Montenegro is heading inexorably in the same demographic direction as its neighbours — and that spells bad news.

Montenegrins have long been fascinated with demographics. For decades, they have obsessed over percentages of those who consider themselves Montenegrins as opposed to Serbs, how many Albanians live in the country and whether Muslims are a distinct category from Bosniaks.

In the meantime, they are getting older, having ever fewer children and emigrating. Whether they realise it or not, how Montenegrins deal with these problems is going to determine their future, just as ethnic issues have in the past.

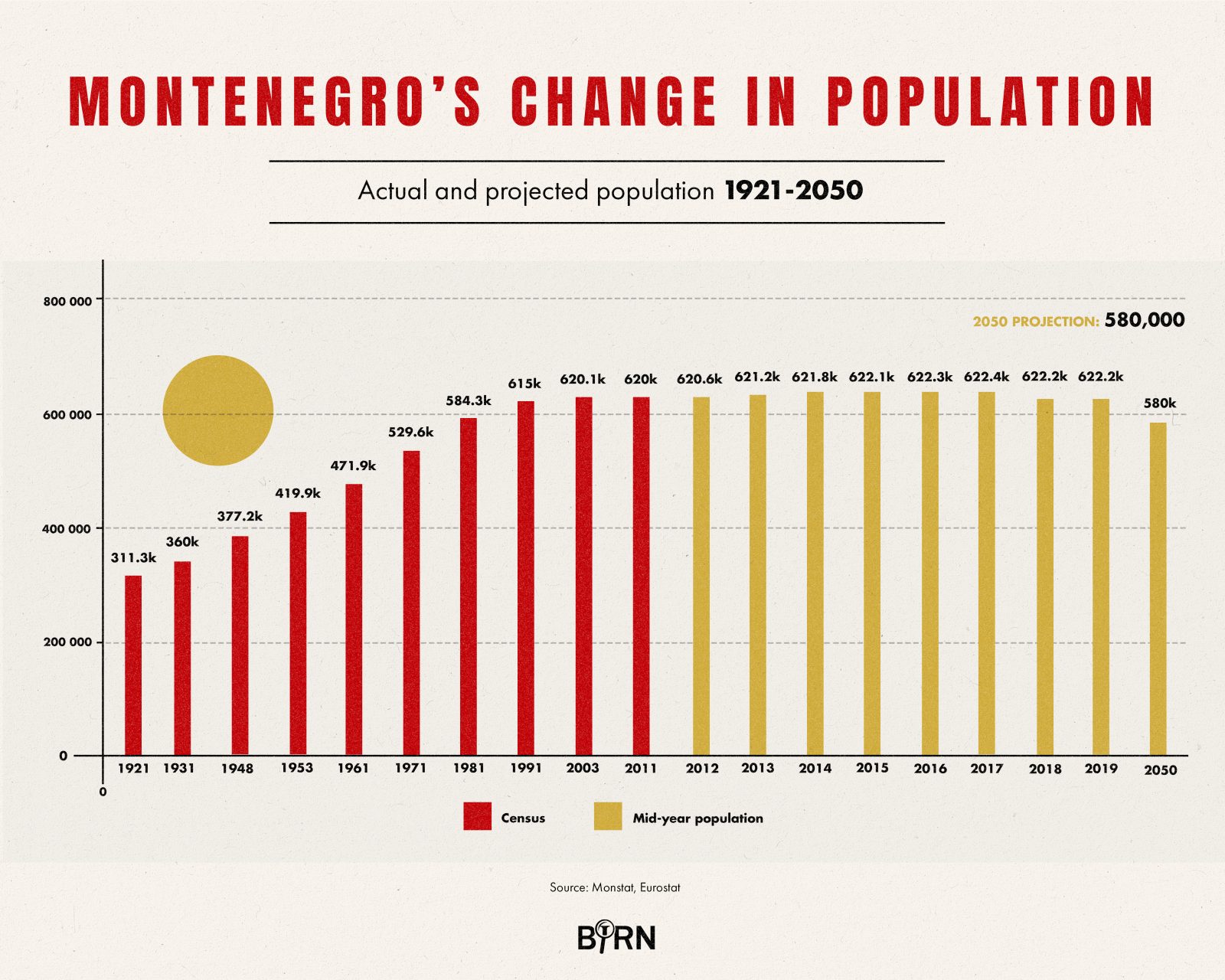

At first glance, the headline figures for Montenegro give the impression that, in a region of dire demographics, it has escaped the worst. While population numbers in all of its neighbours have been declining for years, Montenegro has bucked the trend. At the beginning of 2019, its population was estimated at just over 622,000 and that figure is virtually unchanged since 2004.

