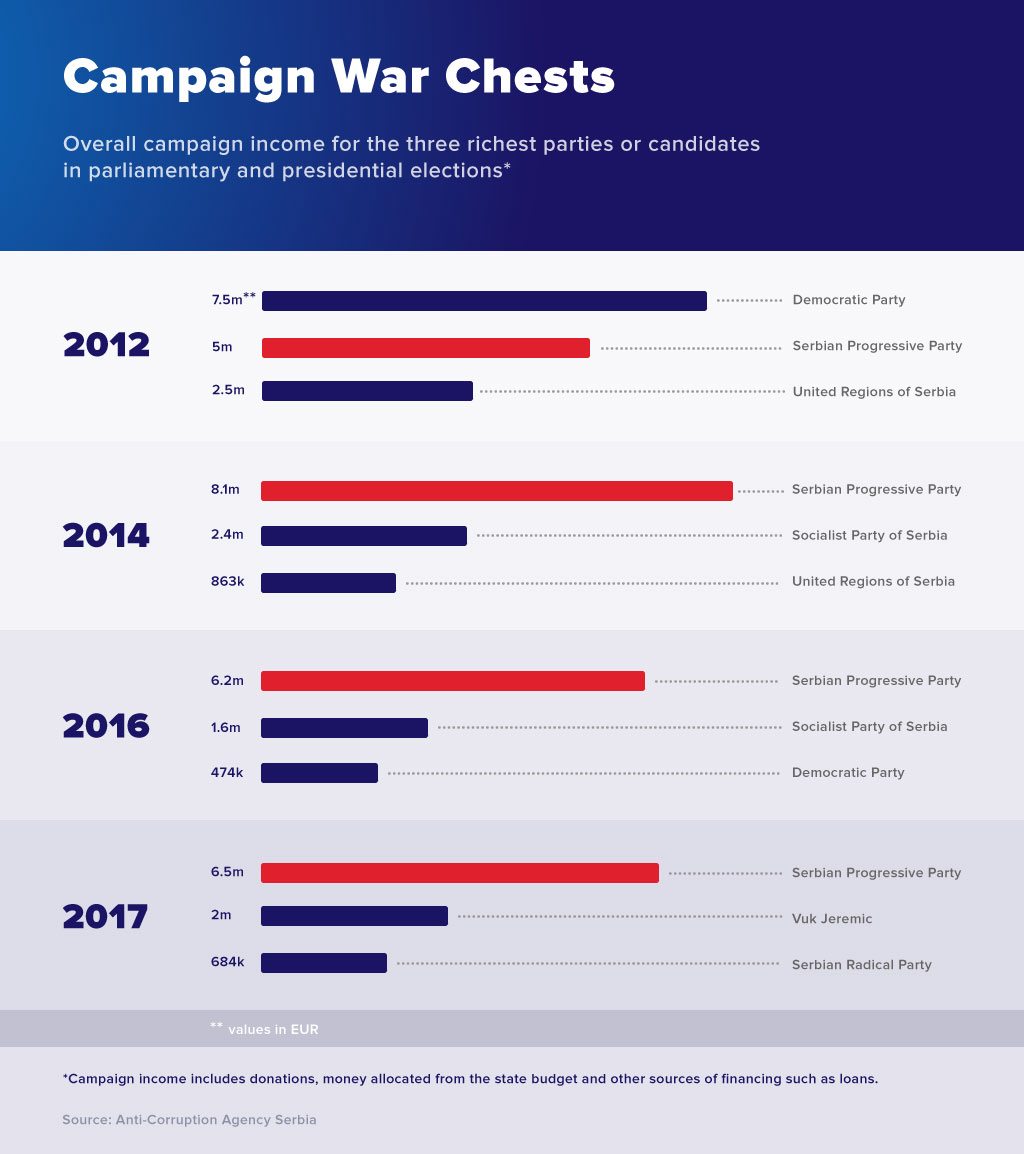

Collectively, the Progressive’s army of curiously uniform individual donors contributed more than two million euros to Vučić’s campaign — more than a third of his overall war chest of 6.5 million euros. Most of the rest came from the state budget in line with election rules. The total was considerably more than the combined income of all 10 other candidates, which came to just over 4.3 million euros. That kind of spending power allowed the Progressives to mobilise mass rallies, plaster the country with billboards and smother newspapers with advertisements. In fact, the party spent 83 per cent of its campaign finances on advertising alone – in excess of 5.3 million euros, more than the combined total spending of all other candidates.

Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence 2017: infographic Campaign War Chests

‘Clean as a whistle’

In the end, Vučić won with a crushing 55 per cent of votes after an election that monitoring groups said was marred by vote-buying, intimidation and control of the media. The second-placed candidate got 16 per cent. “Particularly widespread … were reports of pressure on employees of state and state-affiliated institutions to support Mr Vučić and secure, in cascade fashion, support from subordinate employees, family members and friends,” the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe said in a report published in June.

At 10.25 pm on April 2, shortly after the results were in, Vučić stood at a podium at Progressive Party headquarters in Belgrade’s business district. The man who had served as information minister for Serbian strongman Slobodan Milošević in the late 1990s was no stranger to soundbites. His victory was “clean as a whistle”, he told journalists. The next day, thousands of demonstrators, mostly young people, took to the streets in cities all over Serbia, blowing whistles and banging pots. “Vučić, you stole the election,” protesters chanted. “Do you sleep well, Kim Jong Un?” one placard read, comparing Vučić to North Korea’s leader.

Demonstrators compare newly elected Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić to North Korea’s dictator. The sign reads: “Do you sleep peacefully Kim Jong Un?” © Beta

Serbia’s Protest Against Dictatorship, as organisers called the demonstrations, was reminiscent of recent unrest in Montenegro and Macedonia, where protesters called for the resignation of long-time rulers, accusing them of corruption, abuse of power and election fraud. The protests also had echoes of mass demonstrations in 2000 that brought down Milošević following disputed elections. But unlike those displays of anger, anti-Vučić protests petered out after a couple of weeks.

“Vučić you stole the elections!”

Although the role of president is largely ceremonial, critics say the result paved the way for Vučić to tighten his grip on power in a country where political patronage and clientelism go hand in hand with creeping authoritarianism. “The results have destroyed the institutions of parliament and government, which are now functions of the president,” said Zoran Gavrilović, director of the Bureau for Social Research, a Belgrade-based think tank. With parliamentary elections not due until 2020, Vučić and the Progressives now look unassailable.

Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence infographic: Like minded donors

Financial fingerprints

As the face of Serbian hopes of joining the European Union, Vučić has projected an image of stable leadership in a turbulent region even as critics at home accuse him of rigging the system in the ruling party’s favour. He became prime minister in 2014, a watershed year in which the Progressives won the first absolute majority in parliament since the ousting of Milošević. Vučić had previously served as defence minister and deputy prime minister following 2012 elections that made the Progressives the ruling party. Suspected money laundering marred both those polls. Other parties had suspicious donors too, including companies that gave generously despite posting losses. But the Progressives were unique in having thousands of contributors who gave exactly the same amounts.

These sums became the financial fingerprints of suspicious activity during Progressive campaigns. In parliamentary and presidential elections in 2012, 98 per cent of 2,300 individual donors all gave 19,000 dinars. The sum of choice was 40,000 dinars in later campaigns. In 2014, 95 per cent of more than 2,800 donors gave that amount, while in 2017 the proportion was 98 per cent of almost 7,000 givers. The exception was parliamentary elections in 2016, when the Progressives received just 17 donations, all of 40,000 dinars.

Most campaign cash that year came from the party’s own resources, following a change in the law allowing the mixing of regular and campaign funds. The ACA has long had reason to be suspicious of Progressive donors. In 2012, the agency flagged 33 donations to the party from people who were on state benefits, according to a report it published on its website after the election.

“Certain contributions of these people amount to 50 per cent or more of yearly welfare received,” the agency said, triggering speculation that the oddly munificent welfare recipients were actually surrogates for secret donors. Our investigation revealed the agency also had serious concerns about the 2014 campaign after a tip-off from a separate state body, the Administration for the Prevention of Money Laundering, responsible for financial intelligence.

Four days after the election, the ACA learned of 135 bank transactions in which people had deposited 40,000 dinars into their accounts and immediately transferred the same amount to the Progressives as donations. Almost three years later, in March, the ACA submitted a report to prosecutors urging them to launch criminal proceedings in relation to the transactions, worth some 46,000 euros.

The agency suspected the donations were “actually from illegal activities, among others money laundering”, it said in the report, seen exclusively by BIRN. The ACA’s report also highlighted two suspicious bank transfers to other parties, one worth 5,600 euros to the Socialist Party of Serbia and one worth 690 euros to the United Regions of Serbia. The report urged prosecutors to take action regarding those transfers as well.

The United Regions of Serbia is now defunct and the Progressives and the Socialists did not respond to questions about the specific contents of the ACA’s report or any potential charges relating to the 2014 election. The Progressives also did not respond to questions about the five self-confessed proxy voters in 2017 and the ACA’s discovery of donors who were on welfare in 2012.

Allegations in Montenegro

Allegations of money laundering of campaign cash have long blighted politics in Montenegro, where the ruling Democratic Party of Socialists, DPS, have held power for more than two decades under the leadership of Milo Đukanović.

