11 August 2020

Originally published

01 May 2020

Source

Poland was under martial law from 1981 to 1983. Life stood still, civil rights were revoked. A young Austrian woman of Polish extraction searches for clues about the event that shaped her parents’ generation.

I discovered something at the beginning of March, when the state of emergency brought on by the coronavirus became increasingly real. While politicians in Austria were talking about the greatest challenge since 1945, and no one could remember anything like what was going on, my Polish parents were all too familiar with some of the steps being taken. Lockdowns, bans on public gatherings, border closures, university closures, daily announcements by the government on the latest developments – they had experienced it all in Poland almost 40 years before.

Back then, it wasn’t because there was a pandemic. Their state of emergency, called stan wojenny (‘state of war’), lasted from 1981 to 1983. It was declared to suppress, track down and arrest the people involved in the Solidarność (Solidarity) movement that was founded in 1980, as well as other opposition forces. The government wanted to restore the real socialist “order” at all costs. If it couldn’t, the Soviet Union would restore it by force like it did in Prague in 1968 – at least that’s what General Jaruzelski claimed to justify his coup. Historians still debate whether what he said was true. His claim is debatable for other reasons too. Chief among them is the fact that the same military government that acted so authoritarian and menacing in the early eighties enabled Poland’s peaceful transition to a pluralistic democracy less than 10 years later.

I’m beginning to realise that I know practically nothing about that chapter in Polish history, even though its consequences have shaped my life. My mother left Poland at the first chance she got. It was 1991, and I was still a baby. She took me to Vienna because of the political events that started in 1981. We never talked about those events at our apartment in southern Vienna. I only remember that since I’ve been able to think my mother has always shouted “martial law!” with an almost manic energy whenever she mentions 1981, the year that my older half-sister was born. Could now, when the current state of emergency has refreshed her memory, be a good time to finally learn more about that era? What exactly happened back then, and how much did it dominate the everyday life of millions of people for one and a half years?

We never talked about those events at our apartment in southern Vienna. I only remember that since I’ve been able to think my mother has always shouted “martial law!” with an almost manic energy whenever she mentions 1981, the year that my older half-sister was born.

Here are the historical facts. The Polish government unexpectedly declared martial law late at night on Saturday, 12 December 1981. Starting at 6 am the next morning, a speech by General Wojciech Jaruzelski, the head of the party, the government and the army all at the same time, was aired on TV at the top of every hour. It was one of the few times Jaruzelski appeared publicly without the dark sunglasses he was forced to wear after becoming snowblind while doing forced labour in Siberia. A 21-member Military Council for National Rescue (abbreviated in Polish as WRON), led by Jaruzelski and composed of admirals and generals from his staff, took over the administrative aspects of the state of emergency.