Montenegro’s change in population. Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

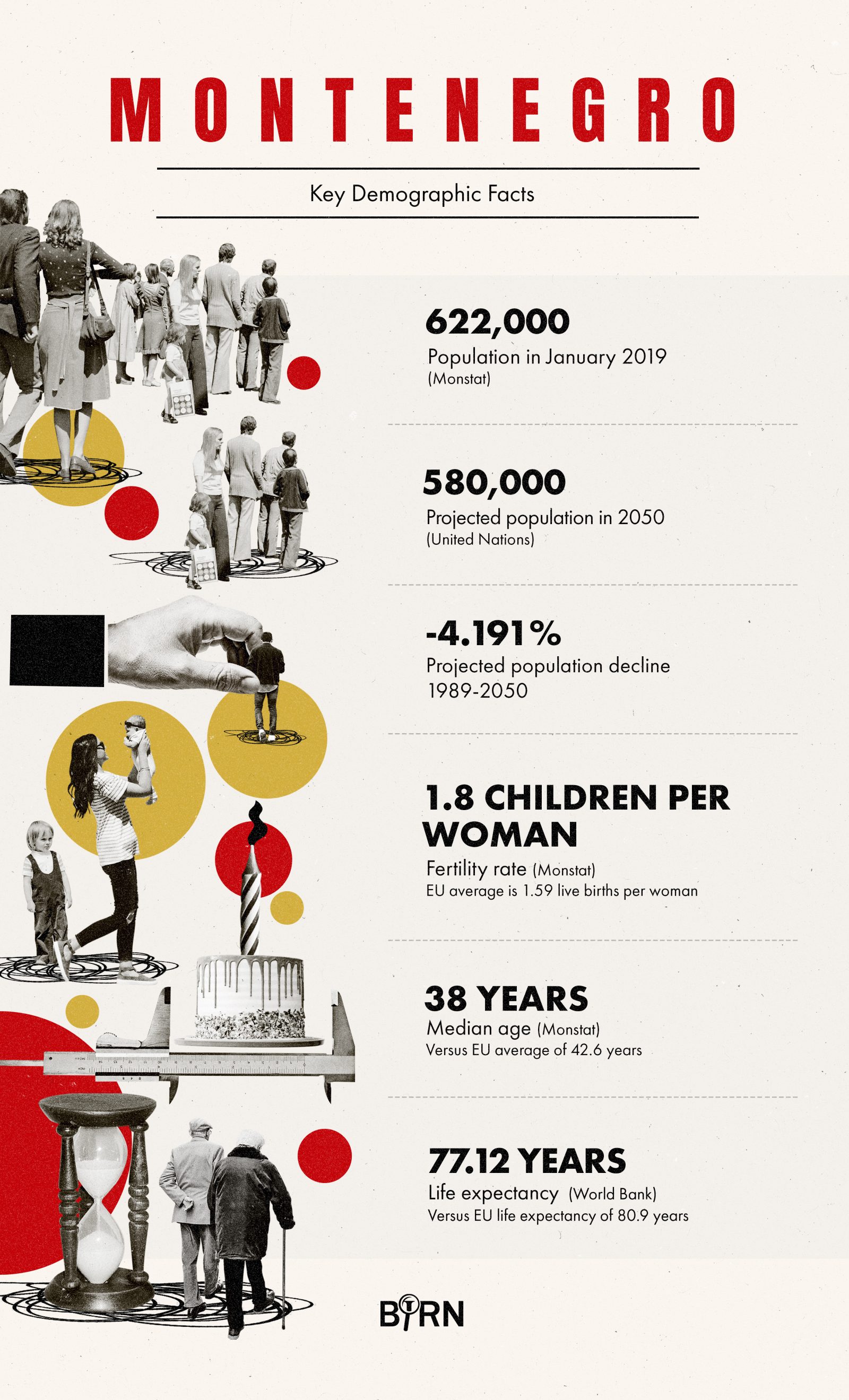

In 2018, Montenegrin women also had an average of 1.8 children, which, although below the so-called replacement level of 2.1 at which a population renews itself, is far better than anywhere else in the region bar Kosovo. It is only when you look at the trends, however, that you can see that Montenegro is heading inexorably in the same demographic direction as its neighbours.

In the 1950s, women had more than four children, a number that gently declined until the late 1980s when it began to dip below 2.1, although not every year. In Serbia, by contrast, that point was reached in 1956. In 1958, births in Montenegro exceeded deaths by 10,147, a figure that has also been declining ever since. In 2018, it was down to 760.