Critics describe Serbia’s tiny neighbour and EU hopeful as a fiefdom run by political elites. They accuse the DPS of misuse of state funds, abuse of office, election fraud and vote-buying, all denied by the party. In October 2016, the DPS scored its seventh straight victory in elections overshadowed by an alleged Russian-backed coup plot and deep divisions over Montenegro’s path to NATO membership, which it achieved in June. Prosecutors are investigating opposition leaders for possible involvement in the alleged coup. They are also looking into allegations that Nebojša Medojević, leader of the main opposition alliance, the Democratic Front, laundered money to finance the coalition during the 2016 election, which he denies. Critics say prosecutors are less eager to investigate allegations of similar money laundering by the ruling DPS, which is still led by Đukanović although he stepped down as prime minister last October. In 2011, local media published the names of people who denied they had given money to the DPS although their names appeared on the State Election Commission’s list of donors. Prosecutors started investigating the case in early 2012, but only after an anti-corruption group called MANS filed a criminal charge against the party for possible money laundering. Five years later, nothing has come of the case. The special state prosecutor’s office declined to comment. Meanwhile, the allegations have not discouraged donors from giving to the DPS. In the 2016 election, individual donations accounted for half of the party’s campaign war chest, amounting to some 680,000 euros.

Political interference?

Asked about the agency’s three-year delay in submitting the report about the 2014 election to prosecutors, Božo Drašković, a former ACA board member, blamed “political influence”. “Bear in mind that people in the ACA take their cue from the board,” he said. “If the board is independent, it would put pressure on the director and others to get the job done, but if it’s under political influence, people risk losing their job. That’s the essence of the whole thing. And then they delay, in my experience.”

Jelena Đorđević, an adviser at the ACA’s Department for the Control of Financial Statements of Political Subjects, said the agency had no power to investigate or examine witnesses, making it hard to initiate criminal charges itself. For that reason, it had sent its findings to prosecutors, she said. The prosecutor’s office said it had sent the report back to the ACA for further checks. It declined to comment further. As of publication, it had not pressed charges.

Nemanja Nenadić, programme director of corruption watchdog Transparency Serbia, said prosecutors had a duty to scrutinise suspicious donations to find out where the money came from. “This has never been done and there is no plausible excuse for the failure of the prosecutor’s office to do so,” he said.

In Serbia, public prosecutors are nominated by the government and confirmed by parliament, meaning their election depends on the ruling majority. They serve terms of up to six years and can be re-elected almost indefinitely. Unique in the region, the system is a “political process par excellence” that opens the door to obstruction of justice, said Radovan Lazić, president of the board of Serbia’s guild of prosecutors. “If prosecutors know they will after a certain period of time be elected again by politicians, they have no reason to find fault with them,” he said. “A prosecutor is even quite motivated not to find fault so he can get a new mandate.”

Serbia is ranked 118th out of 137 countries in terms of judicial independence on the World Economic Forum’s latest Global Competitiveness Index, just below Bosnia, Mauritania and Mozambique. World Bank analysis in 2014 showed that 25 per cent of judges and 33 per cent of prosecutors in Serbia thought the justice system was not independent.

When prosecutors are independent…

Across the border in Macedonia, prosecutors know a thing or two about political interference. But some are biting back, and graft fighters say their example offers inspiration for anti-corruption investigators in Serbia and elsewhere. In Skopje, public prosecutor Lence Ristoska recalled one night in 2016 when she and colleagues were working late at the office of the new Special Prosecution, SJO, set up to investigate high-level crime. They heard a commotion outside and went to the window. These were unsettling times in Macedonia. The SJO had been created as part of an EU-brokered crisis agreement following a wiretapping scandal that had paralysed the country. They saw a crowd of people shouting: “Bravo!” and “Way to go!”

Members of Macedonia’s new Special Prosecution, set up to investigate high-level crime, give a news conference in Skopje. Prosecutor Lence Ristoska is second from the left. Photo: © BIRN

“It was so encouraging to see that somebody finally took notice and recognised that what we were doing was the right thing, that we were not alone in this,” Ristoska said. “That’s when we realised there was no going back for us.” The people outside the window were protesters demanding the resignation of Nikola Gruevski, then Prime Minister and leader of the ruling party known by the acronym VMRO DPMNE.

It was at the height of months of unrest dubbed the “colourful revolution” after the paint demonstrators splattered on public buildings and monuments.

Fury erupted in 2015 after opposition leader Zoran Zaev claimed Gruevski’s government was behind the illegal wiretapping of 20,000 people and other crimes including election fraud, which Gruevski denies. Among other things, the SJO is investigating allegations that Gruevski and 10 associates financed the former ruling party through money laundering.

Codenamed “Talir” [silver coin], the money-laundering investigations cover the period 2009-2015. Prosecutors suspect the party laundered at least five million euros using fake donors. Transparency Macedonia had repeatedly highlighted concerns about money-laundering to prosecutors, the state auditor and tax authorities. Nobody took action, partly because people whose names turned up on donor lists refused to confirm they had been part of scams.

“People were reluctant to stand up in public for fear of losing jobs, or their shops being closed down or [of being] punished in other ways,” Slagjana Taseva, president of the anti-corruption group, said. “Their rule was the rule of fear, literally.”

A riot policeman stands by a building in Skopje splattered with paint during Macedonia’s “colourful revolution” in 2015. Photo: © BIRN

This article was produced as part of the Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation and Open Society Foundations, in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.