Governments in the Balkans are chipping away at transparency laws to make it harder for journalists and activists to hold power to account.

Vuk Janković first got hooked when he was a law student at the University of Montenegro in Podgorica. But instead of tobacco, booze or narcotics, his addiction involves pestering state institutions for information. The best part is — they are legally required to answer him. Under right-to-know legislation introduced in Montenegro in 2005, public bodies have 15 days to respond to demands for data or documents on everything from budget spending and government tenders to the management of public property and the machinations behind privatisations.

Anyone can do it, though aficionados say crafting a killer request is an exercise in precision. Make it too vague, and institutions will dodge the question or clog up your inbox with useless attachments. “Access-to-information is often an extremely exhaustive and time-consuming process, especially when authorities are silent and avoid responding to requests,” Janković, an anti-corruption activist, told the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, BIRN. Welcome to the world of FOIA.

Right-to-know champions use the acronym to refer to the Freedom of Information Act, the big gun in their arsenal for holding power to account. They even employ it as a verb; “to FOIA” means to send a formal request under the terms of the act. FOIA requests have put politicians in the dock. They led to the ongoing trials of former Podgorica Mayor Miomir Mugosa and former Bar Mayor Žarko Pavićević, who both plead not guilty to charges of abuse of office. FOIA helped expose and convict Svetozar Marović, ex-president of the now-defunct unified state of Serbia and Montenegro, as the kingpin of a criminal group.

In law school, Janković FOIA’d courts for data for his thesis on the legalities of loan-sharking, honing skills that would serve him well in his current job as head of legal programmes at the Network for Affirmation of the NGO Sector, a non-profit commonly known as MANS. If Janković is a FOIA junkie then MANS is the perfect enabler. The organisation has a reputation for flooding institutions with information requests and refusing to take no for an answer. Janković estimates he has sent more than 50,000 FOIA forms on behalf of MANS over the past four years.

But his task is getting harder. Transparency advocates say quietly introduced revisions to the FOIA law give institutions greater discretion to turn down requests on nebulous grounds of secrecy while limiting the role of watchdogs in challenging obfuscations. “If I wanted to be ironic, I’d say the recent changes to the FOIA law will allow us to see how creative officials can be in finding reasons to declare certain information secret,” said Radenko Lacmanović, a member of the governing council of the Agency for Personal Data Protection and Free Access to Information, AZLP, the body that enforces the law.

Journalists also decry what they see as bigger barriers to scrutiny. “After the changes, everything can be classified,” said Milka Tadic-Mijovic, editor-in-chief of the Montenegrin Centre for Investigative Journalism. Backpedalling on access-to-information is not unique to Montenegro. Reporters and anti-corruption activists say institutions in neighbouring Serbia and Croatia are also undermining commitments made to match EU standards.

The result is yet another blow to independent media and civil society in countries where EU aspirations jar with stifling authoritarianism, cronyism and cultures of secrecy, they say. “Some serious limitations [in transparency legislation] have a particularly negative impact on the ability of civic actors to fulfil their role as public watchdogs,” Helen Darbishire, executive director of Madrid-based rights group Access Info Europe, told BIRN in an email. “Those limitations run directly counter to international human rights standards and the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights.”

FOIA fanatic: Vuk Janković, head of legal programmes at the Network for Affirmation of the NGO Sector, estimates he has sent more than 50,000 information requests. Photo: © Vladimir Vučinić

Unofficial secrets

On 27 April 2017, lawmakers approved new legislation to make Montenegro compliant with an EU directive on the reuse of public sector information. As an EU candidate country, Montenegro is obligated to bring its laws into line with those of the bloc. Almost as an afterthought and with no debate, they voted 42-0 in favour of four amendments to the FOIA law that members of a parliamentary committee had decided to put forward during a 10-minute meeting earlier that afternoon, according to minutes of that meeting. The decision by the Committee on Political System, Judiciary and Administration came just three days after a ruling party lawmaker named Marta Scepanovic had told the committee that changes to the FOIA law were needed to “make it more efficient”, the minutes said.

No members of the opposition took part in the vote. At the time, they were boycotting parliament over allegations of electoral abuse by the governing Democratic Party of Socialists, perennial rulers since Montenegro introduced multi-party politics in 1990. Scepanovic declined an interview request and did not respond to emailed questions about why she felt the law needed changing. Zeljko Aprcovic, president of the committee, also declined an interview request. But while the EU directive encourages countries to make as much public information available for reuse as possible, transparency experts say the amendments help lock it away.