Miroslav Doderović, a professor at Nikšić University and the country’s only academic demographer, said he expected that the country would reach the point of “negative growth” within five years.

Montenegro. Key demographic facts. Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

The growth of Montenegro’s population from 372,000 in 1947 to the present plateau disguises the huge amount of movement and change that has afflicted the country at various periods. Between 1945 and 1947, for example, 31,000 Montenegrins were settled far from their rocky republic in the rich farmland of Vojvodina in northern Serbia, from which ethnic Germans had just been expelled. That number looks small but it was 8.5 per cent of Montenegro’s population.

Much of the Yugoslav period was one of emigration, but births outstripped the numbers leaving. In 1981, some 105,000 Montenegrins lived in other parts of Yugoslavia, 70 per cent of them in Serbia. The last Yugoslav census of 1991 recorded the republic’s population as close to 615,000 but in fact, with 23,000 working outside of Yugoslavia as gastarbeiters and their families who were included in the census totals, the actual resident number was about 592,000.

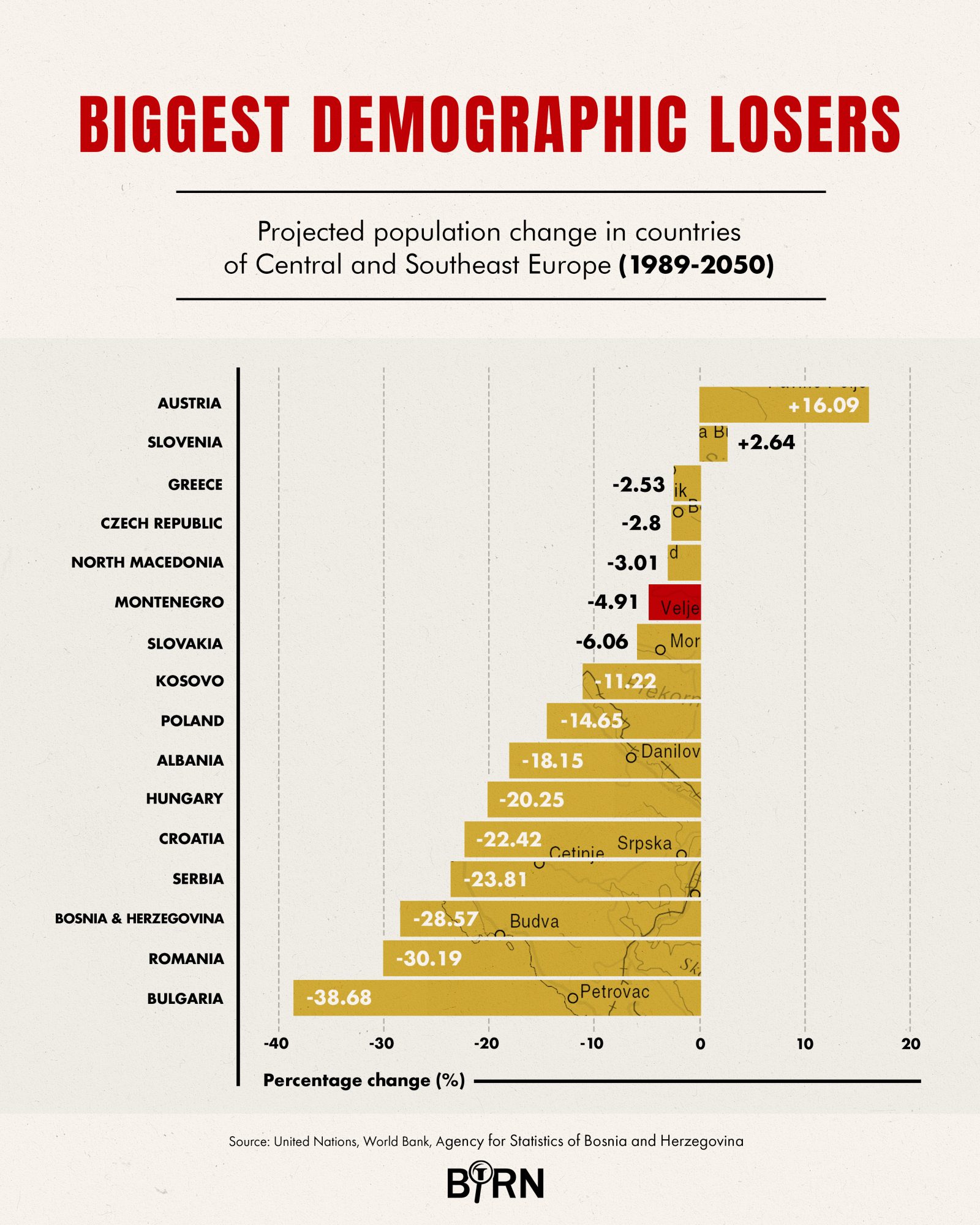

Biggest demographic losers. Projected population change in countries of Central and Southern Europe (1989-2050). Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