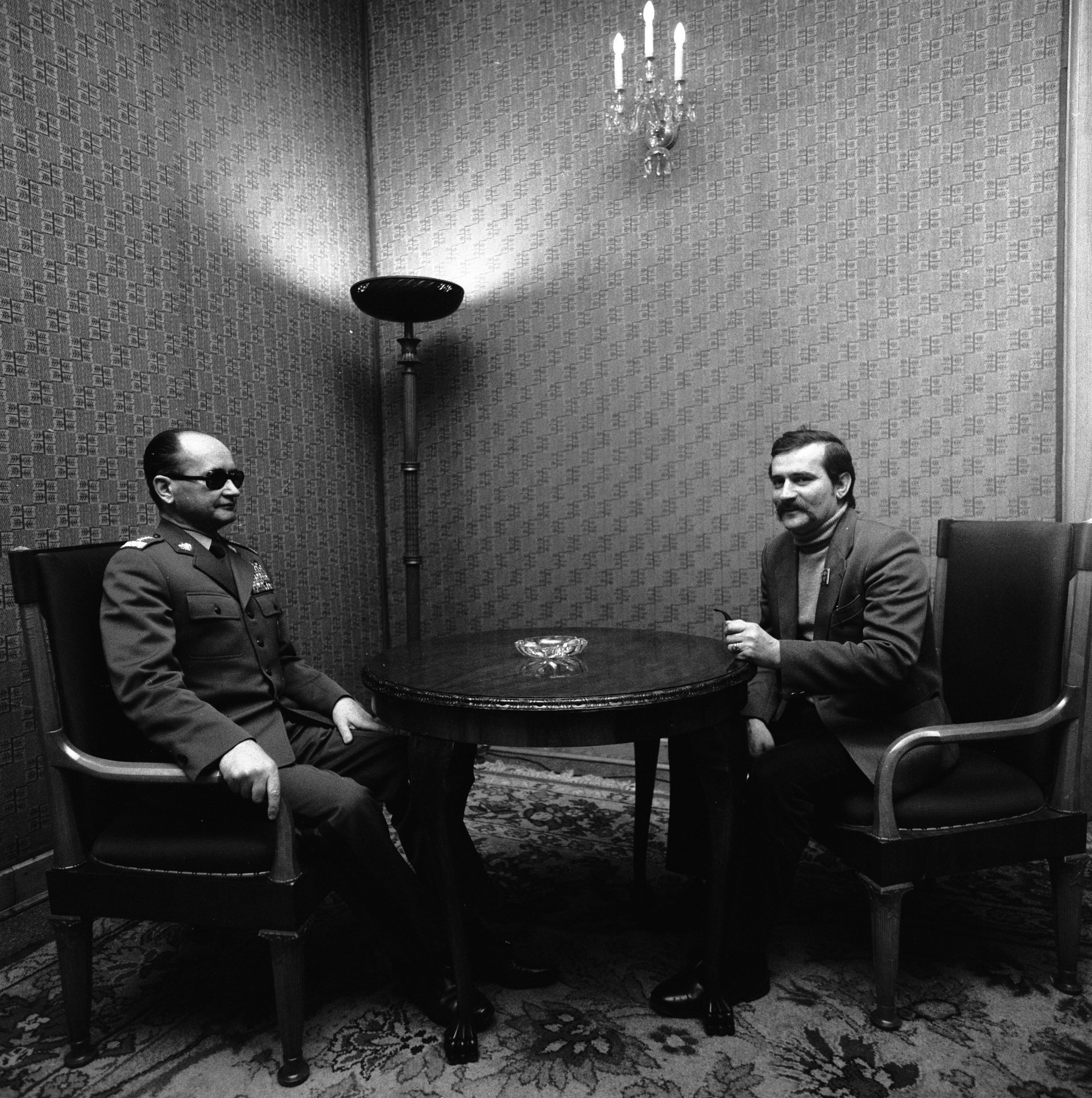

On March 10, 1981, General Jaruzelski (left) and the chairman of Solidarność Lech Wałęsa met for a discussion in Jarzelski’s office. Wojciech Jaruzelski, who back then was the chief of the party, government, and army at the same time, was mostly wearing dark sunglasses, which he needed because of his snow blindness caused by forced labor in Siberia. Photo: © Witold Rozmyslowicz / PAP / picturedesk.com

70,000 soldiers, 30,000 ZOMO riot police sourced from militias, 1,750 tanks and 9,000 vehicles were allocated in the run-up to this military operation, which had been kept top secret for a year while it was being planned. (Its code name at the Political Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was Operation Z .) They all launched swiftly in order to arrest thousands of members of the opposition, seal off cities and set up checkpoints across the country.

The rules they imposed included a ban on all demonstrations and strikes, closing national borders and restricting people’s movement to their own residential area, a police curfew from 10 pm to 6 am, checks and censorship of postal correspondence, allowing the military to search any suspect and closing all cultural institutions and universities. In addition, they banned the freedom of the press and large gatherings and took control of all radio and TV stations as part of Operation Azalia, which included cutting all telephone lines – making it impossible for people to contact the fire department or rescue workers for the next 29 days.

I didn’t begin to understand what all of this meant for people’s lives until my mother started telling me what she remembers from that time. Speaking to me on the phone from her house in the small town of Gänserndorf, Austria, she says she was luckier than she could have been when events began to unfold on Saturday night and all day Sunday. She was 21 years old and probably would have faced an interrogation, at the very least, for the flyers and books that were confiscated from her desk at her workplace – had she not been nine months pregnant.

As she was getting ready to go to work on 13 December like any other day (Poland didn’t have maternity leave back then), she arrived to find the doors to the office bolted shut. “I was an administrator at a library in Warsaw that was owned by Caritas”, says my mother, Elżbieta Dyk. “The militia forced its way into Caritas, confiscated the whole library, locked up my desk and shut everything down. I was right at the source for many different banned books. We had a lot of things from France, Solidarność flyers, magazines, packages – none of which had come through the official delivery channels. My job was to catalogue and document everything in the library. Other people took care of circulating the material because I was pregnant.”

She tells me about tanks on empty streets and colleagues who were arrested or went into hiding. It was hard for her to find out what was happening because the phone lines were cut and no one could call anyone, plus government TV was the only source of information. “No one knew where we were headed. All we knew was that our country was closed. What scared normal people like us the most was the possibility of a war breaking out. Everyone believed it was only a matter of time before Russian tanks would arrive and start shooting. At the time, I thought the communists probably didn’t know any other way to handle the situation than to just strike us down. I thought the only way they had to deal with us was to destroy us.”

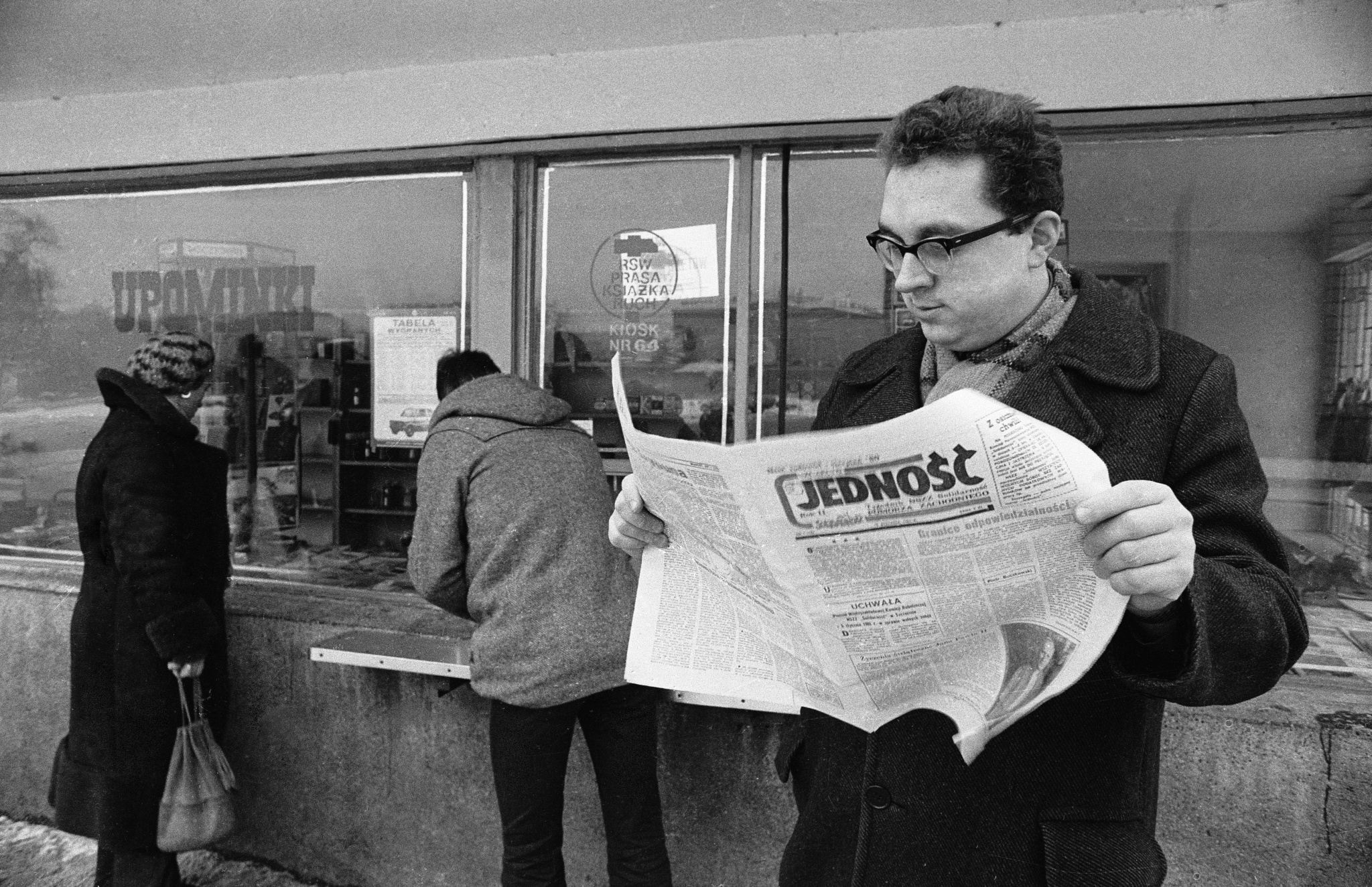

A man reads the first edition of the weekly magazine “Jedność” (“Unity”), which was published on January 9, 1981, with a circulation of 100,000 in Szczecin, Koszalin and Gorzów. Photo: © Zbigniew Jodkowski / PAP / picturedesk.com

My older half-sister Anna was born five days after martial law was declared. It was a particularly harsh winter; the snow was knee-deep on Warsaw’s streets. My mother had just moved in with her mother in the suburbs in order to be able to finish her engineering degree with her new baby. It took nearly three hours for her to walk to the hospital where she was planning to give birth. “The staff at Warsaw’s largest hospital in Mokotów sent me away twice when I showed up having contractions. They said they had been ordered to keep all of the beds available. It’s like what they’re saying now because of the coronavirus, that you should only go to the hospital if it’s really serious. But the toughest part was the complete lack of transportation – nothing was operating, and I didn’t have a car or much money. Besides, only the military and politicians had a permit to buy fuel. It’s the worst thing you can possibly imagine – you’re standing there in need of help, and all they tell you is they can’t do anything because they have to keep the bed available for other people.”

My mother and her friends had high hopes for the Solidarność trade union when it was founded. She says it gave them a sense of having something in common, a sense of belonging and possibility. The country’s economic situation had been getting worse even before 1981. This led to a wave of strikes and demonstrations. The resistance organised and eventually formed Solidarność in August of 1980. Of the 35 million people living in Poland at the time, 10 million signed up to become members. It wasn’t something you could ignore. It was huge, actually.

That’s why the state of emergency in 1981 was such a painful turning point for my mother and people like her. “Before they declared martial law, we walked home from work along the train tracks singing joyful songs together. I thought that we had to grit our teeth and fight for a better tomorrow even if it meant eating stale bread with sugar. That all changed after 13 December; it seemed like someone else took control. Once again, I found myself in a country where officials laugh cynically in my face when I go to beg them for my mother’s pension payment. A country where chaos reigns and only the people who have money and access to the black market can go home with 20 kilos of butter. And people tell you, ‘You were the one who wanted a child. It’s your job to figure things out.’”

This led me to wonder who those people were that my mother was talking about, the ones with 20 kg of butter. The ones who didn’t have to stand in line at 4 am like everyone else in the hopes of getting a ration of meat in the shops. Who didn’t have to plead for care packages coming in from abroad that the church distributed. Granted, enormous amounts of aid were mobilised through private households – around 30,000 care packages arrived in Poland from West Germany alone between 1981 and 1983 – but it was simply not enough for everyone.

I call my father, Piotr Dudziński, who has lived in Warsaw all his life, except for a few years that he spent in Vienna in the 1990s. As always, he laughs when I curiously ask him about episodes from his life that sound like they’re straight out of an absurd novel. I’ve known for a long time that my father is street smart, as the Americans say. He knows you can’t always take rules and laws so seriously, and he usually comes away without a scratch. But I’m still flabbergasted when he tells me about forging food tickets with the printing press of the largest daily newspaper in Poland that was still allowed, copying dollar vouchers (a type of foreign exchange currency for use inside Poland), and smuggling live piglets in the boot of his car.

“Martial law? Well, you know, it wasn’t much different from before. You just had to know the right channels to go through to get your concerns taken care of,” he says casually, without the slightest hint of self-importance. On the contrary, his memories of that time are so rosy that he’s almost a little embarrassed given how some people experienced it, like my mother, who parted ways with him a long time ago and whom he didn’t get together with until afterwards.

In 1981 my father owned a small café that was attached to a government-owned tennis court. Like many other bars and restaurants, his business was the perfect front for ordering and reselling large quantities of food. In other words, it was a trading post and a meeting place for people in the know. “The problem wasn’t that people didn’t have money – after all, everyone worked under the table to earn a little extra on top of their government salary. The money was there, and the people at the top knew it and wanted it. It was just hard to find the goods.”

So that’s what my father decided to become an expert in. “It went down like this. I would meet my friends at a hotel for breakfast, and we would talk about what we needed to get – fuel, sugar, meat, Coca-Cola – and then I headed out to the back of the indoor market and knocked. I have to say, the only problem I had back then was that all the bars closed at 10 pm and I couldn’t spend the whole night at my favourite dance club. But I did manage to get a permit that let me stay out until midnight.”

Then he talked about his neighbour, whose job it was to announce the news before the state of emergency. The WRON put a uniform on him to sort of make him look like a soldier, and then they let him read the news. We laugh. What a ghastly farce.

And the piglets? “They were well behaved. They never caused me any problems. I drove my VW Golf to the edge of the city, picked them up and took them to my friend’s apartment. He didn’t have hot water but he knew how to slaughter a pig. The militias hardly ever stopped me. I got caught once though, when I had over 100 kilos of sugar in the trunk. You should’ve seen the look on their faces. Of course I had to go to the station with them and pay them plenty of hush money. People were really itching for meat and stuff like that. It really was a hard time for most people. Everything was rationed. Like they only gave you 20 bottles of vodka for a wedding!” Only 20 bottles of vodka. A depressingly small amount of alcohol for a Polish wedding.

But sugar, meat and fuel were not the only goods people wanted. Books were in demand too, especially the ones with the infamous grey jacket. I’m talking about the editions from the culture and politics magazine Kultura, which were published first in Rome and then in Paris. It was one of the main publications of expatriate Poles, and it enjoyed a large readership within Poland.

“Looking back today, it’s really hard to imagine Poles getting so excited about those grey book jackets,” says Danuta Stołecka with a smile. In 1981 she was a Solidarność member who worked on the editorial board of a magazine that the movement published in Wrocław.

The Jodła (fir tree) campaign resulted in a total of around 5,000 people being arrested and sent to about 50 different internment camps throughout Poland in the span of just a few days.

Danuta wasn’t as lucky as my mother. She was arrested on 13 December 1981 and held until July 1982. The Jodła (fir tree) campaign resulted in a total of around 5,000 people being arrested and sent to about 50 different internment camps throughout Poland in the span of just a few days. During the course of the state of emergency, this number grew to about 10,000 people, including a large percentage of national and local protagonists from Solidarność, members of democratic movements, intellectuals and union leaders.

“It’s exciting to be Polish” says the board behind the windshield. The chairman of Solidarność Lech Wałęsa sits in the passenger seat and Mieczyslaw Wachowski at the wheel of the Fiat 125p, March 1981. Photo: © Jerzy Kosnik / PAP / picturedesk.com

Danuta was first put in a regular prison along with other women then moved to an internment camp, then another. She remained in confinement until general amnesty was declared for women on 22 July 1982, the National Day of the Rebirth of Poland. She wasn’t offered any legal assistance during those six months or even told how long she could expect to be in confinement. Yet Danuta describes the internment camp as a sort of “golden cage” compared to the conditions in which most prisoners were kept. “I was held in a building that used to house the Radiokomitet, a party institution that managed radio and TV programming. Yes, we were four women in a two-person room, but we had our own bathroom and access to two huge terraces surrounded by a beautiful landscape. We just couldn’t leave.”

Danuta and the people held with her were interrogated again and again. But she always remained silent, even though they offered to let her out early several times if she would sign a declaration of loyalty to the government. She still had to regularly go back into confinement for 48-hour periods after she got out. “Every month there were ‘jubilees’ to celebrate the start of martial law, and they were always accompanied by protests. To prevent us from taking part in them, they would lock me and other people up in advance.”

In 1984 Danuta Stołecka left Poland with a passport that would not allow her to return – they wouldn’t give her any other kind – and moved to Vienna. From there she worked with a group called Solidarity for Solidarność until communism fell. Her Polish friends supported her with money, food and materials for underground print shops. Danuta’s main strengths, however, were the coveted works of authors who had been banned in Poland and publications by historians. All of that prohibited literature arrived in Poland through a tight network of contacts and, of course, Danuta’s apartment in Vienna.

The state of emergency ended on 22 July 1983, but the repressive social climate remained in Polish society until the fall of communism in 1989.

The state of emergency ended on 22 July 1983, but the repressive social climate remained in Polish society until the fall of communism in 1989. Ultimately, through circuitous routes, the commitment of Danuta, my mother and millions of others like them succeeded in bringing change to Poland. In February 1989 there was a roundtable where General Jaruzelski and the leader of Solidarność, Lech Wałęsa, signed an agreement allowing the trade union to resume operations and prepared the first “semi-free” Polish parliamentary election. The rest is history. Wałęsa became the first freely elected Polish president of the post-war era in 1990, and in 2004 (not even 15 years later) Poland joined the EU.

Lech Wałęsa, on June 16, 1983, in front of the Lenin shipyard in Gdańsk, where he began working as an electrician in 1967. Photo: © Jacques Langevin / AP / picturedesk.com

But Poland has been considered a problem case in the EU since at least 2015 when Beata Szydło and her Law and Justice (PiS) party took control. This is because the leader of the PiS party, Jarosław Kaczyński, like his buddy Viktor Orbán in Hungary, is gradually undermining democratic institutions, weakening the independence of the courts and scorning all critics as enemies of the people. He, of all people, should know better. After all, Jarosław Kaczyński was once a member of the Solidarność opposition, like his twin brother Lech, who died in the Smolensk air disaster in 2010.

The European Commission recently criticised the Polish government for wanting to move forward with the parliamentary election planned for 10 May 2020 in spite of the coronavirus crisis and serious health concerns and against the will of the opposition.

It’s a paradoxical situation, says Jerzy Kochanowski, a professor of contemporary history at the Institute of History at Warsaw University, who experienced the state of emergency in 1981 as a 21-year-old history student. “Things have taken a 180-degree turn since the eighties. The PiS has ruled out the possibility of declaring a true state of emergency because that would mean postponing the election. The PiS is afraid that it will lose six months later because there will be such a big economic crisis then. The people I know are against holding the election. We are more inclined to call for a boycott to show them that we’re not planning to take part.”

An election boycott like that – if a significant percentage of voters do in fact follow through with it, as the opposition hopes – could become a problem for the PiS government, which appears to be firmly in the saddle right now. Because the state of emergency in 1981–83 was not the only time that the Polish people showed that they have limited patience for authoritarian rule.

Or, as Danuta Stołecka puts it: “Did I think Solidarność had a realistic chance in 1981? I was feeling more and more hopeless. But I wanted to do what I thought was right – with good people, people who I really liked a lot. Not because we had a realistic chance of success. But to be sand in the gears.” •

Original in German. Published in May 2020 in DATUM.

Translation into English by Douglas Fox

This text is protected by copyright: © DATUM / Julia Vitouch. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures are noted directly at the illustrations.

Cover picture: A photo from a series that was illegally distributed at the time, documenting Polish police operations between 1981 and supposably 1982. Public domain photo.