“After the changes, everything can be classified”

Analysis of the changes by Access Info Europe and MANS highlighted a “series of general, broad, and vague exclusions” that give authorities enormous discretion to classify information and turn down FOIA requests. These include exclusions related to business and tax secrets as well as information about parties in judicial proceedings. Fuzziest of all is an exclusion that refers simply to “information that must be kept secret”, with no clear definition of what that might mean. “The rather remarkable concept of ‘information that must be kept secret’ risks undermining the whole Law on Free Access to Information and makes a mockery of other provisions of the law, of the Montenegrin constitutional provision on access to information, and of the international standards that Montenegro is bound to uphold,” the analysis said.

In a working paper written in November 2018, the Council of the European Union called for a “thorough revision of the legal framework in accordance with international standards”. “The implementation of the law on free access to information has not contributed to ensuring more transparency and accountability of public service, as the authorities continue declaring requested information as classified, including on subject-matters sensitive to corruption, thus excluding it from the scope of application of this law,” it said.

A FOIA request form. Photo: © Vladimir Vucinic

Since the changes, cases of institutions evoking secrets to deny access to information have shot up. According to the European Commission’s 2017 report on Montenegro, secrecy was cited in 68 denied requests, compared with 30 the year before and 104 denied requests a year later, in 2018. That is more than double. “It is a cause for concern that more and more requested documents are declared secret in order to limit the access to information,” the report said.

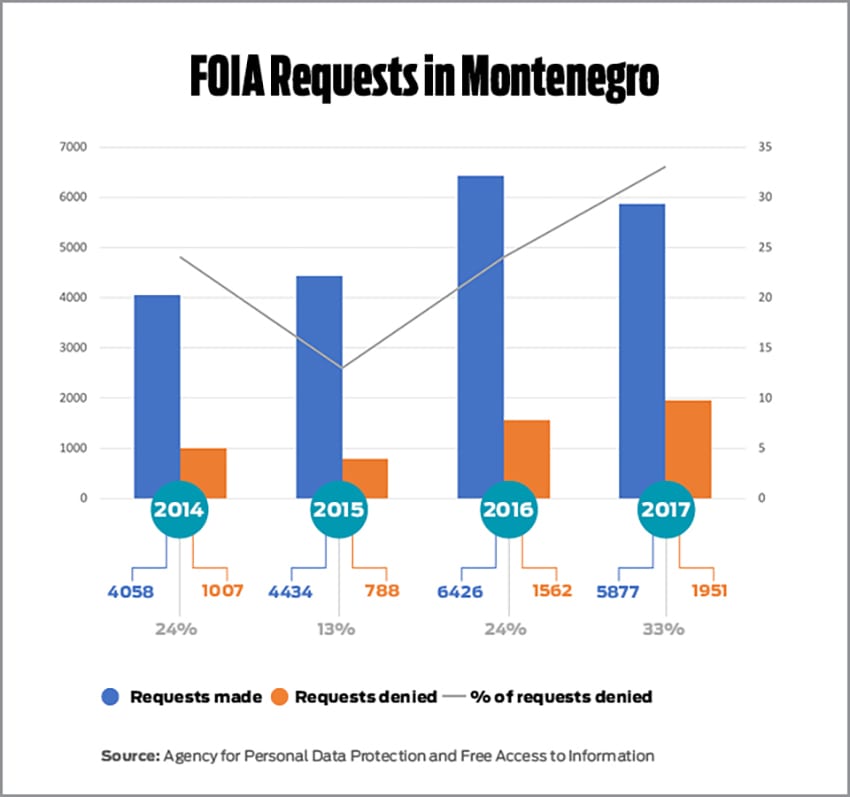

The EU Delegation in Podgorica also condemned the trend. “We call on public institutions to urgently improve the implementation of the law and comply promptly with access-to-information requests in accordance with the principles of transparency and good governance, especially in areas where there is a risk of corruption,” the delegation told BIRN in an email. Meanwhile, the overall number of information requests rejected by public bodies is rising steadily. 2017, institutions rebuffed 33 per cent of all requests, compared with 24 per cent in 2016 and 13 per cent the previous year, according to data from the FOIA agency.

Those numbers dwarf denials in other countries. Across the border in Croatia, an EU country with right-to-know legislation on its books since 2003, authorities turned down around five per cent of requests in 2017 and three per cent a year earlier, Information Commissioner data showed. Experts say authorities and public companies rarely bother to explain the criteria they use to classify data, making the FOIA process feel at times Kafkaesque. In June 2018, BIRN sent a FOIA request to the state-owned Investment Development Fund of Montenegro asking for a copy of internal regulations used to declare documents confidential. The fund’s reply: the regulations are themselves confidential (see box).

Just say no

For more than a year, the investigative department of public broadcaster RTCG was probing the use of millions of euros of loans for agricultural projects in Montenegro from the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development. Since taxpayers will foot the bill if the loans are not repaid, journalists see the story as a matter of public interest. “We’ve sent dozens of requests [to various institutions] … asking for the same thing,” said Mirko Boskovic, editor of RTCG’s investigative department. “Before the amendments, we could get some information, but after the law was changed they found every possible and impossible reason to reject us.”

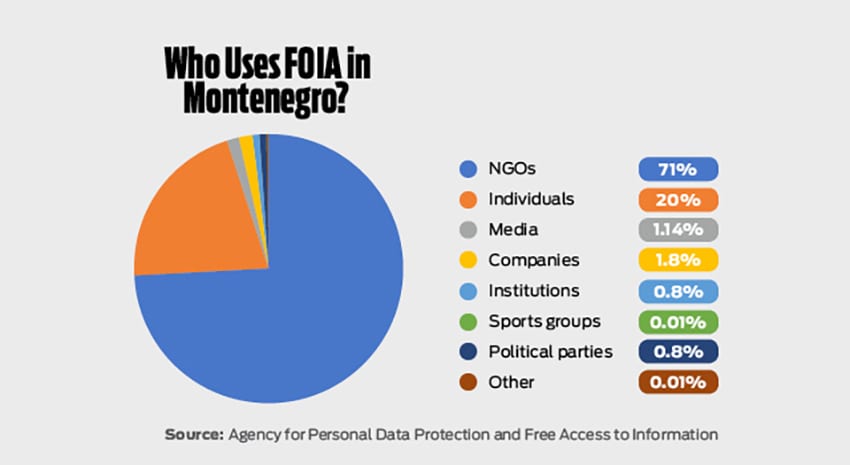

While the FOIA amendments have made life harder for journalists, they are likely to have the biggest impact on NGOs — if only because NGOs are the main users of the law. In 2017, 71 per cent of all FOIA requests in Montenegro came from NGOs, compared with 20 per cent from individuals and just over one percent from media, according to agency statistics.

Chances are, a good chunk of those came from the famously prolific MANS. Some say MANS goes too far, overwhelming public servants with pointless paperwork in its crusade for accountability. But even critics concede it has the art of writing FOIA requests down to a science. MANS makes a point of contesting every FOIA request ignored or rebuffed by institutions, first appealing the decisions to the AZLP. Those appeals end up on a desk at the AZLP’s headquarters in central Podgorica, where Muhamed Gjokaj, chairman of the agency’s governing council, laments the workload for his team of a dozen or so people. “All these are from MANS,” Gjokaj said with a sigh, pointing to a pile of papers as thick as a fat phone book. The pile has been steadily growing since last year’s amendments. Janković, head of MANS’ legal programmes, gave the example of Montenegrin Electric Enterprise, a majority state-owned company that he said rebuffed a request for information on how it buys and sells electricity, citing the business interests of foreign partners.

Mirko Boskovic, editor of broadcaster RTCG’s investigative department. Photo: © Vladimir Vucinic

Business secrets also got in the way of MANS’ inquiries into the reconstruction of the Pljevlja Power Plant, Montenegro’s only thermal power station. “They disregarded the fact that the key interest to be protected by a company whose majority stakeholder is the state, is the public interest itself,” Janković said. FOIA seekers can dispute such decisions at the Administrative Court. Asked how the court can decide on hazy matters of secrecy without clear definitions, a court spokeswoman said rulings were made on a case-by-case basis. “As to whether the amendments leave a wide space for free interpretation, that is for those who proposed them to say,” she told BIRN in an email.

Another change that worries transparency activists is the removal of a legal requirement for the AZLP to adjudicate on appeals against rebuffed requests — the kind of work done by Gjokaj and his team. In the past, the AZLP could overrule refusals and force institutions to disclose information. Under the revised law, the agency can still intervene but it is purely optional. “If one may do something but has no obligation to do so, it means that in most cases it won’t be done,” said the agency’s Lacmanović.

But Gjokaj welcomed the change, saying the AZLP had been swamped by appeals, all of which had to be decided in 15 days. He added that some people had tried to abuse the system by submitting vast numbers of FOIA requests in the hope of pocketing payouts for court expenses when officials inevitably failed to process them all. “For example, someone asked [a school] for its decision on the use of a gym, on the first day, on the fifth day, on the 15th day of the month, and eventually you have 150 requests for the single case,” he said. “Then a colleague repeats it all. So you have 300 requests. Is that information of relevance to the public?”

The exterior of the Agency for Personal Data Protection and Free Access to Information in Podgorica. Photo: © Vladimir Vucinic

Cultures of secrecy

On paper at least, Serbia and Croatia put Montenegro to shame when it comes to right-to-know legislation. In fact, Serbia’s Law on Free Access to Information of Public Importance is often cited as a gold standard. According to a global ranking of such laws by Access Info Europe and the US Centre for Law and Democracy, it is third-best in the world, after Afghanistan’s and Mexico’s. Croatia’s equivalent law is ranked eighth. Montenegro’s is 59th.

Putting FOIA to the Test

To put Montenegro’s revised Freedom of Information Act to the test, BIRN sent formal requests for information to public bodies between June and August 2018. For comparison, we sent similar requests to relevant institutions in neighbouring Serbia and/or Croatia. Here is a brief summary of the results.

Electricity

We asked public utilities in Montenegro and Serbia for contracts with foreign companies that are rebuilding power plants.

- Montenegro

What we wanted: Contracts with a consortium of companies from Italy and Slovenia rebuilding and modernising the Piva Hydroelectric Power Plant

How Montenegrin Electric Enterprise JSC answered: No reply - Serbia

What we wanted: Contracts with Russian company Silovije Masini, which is rebuilding the Iron Gate I Hydroelectric Power Station

How Public Enterprise Electric Power Industry of Serbia answered: Request denied. The documents are classified due to national security and business secrets.

t

t

Development funds

We asked publically run development funds in Montenegro, Croatia and Serbia for their internal regulations on criteria used for classifying information as secret.

- Montenegro

What we wanted: The Investment Development Fund of Montenegro’s internal regulations on classifying information

How they answered: Those regulations are themselves classified. - Croatia

What we wanted: The Croatia Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s internal regulations on classifying information

How they answered: Request denied. We complained to the Commissioner for Information, which upheld our complaint and ordered the bank to send us the information and publish the internal regulation on its website. - Serbia

What we wanted: The Fund for Development of Serbia’s internal regulations on classifying information

How they answered: No reply

t

t

t

Railways

We asked national rail companies in Montenegro and Serbia for a range of documents related to the purchase of new trains.

- Montenegro

What we wanted: Tender applications and contracts on new train purchases held by Railway Transport of Montenegro JSC

How they answered: No reply - Serbia

What we wanted: Tender applications and contracts on new train purchases held by JSC Serbian Railways

How they answered: We don’t have it. Ask Joint Stock Company for Passenger Railway Transport, Srbija Voz. We did, and they said: ask JSC Serbian Railways.

t

t

Roads

We asked the transport ministry in Montenegro and public company Koridori Srbije in Serbia for contracts with Chinese companies building highways in both countries.

- Montenegro

What we wanted: Contracts with China Road and Bridge Corporation, CRBC, and subcontractors

How the transport ministry answered: Two months after our request, the ministry allowed us to see the contract with CRBC but declined to provide documents related to subcontractors on the grounds that CRBC is the main contractor. - Serbia

What we wanted: Contracts with two Chinese companies, China Communications Construction Company and Shandong Hi-Speed Group

How Koridori Srbije answered: Ask Public Enterprise Roads of Serbia, another public company. We did, and they did not reply.

t

t

Photo: © Vladimir Vucinic

In 2015, Serbian reporters working for the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, a non-profit investigative journalism network, used the legislation to reveal that then Belgrade Mayor Sinisa Mali was director of a $6 million property empire on the Bulgarian Black Sea. In 2017, the law helped the Crime and Corruption Reporting Network, another investigative journalism group, look into the questionable property dealings of Serbian Defence Minister Aleksandar Vulin. But transparency champions say even the finest legislation is only as good as its implementation.

In Serbia, state institutions and public companies simply ignore many of the 30,000-plus requests logged each year by the Commissioner for Information of Public Importance and Personal Data Protection, journalists say. “More and more institutions are closed to the public, refusing to communicate with journalists or to respond to our requests,” said Dino Jahić, former editor of the Center for Investigative Journalism of Serbia. “It seems to me that all this is the consequence of a public climate in which journalists have come to be seen as evil, as enemies who work to damage the state and Serbian society.”

In 2017, the Ministry of Public Administration announced plans to amend Serbia’s right-to-know law that alarmed activists in the EU candidate country. Assistant Minister Ivana Antić told BIRN the changes were designed “to improve the legislation” and bring more state bodies into the FOIA fold. But critics said amendments drafted by the ministry could effectively legalise the current culture of secrecy by letting many organisations off the hook — particularly the public companies that build roads, run railways and provide electricity, telecommunications and other services. “These are state-owned companies that do business with public resources and they could be exempted from FOIA according to the new draft,” said Mirjana Jevtovic, an editor at investigative news outlet Insajder.net. “This means that citizens will not be able to find out how their money is spent.”

Nemanja Nenadić, programme director of Transparency Serbia, described the proposed exemption for public companies as “a matter of political pressure and an intention to hide information”. Critics also worried that changes could allow state institutions to tie the system up in knots through legal action. When public bodies deny or ignore FOIA requests, people have the right to appeal to the information commissioner, which can force the institutions to release the data. An amendment drafted in March 2018 would let public bodies contest such decisions in the Administrative Court. “Someone had the ingenious idea that institutions, which mostly don’t answer requests, should be allowed to sue the commissioner for the decisions passed,” said Commissioner for Information Rodoljub Šabić, shortly before his term in office expired in late December. “This amendment would result in thousands of complaints against the commissioner. The exercise of this right, which is already very complicated and time-consuming, would be painfully extended, and in the case of journalists, become meaningless.”

In a victory for campaigners, the Ministry of Public Information released a revised draft of the legislation in December 2018 that no longer included the provision allowing institutions to sue the Commissioner for Information. But transparency advocates say they will not sleep easy until they see the final version of the legislation. Among their concerns is a new provision in the December draft determining that the National Bank of Serbia is “without justification excluded from the competence of the Commissioner”. According to analysis published by Transparency Serbia, the December draft also missed an opportunity to safeguard the independence of the Commissioner for Information. Under the current law, commissioners are elected by deputies in parliament, a process that critics say is open to political interference. Serbia has been without a commissioner since Šabić — who had a reputation for independence — left office in December. Aleksandar Martinovic, the ruling Serbian Progressive Party’s leader in parliament, said at the end of January the party had several candidates for the job — and that whoever they put up would be “the exact opposite” of Šabić.

Meanwhile, journalists and transparency activists have been on the offensive. A campaign called Serbia for Information (in Serbian), organised in the run-up to Christmas by Belgrade-based NGO the Centre for Research, Transparency and Accountability (CRTA), sought to raise awareness of the changes by allowing people to “ask Santa” for public information. “We all know that Santa’s job is to bring presents to us,” the NGO said on its website. “However, if such a draft law is adopted, it may be necessary, instead of a gift, to provide us with answers to questions about how our money is spent.” CRTA has also launched a campaign called “I want a commissioner, not a yes-man!”, calling for the transparent election of the next Commissioner for Information. A form on the group’s website allows members of the public to propose to parliament their own criteria for the next appointee.

Across the border in Croatia, requests for data in the EU’s youngest member state often hit a wall of classified information and trade secrets. The number of FOIA requests denied by public bodies almost doubled in 2017 compared with the previous year, accounting for around five per cent of almost 22,000 requests submitted, data from the Information Commissioner showed. “Business secrets is one of the most common reasons for restricting access to information,” Commissioner Ana Marija Musa told BIRN in an email. Ilko Ćimić, an investigative reporter at Index.hr, said many Croatian institutions had a special knack for fobbing off FOIAs. “Sometimes they refuse requests with no explanation at all, saying you are abusing the right of access by requesting information too often,” he said.

Back in notoriously secretive Montenegro, such complaints have a familiar ring. Janković from MANS said the payoff for all the hours of banging his head against the system was seeing crooked officials brought to justice — such as in the so-called Zavala affair in which associates of former State Union of Serbia and Montenegro President Svetozar Marović got jail time for corruption. “The process is inherently complex for an organisation like MANS, which has been dealing with this area for many years, so you can imagine what it’s like for an average citizen of Montenegro,” he said.

First published on 5 March 2019 on Balkaninsight.com.

This slightly updated text is protected by copyright: © Dušica Pavlović, edited by Timothy Large. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Files and more files. Transparency advocates say recent changes to freedom-of-information legislation in Montenegro are helping state institutions lock public information away. Photo: © Vladimir Vucinic

This article was produced as part of the Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation and Open Society Foundations in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.