On the biggest lake in the Balkans, rangers say it is easier to catch a drug trafficker than a poacher amid warnings of ecological disaster.

Some do it the easy way on Lake Skadar, poking electrodes into the water to zap carp and eels with 110 volts from a transformer hooked up to a car battery. As the stunned fish bob to the surface, they scoop them into the boat. Others unfurl nets and stake them to the muddy bottom. Tell-tale rows of sticks dot the shorelines straddling Montenegro’s southern border with Albania. But for one Montenegrin poacher on the biggest lake in the Balkans, the old ways are best. What used to be done with lanterns is today done by flashlight.

In a flat-bottomed boat under the cover of darkness, he shines a torch into the shallows where carp nestle among the reeds. When he spots one, he hurls a three-pronged harpoon. He rarely misses and can skewer more than 100 in a night. “If I couldn’t kill a fish or two, I’d have to kill someone,” the burly poacher told the author with a smile. Declining to be identified, the 45-year-old father of three explained how his family has spearfished for generations in the lakeside Zeta region just south of Podgorica.

Harpoons are strictly illegal on Lake Skadar. So is fishing with electricity, spearguns or dynamite. And all means of fishing, including rods and nets, are outlawed during the spawning season between mid-March and mid-May. Not that the ban deters the poachers. Locals who live in the national park on the Montenegrin side of the lake joke that at night the area becomes a virtual Las Vegas of twinkling flashlights. While poachers risk fines of up to 20,000 euros and three years in jail, few are ever prosecuted.The poacher from Zeta said rangers had caught him several times and let him go.

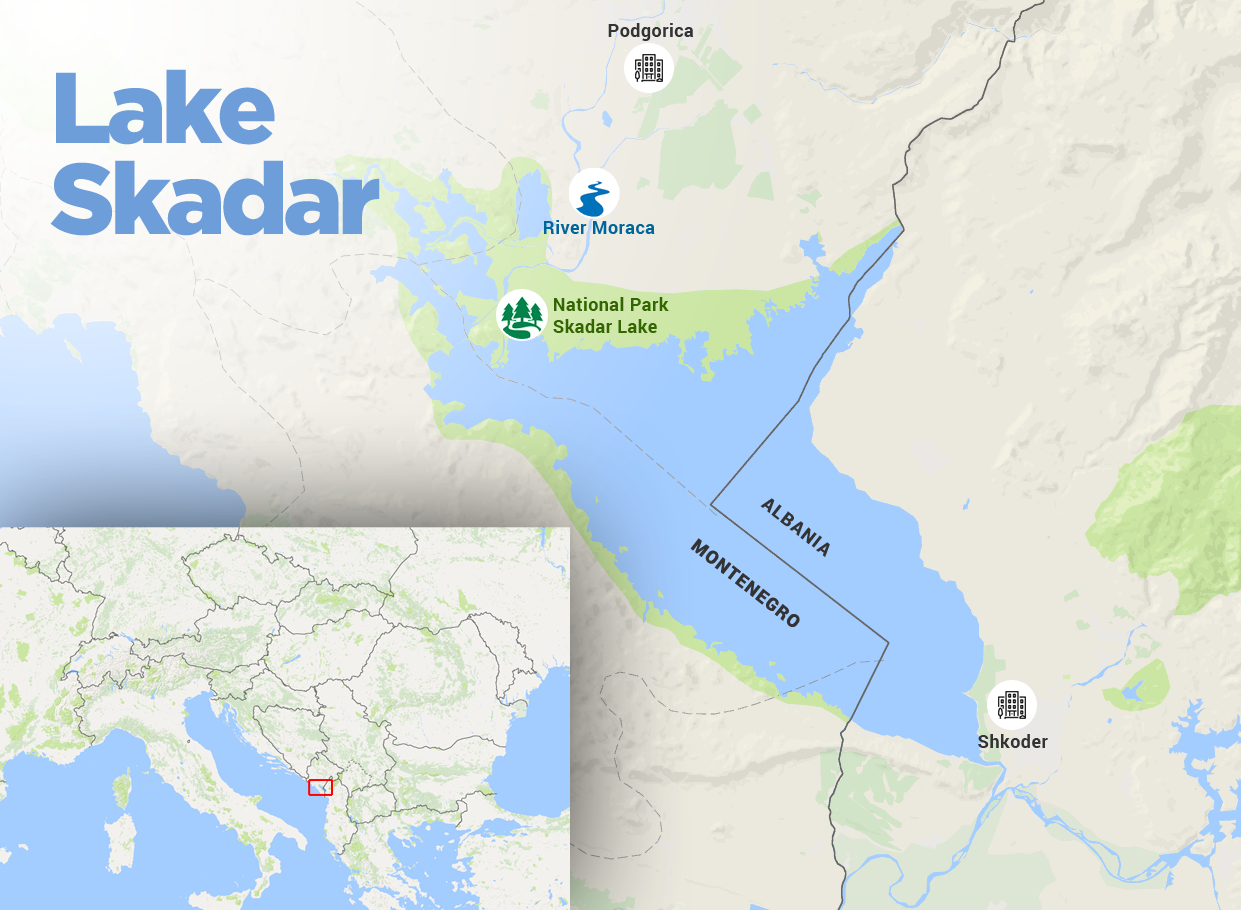

“They’re mostly people from this area,” he said. “Sometimes, some of them join me.” Conservationists warn of ecological disaster in one of Europe’s last freshwater wildernesses as poachers stun, spear, hook and net millions of euros worth of fish each year with almost total impunity. Much of the haul is sold in the nearby markets of Podgorica and the lakeside Albanian city of Shkoder, where Lake Skadar carp is considered a delicacy. “Most people have this vision of Lake Skadar as a giant ATM machine in which instead of entering a PIN code, they can steal as much fish as they like,” said Danilo Mrdak, an ichthyologist and professor of biology at the University of Montenegro in Podgorica.

A poacher takes to Lake Skadar as night falls. Photo: © Darko Vučković

While local fishermen have long seen the lake as a birthright to be exploited, environmentalists say the biggest threat to fish stocks is the increasingly organised nature of poaching and the corruption that allows it to flourish.

In a region known as a major smuggling route during Yugoslavia’s violent breakup in the 1990s, they say tech-savvy criminals find it pays more to catch fish than to traffic guns or narcotics. It is also easier to get away with. “It’s more difficult to catch a poacher on Lake Skadar than to arrest a drug dealer,” said Drazen Ivanovic, the chief ranger in charge of policing the Montenegrin side of the lake, which is a protected national park.

“With technology, everyone is connected and information spreads around the lake at lightspeed. It’s taken on the form of organised crime. Unfortunately, we’re hardly able to scratch the surface because we’re limited by resources, equipment and men.”

The legal framework

Principles of conservation are enshrined in Montenegro’s constitution and — on paper at least — the country has robust laws for protecting the environment, regulating fishing and managing its national parks. Two international treaties also protect Lake Skadar: the Ramsar Convention on safeguarding wetlands and the Council of Europe’s Bern Convention on nature conservation. Montenegro’s side of the lake — two-thirds of the water — is managed by the Public Enterprise National Parks of Montenegro, NPCG, set up in 1993 under the provisions of the Law on National Parks and Law on Nature Protection. But the task of thwarting poachers falls to just 13 rangers working for the NPCG’s National Park Protection Service Department, run by Ivanović. At any one time, only four gamekeepers are out on the 600-square-kilometre lake.

“There are as many as 10 Viber [mobile messaging application] groups dedicated to monitoring and reporting every step we make,” Ivanović said, lamenting his team’s outdated boats and equipment. “We need night binoculars. And above all, we need to be armed.”

While gamekeepers are not allowed to carry weapons, there is no shortage of guns in a region synonymous with arms-smuggling during Yugoslavia’s dying days in the 1990s.

As war and sanctions compounded hyperinflation in Serbia and Montenegro, the last two republics of Yugoslavia after its breakup in 1992, the gunrunners of Lake Skadar found it profitable to smuggle other commodities across the lake from Albania: cigarettes, fuel, clothes and drugs. This continued until the fall of Serbian strongman Slobodan Milošević in 2000, after which smugglers started turning to poaching, locals and conservationists say. By the time Montenegro declared independence in 2006, illegal fishing was a fully fledged criminal industry.

Lake Skadar on the map

Ivanović estimates that poachers plunder between seven and nine million euros worth of fish from the lake each year in Montenegro. “I’m not happy with the number of reports filed for criminal proceedings or the quantity of poaching equipment confiscated,” he said. “But bearing in mind how few people I can rely on, I can’t complain.”

In the first six months of 2017, authorities pressed criminal charges against 17 people after rangers confiscated equipment including a transformer, a shotgun, two boats and three electrodes, the NPCG said. The public company also initiated misdemeanour proceedings against 20 people after confiscating 42 nets, three harpoons and a number of lamps and gas containers. Such actions bring little comfort to conservationists worried about declining fish stocks.

A report published in October by Germany’s international development agency, GIZ, highlighted a number of threats to fish protected under national and European conservation legislation. “Economic species such as carp or bleak are exploited haphazardly and sometimes illegally with little if any knowledge on the status of stocks and maximum sustainable yields,” the report said.

Mrdak, the ichthyologist from the Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics at the University of Montenegro, estimates that poaching accounts for 60 per cent of all fishing activity on Lake Skadar. In his view, electrofishing is the biggest enemy of the 30 indigenous and more than a dozen non-native fish species that live there.

Montenegrin ichthyologist Danilo Mrdak. Photo: © Mladen Ivanović

In 2013, he led a study that found the lake’s population of bleak had fallen by 90 per cent due to overfishing. He lobbied for a year-round ban on catching the small, silver fish, to allow stocks to recover. Last year, the NPCG introduced a moratorium on bleak fishing, although ichthyologists will not know until next winter if it has worked. In the meantime, Mrdak wants a year-round ban for carp. “Over the last few years, we’ve observed that larger carp specimens are becoming extremely rare, even for professional fishermen, which indicates that the species is under high pressure and therefore there’s little chance for a fish to survive long enough to grow before being caught,” he said. “Indirect proof of this is the extremely high price for large carp specimens.”

Thriving market

Locals say the tastiness of Lake Skadar carp comes from the purity of the water flowing into the lake from the northern mountains of Montenegro via the river Moraca. Outside Podgorica’s biggest indoor market, the author saw vendors illegally selling carp from the back of trucks during the height of the spawning season. Still alive in plastic bags, some with harpoon wounds, the fish cost around five euros a kilogram, at least double the price at other times of the year when fishing is legal. Big carp can go for as much as 100 euros.

Poachers from tightly knit communities in the Zeta region described a thriving trade that relies on trusted middlemen to make the 20-minute drive between the lake and Podgorica while the fish are still flapping. One said a skilled poacher could earn 1,000 euros a month through electrofishing. The average monthly salary in Montenegro is around 500 euros. “I’ve been using the same secure dealer for 10 years,” he said. “He probably sells to restaurants and market vendors. He pays the best.”

The Fishing and Agriculture Inspectorate, part of the agriculture ministry, told the author in July it was monitoring markets and restaurants for illegal fish sales. But it said it had received no reports of criminal activity.

‘They never carry any personal documents so we can’t verify their identities’

Corruption allegations

The sight of the gamekeepers is not always a deterrent. According to activists and local fishermen interviewed by the author, the guardians of Lake Skadar are sometimes part of the problem. “The rangers are partly responsible for high rates of poaching,” said Željko Radenović, an angler and activist at the Carp Protect Team, a non-governmental organisation devoted to safeguarding fish stocks in Lake Skadar. “It’s usually based on nepotism or bribe-taking, and often they are themselves the poachers.” Radenović and fellow anglers from the Carp Protect Team keep watch over the lake and inform authorities whenever they see electrofishing. A long-time poacher told the author he had heard of illegal fishermen paying bribes to rangers or giving them a percentage of their sales — though he claimed never to have done it himself because he knows most gamekeepers personally. “Once they took a harpoon and some fishing nets away from my father, but they soon returned everything,” he said. “It’s dangerous only when a new gamekeeper comes along. But they lose the will to do their job very soon, after their first paycheque.” Rangers said they earned between 200 and 300 euros a month.

Out on Lake Skadar, there was plenty of evidence of lawbreaking. One chilly night in May, during the fishing ban, two rangers were on a midnight patrol near the mouth of the river Moraca, dragging illegal nets out of the water. Some nets were longer than 100 metres and full of carp. One net got tangled in the speedboat motor; it took an hour to cut it free with a razor. They said they had little hope of catching poachers red-handed since criminals usually slip behind reed beds in shallow water inaccessible to the rangers’ bigger boats at the first sound of their engines.

Sometimes gamekeepers can only look on helplessly as poachers, just metres away, taunt them from flat-bottomed fibreglass boats. Even if they catch them, there is often little they can do. “They wear miners’ helmets with flashlights and hoods so we can’t recognise them, and they never carry any personal documents so we can’t verify their identities,” said Radonja Maras, a garrulous ranger several months into the job.

On a daytime trip in a hired boat, the author saw poachers brazenly defy the fishing ban around Grmozur island, the site of a former prison on the northwest part of the lake near the town of Virpazar. In sight of ruins of the 19th-Century jail nicknamed the Montenegrin Alcatraz, they were setting nets and casting rods. On the nearby Gostilj river, poachers were throwing electrodes into the reed-filled water and scooping up fish after fish. When a rangers’ boat appeared in the distance, all activity stopped.

In 2013, the National Park Protection Service Department made headlines after it emerged that a ranger had submitted an internal report complaining that three colleagues had stopped him from confiscating a generator used for electrofishing. According to the memo seen by the author, the reason the rangers gave was that the owners of the generator were working for a powerful local businessman. None of the three rangers lost their jobs or were suspended, though one had his salary docked by 20 per cent for two months as punishment, according to the NPCG.

Ivanović, who took over as head of the department in 2016, is one of the few rangers not from the area. He comes from the Kuci region near the Albanian border northeast of Podgorica and now lives in the capital. Asked about allegations of corruption among gamekeepers, he neither confirmed nor denied the accusations but said he needed younger staff from outside the region who had a better understanding of ecological matters. “My level of trust is such that I have to use the same two or three men to cover the entire protected area, so they have to work overtime,” he said. Ivanović blamed officials at the NPCG for not grasping the challenges facing his department and said it would take at least 30 well-trained rangers to provide 24-hour protection on the lake.

The NPCG said that while it had not received reports of corruption among rangers, it recognised the need for more gamekeepers and would soon be hiring two more. It also plans to upgrade rangers’ equipment, including boats, GPS devices, binoculars and cameras, the NPCG’s communications office said in an email.

In early November, police arrested an alleged poacher after a tip-off. They said they caught 34-year-old Milorad Maras with a transformer, batteries, an electrode and a quantity of fish in his boat. They charged him with illegal fishing, which he denies. It turned out the man was the son of long-time ranger Milenko Maras, who had been on patrol on the same part of the lake shortly before the arrest. Maras said he had not seen any illegal activity and that his son must have been “framed”, though he did not say by whom. The NPCG said it would launch an investigation.

A traditional Lake Skadar boat is seen on the shore of the Albanian side of the lake. Photo: © Mladen Ivanović

‘Paradigm of society’

Across the border in Albania, Lake Skadar is managed by the Organisation for the Management of Fishing in Lake Skadar, OMP. Scandal has dogged the public company since BIRN reported allegations in 2014 that the OMP was running a protection racket for poachers who fish with electricity.

Arjan Cinari, head of the OMP, has always denied wrongdoing. Speaking outside his office in Shkoder, with panoramic views of the lake behind him, he reiterated that he and his men had nothing to do with illegal fishing or bribe-taking. “This has never happened,” he said. “It would be like letting the thief enter freely into our house.” Cinari said it had been an uphill struggle to change attitudes towards poaching among locals when he took the job a decade ago, but now most illegal fishing took place on the Montenegrin side of the border. “I found out that in Montenegro they use electrical power for poaching and transformers that can release 800 to 1,000 volts,” he said. He added that his rangers often see flashlights and evidence of electrofishing near Pothum, a Montenegrin border village on the northeast part of the lake.

‘It would be like letting the thief enter freely into our house’

Denik Ulqini, a biologist at the University of Shkoder, said poaching blighted both sides of the border equally. “I think we must produce assessments of fish populations for the entire lake and prompt the [Albanian] state to get involved in protecting the lake,” Ulqini said. Montenegrin head ranger Ivanović also disputed Cinari’s claim that the Albanian side had fewer problems. “We keep seeing night-fishing activity, poaching, flashlights, generators, all on their side,” he said. “Very often their poachers cross illegally into our waters and they mostly fish here, on our side.” The NPCG and OMP have no agreements for joint management of Lake Skadar, and the two organisations have only met twice since the Albanian government transferred stewardship of the lake to the OMP in 2014.

Both Albania and Montenegro are candidates for joining the European Union, and conservationists hope environmental issues will take centre stage during accession negotiations. In Montenegro, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development is working on amendments to laws on freshwater fishing ahead of talks on Chapter 27, the part of EU negotiations dealing with the environment. “The new legislation will improve on the current legal framework, expand the powers of rangers to protect fish, reform penal policy and introduce modern technology when it comes to the issue of permits and collection and processing of data for freshwater fishing,” said Deniz Frljukcic, an advisor at the ministry’s Directorate for Fisheries.

Jovana Janjušević, a member of an alliance of environmental groups known as Coalition 27, described illegal fishing as “a burning issue in the area of environmental protection where we haven’t noted any significant and systematic progress”. “Gamekeeper services need to be adequately equipped and inspections should be strengthened in terms of people and prevention,” she said.

For ichthyologist Mrdak, it all comes down to political will in a country plagued by corruption and abuse of power. “This is the paradigm of our society as a whole,” he said. “You can’t expect this to be an exception in a society where so many things go wrong.” He said too many people had their heads in the sand when it came to protecting one of the jewels of the Balkans. Standing at a lookout beside the lake, he pointed at the water and adopted a sarcastic tone. “If you look around, you can see for yourself the dolphins are jumping high and everything is just perfect,” he said. “There are more fish swimming in the lake than you can imagine.”

First published on 4 December 2017 on Balkaninsight.com.

This text is protected by copyright: © Ivan Čađenović. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Snow-capped peaks loom over the waters of Lake Skadar along the Montenegrin-Albanian border. Photo: © Darko Vučković

This article was produced as part of the Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation and Open Society Foundations, in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.