The turbulence of the dissolution of Yugoslavia saw huge movements of population across the country and, while there was no active conflict in the country, bar NATO bombing of selected targets in 1999, Montenegro did not escape them. It was now a country that more immigrated to than left. In the period 1990-2011, some 75,600 are recorded as coming to Montenegro and, while they may not all have stayed, the 2011 census found that 20 per cent of people in Montenegro were not born there. At the same time, people left the country but with a positive natural increase in population, the total number of inhabitants still rose before halting and staying at a constant level since 2004.

EUROPE’S FUTURES

Europe is living through its most dramatic and challenging period since World War II. The European project is at stake and its liberal democracy is being challenged from both inside and outside. There is an urgent need from all quarters of state and non-state actors to address the burning problems, both to buttress what has been painstakingly achieved through the political peace project.

From 2018 to 2021, each year six to eight leading European experts are taking up engagement as Europe’s Futures fellows. They create a platform of voices presenting ideas for action whose goal is to reinforce and project forward a vision and reality of Europe. Europe’s Futures is an endeavour based on in-depth research, concrete policy proposals, and encounters with state and civil society actors, public opinion and media.

Today’s total population figure also does not include anywhere up to 50,000 foreigners who are not permanent residents but live and work in the country depending on the season and may or nor be registered. However, permanent residents are included in the census and in 2011 they accounted for five per cent of the population, of whom four out of five came from Serbia, Bosnia or Croatia. In October 2019, there were almost 32,300 permanent residents registered in the country.

The problem Montenegro now faces is that the breakdown of its inhabitants shows that not only is the birth rate falling but that people are ageing. In 2000, the proportion of Montenegrins aged 60 and above was 17.04 per cent but now it is 21.69 per cent and that trend will only accelerate as fewer and fewer children are born and the natural increase in population turns into a decrease. In 2008, there were 121,916 children enrolled in school but a decade later that number was 98,238, or 19.4 per cent fewer. Today, Montenegro’s pension system is already under pressure and this is only set to get worse.

Arguments have raged for years about retirement ages and a policy that gave women the right to retire if they had three children, regardless of how long they had worked, was swiftly abolished because it proved so expensive. In Serbia, there will be more pensioners than people of working age in 2021 and Doderović said Montenegro would soon be the same.

However, it will not be because there are not enough people of working age but, at least in part, because governments find it is cheaper to retire workers early from the country’s bloated civil service rather than continue to pay them full salaries. In Serbia and Croatia, thousands of former gastarbeiter return every year because their foreign pensions go much further at home than in Germany or elsewhere but the numbers returning to Montenegro are negligible, said Doderović.

By contrast, the bulk of Montenegrins who went to live and work in Serbia tend not to return to live in Montenegro, rather than just come for their holidays, because the countries are so closely entwined anyway and the cost of living is more expensive than Serbia. Demographic developments are moving at different speeds in different parts of the country.

Demographic developments are moving at different speeds in different parts of the country.

For years, the poorer north has seen higher rates of emigration, both abroad but also within the country to Podgorica and the more prosperous coast, and this is leading to increasing depopulation of the north. Rožaje, for example, which is overwhelmingly Bosniak, has a comparatively high birth rate but also a high rate of emigration. For several years, large numbers, especially from places like Rožaje, tried to get asylum in EU countries, even though they had virtually no chance of success. In 2015, some 4,000 Montenegrins applied for asylum in the EU, of which 3,635 applied in Germany.

Milo Đukanović, Montenegro’s president, says that the answer lies in accelerated economic development, giving people a Western standard of living. During Yugoslav times, it used to be said that whatever the weather was up north it would soon roll down to the rest of the country. The same is true in terms of demographics. Although Montenegro appears to have escaped the worst in terms of ageing and demographic decline, that is not the case. Where Serbia and Croatia have taken the lead, Montenegro is now following, although with some decades delay.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN or ERSTE Foundation.

First published on 5 December 2019 on Reportingdemocracy.org a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The article was produced within the framework of the Europe’s Futures project.

This text is protected by copyright: © Tim Judah. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures and graphics are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy