Historically and socially, Albania is often the outlier in the Balkans. Until the fall of communism, that was the case in terms of demography too. But ever since, all the data has pointed inexorably in the same direction: Albanians are ageing, emigrating and having fewer children, just like people in the rest of the region.

“We are worried,” said Majlinda Nesturi, the director of social statistics at INSTAT, the country’s statistical agency. Nesturi has every reason to be worried. In 1958, Albanian women had an average of 6.5 children so the population exploded. Clearly no one wants to go back to that, but the last time Albania’s fertility rate was above the 2.1 level needed to replace the current population was in 2003.

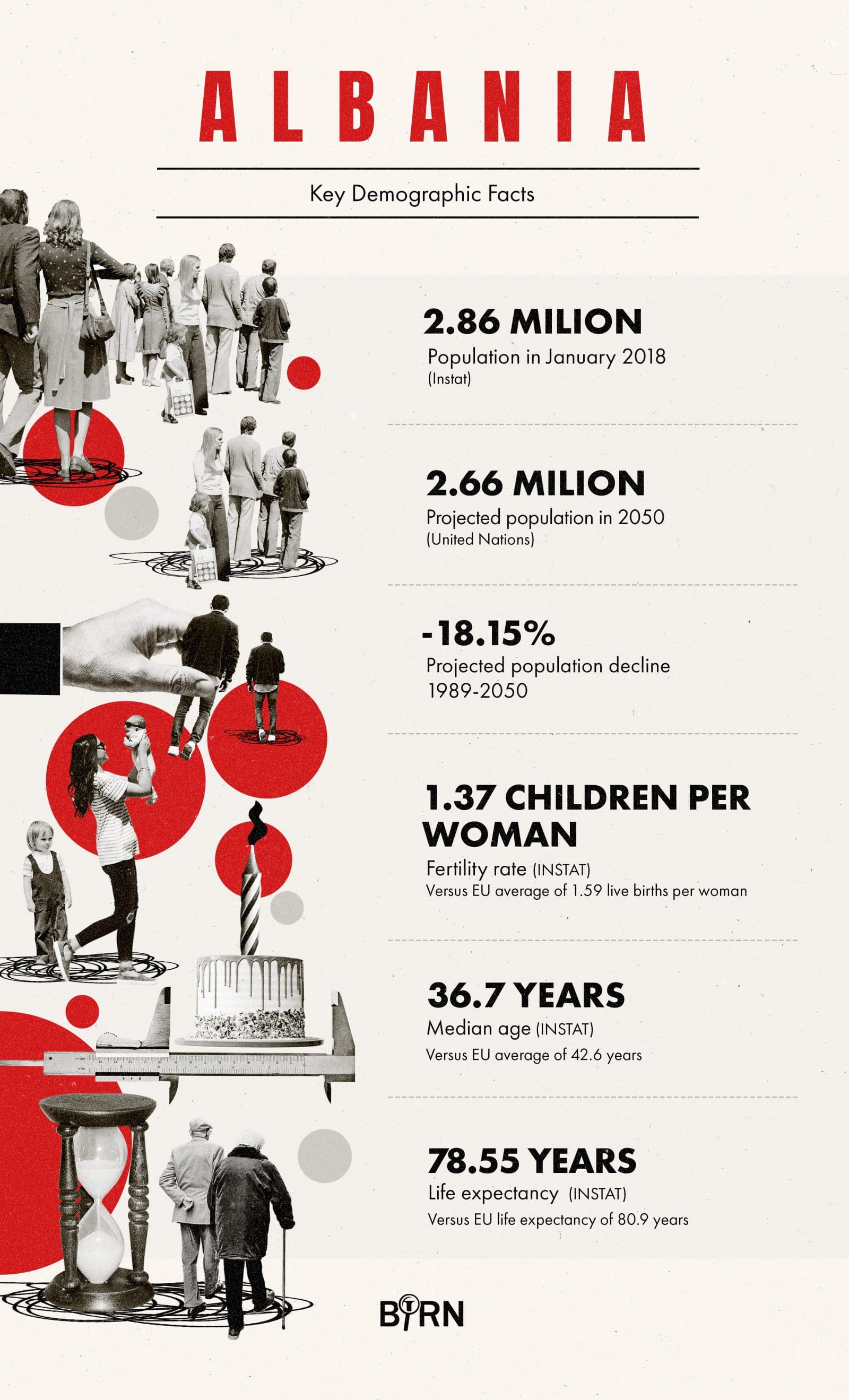

In 2018, it was 1.37, which Nesturi noted was “the lowest rate in history”. In 1990, just as communism was collapsing, there were 82,125 births in the country and 18,193 deaths. In 2018, there were only 28,934 births but 21,804 deaths, so the balance, unlike in much of the rest of the region, is still positive. But the trend is radically down, and the median age of Albanians is rising. In nine years, it has increased by more than four years from 32.6 in 2011 to 36.7 in 2019.

Albania Key Demographic Facts. Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

In a bid to encourage women to have children, families get a one-off payment of 300 euros on the birth of the first child, 600 euros for the second and 900 euros for the third. Before the collapse of communism, while Albania had a birth rate not dissimilar to that of Kosovo Albanians or Montenegrins, in terms of emigration it was utterly different from the neighbours.

Greeks had long emigrated to escape poverty and from the 1960s hundreds of thousands of Yugoslavs, including Kosovo Albanians, went to Germany and other countries as so-called gastarbeiters. Albanians, however, were completely sealed in by dictator Enver Hoxha’s paranoid regime. The contrast between the period that ended in 1991 and today could not be more stark.

Daut Dauti, a Kosovo Albanian journalist, came to London in 1985. Feeling lonely, he used the telephone book to find other Albanians. He recalls finding that there were 10 from Albania, exiles from the pre-war King Zog period, and two Kosovo Albanians. INSTAT figures, derived from the country’s civil registry, put the number of Albanian citizens abroad today at 1.64 million.

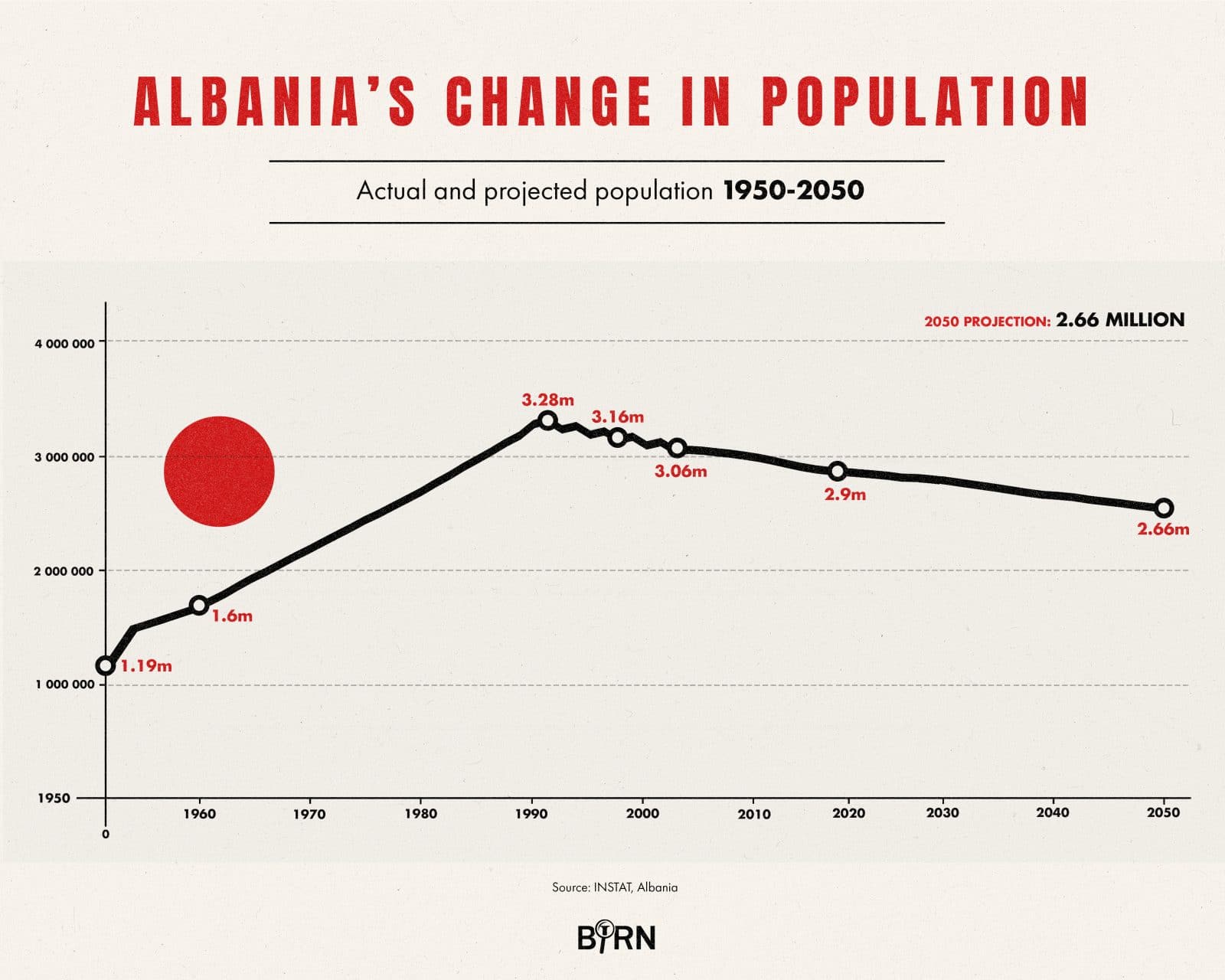

Albania’s change in population. Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

For a country that has not seen a war, that is a huge diaspora to have been created in such a short time. With so many abroad and with falling birth rates, it is not surprising that the resident population of the country, which was 2.86 million at the beginning of 2019, is dropping too. In 1991, it was 3.29 million. According to INSTAT, there are 9.7 per cent fewer people in Albania than at the time of the 1989 census.

In 1945, the census recorded Albania’s population as 1.07 million, so it tripled under communism but it has been steadily declining ever since the end of communism in Albania. INSTAT expects that by 2031, the population will be 2.75 million and a UN projection foresees it to shrink to 2.66 million by 2050.

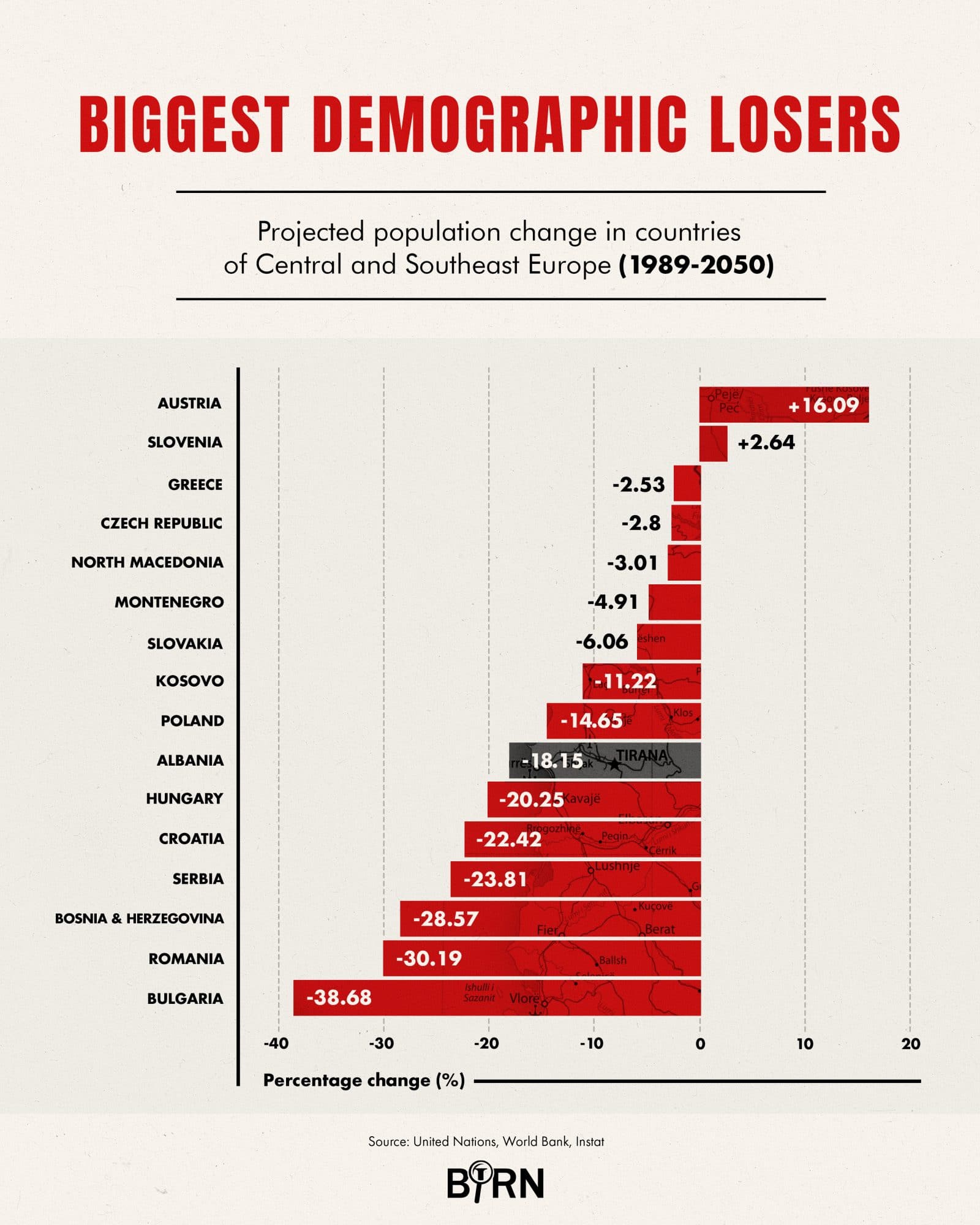

Biggest demographic losers. Illustration: © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

The question of emigration is a highly politicised and contested one. Albania’s opposition says that more than half a million people have left the country in the past decade or so alone. And indeed, if you add up the number of emigrants estimated by INSTAT over the 12 years up to 2018, you get more than that. However, INSTAT also records estimates of people coming back to the country, which come to more than 260,000 over the same period.

EUROPE’S FUTURES

Europe is living through its most dramatic and challenging period since World War II. The European project is at stake and its liberal democracy is being challenged from both inside and outside. There is an urgent need from all quarters of state and non-state actors to address the burning problems, both to buttress what has been painstakingly achieved through the political peace project.

From 2018 to 2021, each year six to eight leading European experts are taking up engagement as Europe’s Futures fellows. They create a platform of voices presenting ideas for action whose goal is to reinforce and project forward a vision and reality of Europe. Europe’s Futures is an endeavour based on in-depth research, concrete policy proposals, and encounters with state and civil society actors, public opinion and media.

It is also important to factor in that the same person can be counted several times if they come and go, which many do.

Clearly, the trend is one of net emigration but determining exact figures is almost impossible.

Circular migration, that is to say people going abroad for work for short periods, is something “we cannot measure”, said Nesturi.

One problem with trying to determine levels of Albanian emigration is that significant numbers try their luck by applying for political asylum and these numbers are not included on INSTAT emigration data unless a person regularises their status.

Almost no Albanians qualify for political asylum abroad but for many, especially from poor areas, it was and is worth applying and then spending several months in a rich EU country, housed by them, with access to social security and so on, rather than being unemployed or poorly paid at home.

Before Albanians had access to visa-free travel to the Schengen zone beginning in December 2010, the numbers trying this were small — 1,965 in all EU countries in 2010.

However, afterwards the numbers began to climb until they peaked at 68,950 in 2015, the largest number being in Germany.

In 2018, the number of Albanians applying for asylum in the EU had dropped to 22,475 but 9,665 of them, the largest single number, were in France where the system for processing people and deporting failed asylum seekers is slow, unlike in Germany.

While the number of emigrants is hard to calculate with real accuracy, Eurostat records that in 2017 some 869,455 Albanian citizens lived in the EU. Of them, 429,966 lived in Italy and 383,371 in Greece, meaning that comparatively few live elsewhere.

Since the Eurostat total is half the number of the Albanian diaspora as estimated by INSTAT, there is clearly some discrepancy somewhere, even if we allow for those Albanians who are in the US and other non-EU countries and those within the EU who are no longer counted as Albanians because they have acquired an EU citizenship. Indeed, between 2012 and 2017, Eurostat records that 286,677 did just that, the overwhelming majority of them in Greece and Italy which, apart from people leaving for economic reasons, accounts for at least some part of their declining numbers in those countries.

In Italy, the number of those registered as Albanians has dropped significantly in recent years but in Greece far less so. While Albania’s shrinking population is clearly of concern, remittances from the diaspora are a major part of the economy.

While Albania’s shrinking population is clearly of concern, remittances from the diaspora are a major part of the economy.

However, as diaspora families have to spend more on looking after themselves abroad, the percentage contribution to gross domestic product of this money has been declining over the years. According to the World Bank, in 1993 when almost nothing was working in Albania and following a first exodus of tens of thousands of young men, as much as 28 per cent of GDP was accounted for by remittances. In 2018, it was 9.6 per cent.

Another area of concern with regard to social and demographic development is the fact that not only have large numbers emigrated but they have also moved within Albania. So, while large numbers in the south have headed to Greece and large numbers from the north to Italy, large numbers from all over Albania have headed to Tirana, leading to increasing depopulation of especially rural and mountainous parts.

In the period 2019-31, the capital is projected to be the only area of the country whose population will increase, so that it will be home to about 35 per cent of the country’s population. In terms of fertility rates and ageing, Albania is not only similar to much of the rest of the region but to other parts of Europe too. However, richer countries, unlike the poorer Balkans, have immigration to make up for what would otherwise be declining populations.

But Albania’s population is still comparatively young and the number of its elderly relatively low, and this is a “demographic dividend”, according to Nesturi. It is one that will only last for a few years, though, or at most a generation, compared with Western Europe where it lasted half a century. The country needs to take full advantage of this, she said, meaning that the government must make sure that “appropriate economic and social policies are in place to provide these people with productive jobs”. Otherwise they are going to leave.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN or ERSTE Foundation.

First published on 14 November 2019 on Reportingdemocracy.org a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The article was produced within the framework of the Europe’s Futures project.

This text is protected by copyright: © Tim Judah. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures and graphics are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Illustration © Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy