Once the scourge of crooked politicians, Romania’s anti-corruption agency is besieged and battered. Many fear it will never be the same.

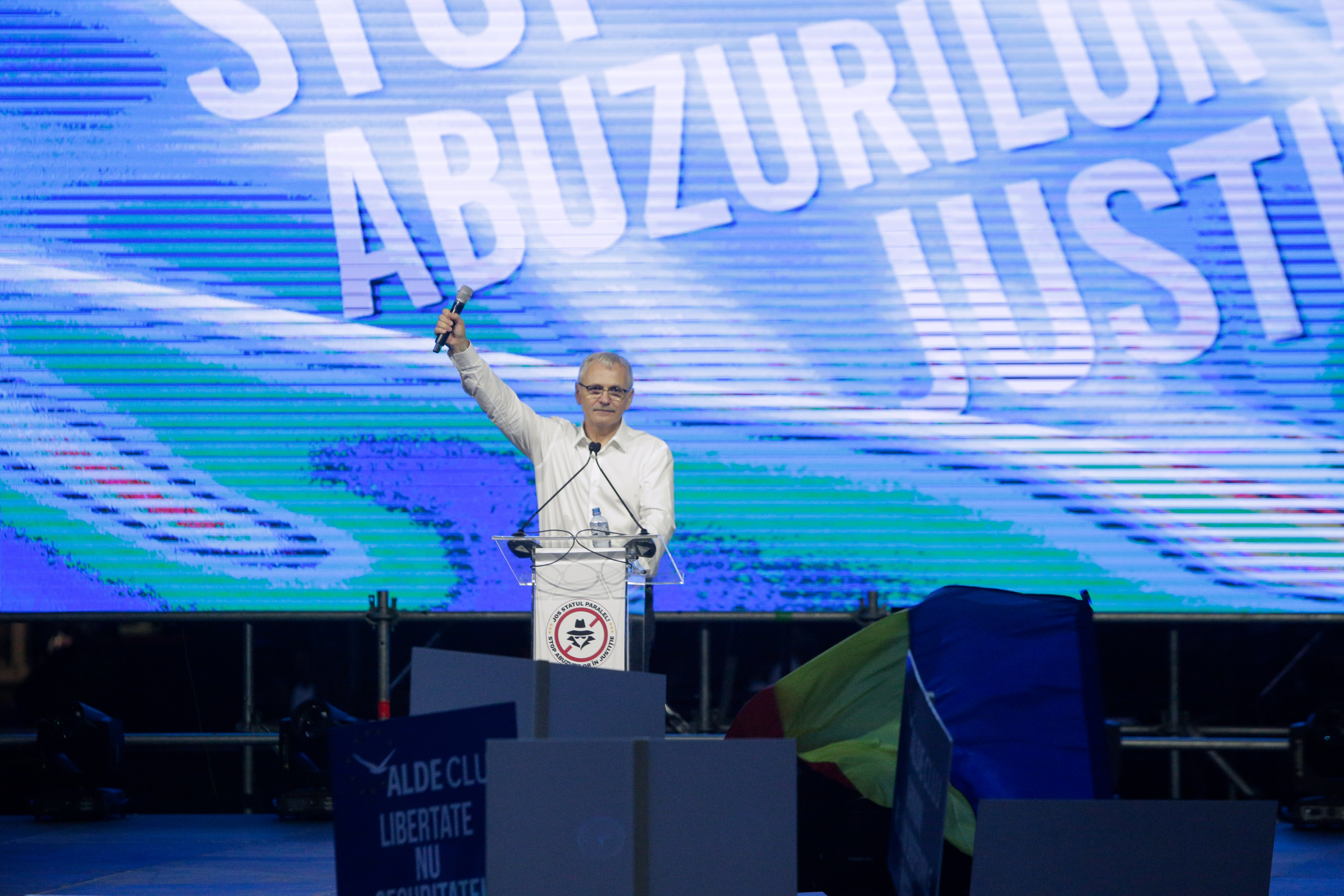

Shortly before 10 p.m. on a balmy summer evening, Liviu Dragnea strode onto the stage in Bucharest’s Victory Square as a sea of people waving Romanian flags erupted into cheers. Wearing a pressed white shirt without a tie, he put a hand on his hip and waited for the crowd to hush as the words “terror”, “insecurity”, “victim” and “fear” flashed on a giant screen behind him.

Many of the 150,000 people at the 9 June 2018 rally had been standing in front of the government building since before noon, bussed in from around the country. They had come to see the man known as the most powerful figure in Romanian politics. Dragnea, the 56-year-old leader of the ruling Social Democratic Party, PSD, began speaking with a measured tone that belied the sensationalism of his theme. Romanian democracy, he said, was under attack from a shadowy “deep state” whose “emissaries” include prosecutors, secret service agents, journalists and non-governmental organisations bankrolled by foreign cash.

“We’re being encouraged, threatened, blackmailed to inform on our relatives, our friends, our colleagues, even people we’ve never met,” he said, evoking memories of the Securitate secret police that terrorised Romanians during the country’s communist past. “It doesn’t even matter if you’re guilty or not.”

As an image of a gun’s crosshairs flashed on the jumbotron, Dragnea aimed his fire at the National Anti-Corruption Directorate, DNA. Romania’s anti-graft agency has a fabled record of putting powerful people behind bars in one of Europe’s most corrupt countries. It has become a favourite target of PSD lawmakers who accuse it of playing dirty to get convictions.

“The corrupt prosecutors are still here,” Dragnea said. “You’ve seen them on TV fabricating cases, falsifying statements. You’ve heard them threatening witnesses. The chief of the DNA is still here. You heard her asking prosecutors to bring her big heads [convict prominent politicians].” As the crowd jeered, Dragnea did not mention his own run-ins with the DNA, including a 2016 court battle that ended with a two-year suspended sentence for trying to rig a referendum. At the time of the rally, he was also on trial for abuse of office; DNA prosecutors were seeking jail time of seven-and-a-half years.

Liviu Dragnea, leader of Romania’s ruling Social Democratic Party, salutes the crowd at a rally in Bucharest in June 2018. Photo: © George Calin

Two days later, during a late-night session of parliament, lawmakers passed dozens of changes to Romania’s criminal procedure code, making it harder for prosecutors to investigate cases. The amendments were the latest in a series of sweeping justice reforms that have divided the country.

Ten days after that, Romania’s highest court found Dragnea guilty. Judges gave him three years and six months, pending appeal. They ruled that he had intervened to keep two secretaries at a local PSD branch fraudulently on the state payroll when he was a local council leader. The verdict was a victory for the DNA – but few at the agency were celebrating. Within a fortnight, its charismatic chief, Laura Codruta Kovesi, was out of a job, sacked at the behest of the justice minister after a five-year tenure that had made her a darling of the global transparency movement.

Former anti-corruption chief Laura Codruta Kovesi had a reputation as a “controversial star”. Photo: © Octav Ganea

Today, the DNA’s activities have all but stalled. Its caseload has shrivelled to a handful of minor files. It remains without a director, and insiders fear the next chief will be a toady of the government. Behind the PSD’s deep-state conspiracy theories, many analysts see a calculated effort to turn a once lionised institution into a paper tiger, toothless and vulnerable to political interference. “No one is spelling it out like that, but it appears as if the PSD wants to save its own members [from the possibility of corruption investigations],” Codru Vrabie, an anti-corruption expert and host of a podcast on the justice system, told the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, BIRN.

Others view the DNA’s decline as an inevitable consequence of a broader assault on judicial independence that has sparked unprecedented public protests and invited comparisons with illiberal regimes in Hungary and Poland. “First, you attack the justice system, so you don’t have to answer for your actions later,” said Elena Calistru, founder of transparency watchdog Funky Citizens. “Then you take advantage of your parliamentary majority to impose your legislative agenda, no matter what everyone else is shouting around you. Then you take on a nativist approach when European institutions react… And you start attacking civil society, you capture the media and that’s it.”

Great expectations

The National Anti-Corruption Directorate, DNA, is a by-product of Romania’s EU aspirations. As the country began accession talks in the early 2000s, then Prime Minister Adrian Nastase received homework from Brussels: tackle corruption in a serious way or stay outside the bloc. Nastase established the precursor to the DNA almost overnight with an emergency decree.

“This was 2002, when Romania abounded in laws and institutions that were built correctly but didn’t work in practice,” recalled Laura Stefan, director of anti-corruption policy at the Justice Ministry between 2005 and 2007. “When they built the institution, they thought it would never work. What we need to realise is the fight against corruption is not a consensual thing for politicians. They see it as a means to an end, usually in terms of EU accession.”

It was after Liberal Democrat Traian Basescu became president in 2004 that the DNA started to get teeth. Under Justice Minister Monica Macovei, a former human rights advocate, the agency was given a mandate to investigate high-level graft and the mishandling of European funds.

Meanwhile, the independence of prosecutors was strengthened through three “justice laws”, as legal experts called them. Macovei publically encouraged the DNA not to be intimidated by the powerful people it was investigating. “The DNA took off after that,” said Roxana Bratu, author of Corruption, Informality and Entrepreneurship in Romania. “It became an extremely powerful institution, with extremely powerful political support and plenty of money.”

Laura Codruta Kovesi took over as DNA chief in 2013, six years after Romania joined the European Union. Prosecutions jumped under her leadership. “An institution like the DNA showed that no one is above the law,” said Elena Calistru, founder of transparency watchdog Funky Citizens, adding that many people looked up to Kovesi as a kind of graft-busting superhero.

“Romanians, despite anything said about them, want to feel like justice is served. They look for heroes. That’s the culture we live in, and they need to see that things are moving.” After a deadly nightclub fire in Bucharest shocked the nation in 2015, many people looked to the DNA for justice. Prosecutors opened a case to see if administrative corruption was to blame but it reached no conclusions.

In January 2017, more than 500,000 people protested against the government after an emergency decree decriminalised certain types of abuse of office, chanting, “DNA should come for you!” Prosecutors opened an investigation to see if officials had been bribed to adopt the legislation but the Constitutional Court ruled that it was not the DNA’s business to investigate “political opportunity”.

“This is where civil society needs to come in and not lead people into thinking that everything can be solved with a criminal file,” Stefan said. “There’s been a lot of pressure on the DNA to try and solve every problem out there. The honest answer from them would be, ‘It’s not our job.’ But how would that be received in a society that expects everything from criminal justice?”

“I want a country without convicted criminals,” reads a placard at an anti-government protest in Bucharest in August 2018. Photo: © Octav Ganea

“Crusader”

Two hours after she was sacked on 9 July, Kovesi stood in the marble hallway at the entrance to DNA headquarters in central Bucharest, flanked by almost 40 of her prosecutors. “I have a message for Romanian citizens,” she told reporters. “Corruption can be defeated. Don’t give up.”

Kovesi’s dismissal came as no surprise. In February, Justice Minister Tudorel Toader had started a process to remove her, accusing her of overstepping her mandate and making Romania look bad abroad, among other wrongdoings. President Klaus Iohannis, a former leader of the opposition National Liberal Party and an admirer of Kovesi, at first refused to fire her. In May, the Constitutional Court decided that the president had no power to overrule the justice minister. Reluctantly, Ioannis signed her marching orders.

Kovesi, a 45-year-old former professional basketball player, had become something of a giant in the eyes of many Romanians fed up with endemic graft. Last year, only Bulgaria and Hungary fared worse among EU states in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. Since it was established in 2003 in the run-up to Romania’s EU accession of 2007, the DNA has carried out more than 43,000 investigations and prosecuted over 12,300 people, indicting 23 ministers past and present and jailing a former Prime Minister, Adrian Nastase.

“It’s something you will not find in other transitional countries like Ukraine, Moldova or Bulgaria,” said Hartmut Rank, head of the Rule of Law Programme South East Europe at the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Bucharest. “The number of cases shows that it’s been taken seriously here.”

Kovesi — who was 33 when she became Romania’s youngest prosecutor general and 40 when she took over the DNA in 2013 — oversaw some 4,000 prosecutions as head of the agency, making her tenure the most prolific of any director’s. She had a flair for the dramatic. In 2014, masked police entered a restaurant in the eastern city of Constanta to arrest former Mayor Radu Mazăre. Two years ago, officers paraded Labour Minister Lia Olguţa Vasilescu in handcuffs outside DNA headquarters, to the delight of photographers. Mazare was sentenced to six-and-a-half years in prison in May on abuse-of-office charges linked to the sale of public seaside property, though the former mayor has fled to Madagascar. Vasilescu was charged with bribe-taking and influence-peddling but judges released her and sent her file back to the DNA for further investigations. She claims the DNA is plotting to accuse her of dozens of corruption charges.

Kovesi declined to be interviewed after her dismissal, but she discussed the scope of her work in an interview with BIRN in May. “If you look at the category of people we investigated, we’ve had mayors, presidents of county councils, MPs, a variety of professional categories,” she said, sitting in her office decorated with pictures of saints and a basketball on a glass stand, a reminder of her athletic past. “We’ve had people from various parties. Until then, it was always said that the DNA only investigates a certain party. The DNA’s investigations involved almost all state institutions.”

By 2015, national opinion polls showed that Romanians trusted Kovesi more than the head of the Orthodox church — and significantly more than their elected representatives. That same year, a Flash Eurobarometer telephone survey of 300 people on businesses and corruption carried out by the European Commission suggested that while Romanians were more pessimistic than their EU peers in believing corruption was widespread, they were happier about how it was being tackled. The international press doted on Kovesi. The Economist wrote in 2016 that she was “cleaning up” Romanian politics. The Guardian called her a “crusader” against corruption. For the BBC, she was a “controversial star” who gained public trust and perhaps too much power.

“Pound the table”

Not surprisingly, Kovesi made enemies. Many rode to power in parliamentary elections in 2016 when the PSD won its first comfortable majority since 2004 as the senior partner in a coalition government. “The consequences of [the war on corruption] is you angered a lot of political and economic interests in the country,” said Mark Gitenstein, US ambassador to Romania between 2009 and 2012. “Some of the defendants have access to PR firms and lobbyists, own TV stations, and their basic goal is to try to discredit the integrity of the system.”

Gitenstein, a law graduate, continued: “We had an expression in law school: when the facts are against you, argue the law; when the law is against you, argue the facts; when they’re both against you, pound the table. That’s what the defendants are doing now.”

In early 2017, the PSD-led government began pushing controversial justice reforms through parliament, sparking massive anti-government protests and international condemnation. The government justified the reforms by saying Romania needed to align itself with EU directives on defendants’ presumption of innocence, as well as to defeat the forces of the “deep state” that is said were subverting democracy. Critics said they undermined judicial independence and threatened the rule of law.

Laura Codruta Kovesi addresses reporters shortly after being dismissed as head of the anti-corruption agency. Photo: © Octav Ganea

In January 2017, the cabinet tried to bypass parliament by passing an emergency decree that effectively decriminalised certain lower-level corruption offences. More than half a million people took to the streets in anger, forcing the government to repeal the decree. “When they saw this didn’t work, they thought, ‘Let’s take down the boss — it’s easier,’ and put their guns on Kovesi,” said podcaster Vrabie.

Directing the artillery were Dragnea and other prominent PSD lawmakers including former Justice Minister Florin Iordache, who had introduced the emergency decree that incensed Romanians, and Liviu Pleşoianu, a lawmaker in the lower house. Last year, Pleşoianu staged a protest in front of DNA headquarters, mocking “the anti-corruption temple” and demanding the dismissal of Kovesi, whom he accused of plagiarising her doctoral thesis and abusing her power.

“Corruption can be defeated. Don’t give up”

Cătălin Rădulescu, a PSD lawmaker who received a suspended sentence of one-and-a-half years in 2016 after a DNA investigation into bribery, was also fiercely critical of the agency. (A criminal conviction is not an obstacle to serving as an MP in Romania, although it does preclude serving in cabinet.) Dragnea, Iordache, Pleşoianu and Rădulescu did not respond to requests for interviews or reply to emailed questions.

Kovesi’s enemies jumped on the sheer number of investigations she had launched during her two terms — many directed against PSD politicians — as evidence of a witch hunt. “It’s like a bear finding a jar of honey,” Calistru of Funky Citizen said, describing the relish of PSD lawmakers as they readied for a fight.

As Kovesi’s detractors set about portraying her as a taskmaster who would go to any lengths to pursue prominent scalps, they were helped by leaked recordings of DNA staff meetings in which she is heard chewing out prosecutors for working too slowly. “I want us to get the prime minister, who signed those contracts,” she is heard barking in one recording aired by Antena 3, a pro-PSD broadcaster, though Kovesi said the tape had been edited to take her words out of context. Other leaked recordings released by the TV station a few months later showed two DNA prosecutors apparently pressuring a witness to help them falsify evidence and saying Kovesi knew all about it. The prosecutors have since been charged with falsifying evidence.

The crest of Romania’s anti-corruption agency. Photo: © Octav Ganea

“Excess and failure”

Suggestions that Kovesi was trigger-happy in pursuing justice were compounded by high-profile cases that ended in acquittal, including the prosecution of PSD grandee and former Prime Minister Victor Ponta, cleared of bribe-taking and tax evasion this spring. Two months before Kosevi was sacked, former PSD lawmaker and party financier Sebastian Ghita was acquitted, in absentia, of influence-buying, blackmail, driving without a licence and profiting from confidential information. In an earlier trial, in September 2017, he had been acquitted of bribery and money laundering.

Ghita faced five corruption investigations, two of them ongoing, following DNA probes into allegations that he courted bribes in return for state contracts and illegally funded Ponta’s 2014 presidential campaign. Ghita fled to Serbia in 2016 and is fighting an extradition request. He denies the allegations. Others found not guilty of corruption-related charges during Kovesi’s tenure included Călin Popescu Tăriceanu, leader of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats, ALDE, the junior party in the PSD-led coalition; former Constitutional Court President Toni Greblă; and Sorin Blejnar, former head of Romania’s fiscal authority.

Justice Minister Tudorel Toader has overseen a series of judicial reforms that have triggered anger at home and condemnation abroad. Photo: © George Calin

“Excess is not healthy,” Stefan said. “And I see excess and failed cases.” Today, the DNA’s caseload is anything but excessive. The agency reported that it opened three new cases in September, all relatively minor. That compared with 32 in the same month of 2016, when it started investigating Ponta, Ghita, Deputy Prime Minister Gabriel Oprea, Interior Minister Petre Tobă and four mayors, all suspected of various forms of corruption. Aside from Ponta’s case, which ended with acquittal pending appeal, and Oprea being charged, all other investigations are ongoing. They all claim to be innocent. Interim DNA chief Anca Jurma, Kovesi’s former advisor on international relations, has kept a low profile while the agency awaits a new director.

In July, Justice Minister Toader rejected six candidates nominated for the job, including Kovesi’s deputy, Marius Iacob, and the head of the DNA unit investigating judicial corruption, Florentina Mirică. Since then, another six have entered the running. Only one has worked for the DNA.

“Serbia’s Kovesi”

Romania gained EU membership by adopting an anti-corruption strategy that hinges on the work of a prosecutorial agency handling high-level corruption and misuse of EU funds. The model was inspired by similar institutions in Spain, Belgium and Norway.

Neighbouring Serbia, which also has EU aspirations, took a different approach, creating two graft-fighting bodies with no powers to prosecute: the Anti-Corruption Agency, ACA, and the Anti-Corruption Council. In a country plagued by “endemic corruption”, as Transparency International puts it, experts say Serbia’s two institutions have few tools to take action.

For example, the ACA is in charge of making sure public officials are transparent about their assets. Yet it has no sanctions at its disposal other than the ability to slap officials on the wrist with warnings or recommendations that they be fired.

Transparency advocates say political interference from the ruling Serbian Progressive Party is another impediment. The director of the ACA is a former party member and donor. Neither the Progressives nor the ACA responded to questions.

Nemanja Nenadić, programme director at Transparency Serbia, said the Anti-Corruption Council had “no powers whatsoever”. “It’s a strange institution, pretty much unique in the world,” he said. “They have a good reputation because they were proactive and investigated some cases on their own, but it looks like something a good journalist would do – collecting and analysing data.”

The council is supposed to have 13 members, including a chair, but currently has seven. The members are not necessarily legal experts though they are “people of good standing in society who have no political affiliations and no agenda”, said Vice-Chair Miroslav Milićević, a retired surgeon. Through its research, the council has uncovered more than 20 cases of illegal privatisations in Serbia and shed light on political influence through media ownership, experts say. But many attribute those successes to one person in particular: Verica Barać, who served as chair of the council from 2003 to 2012, when she died of cancer. “She was a very brave human rights fighter, who used to protest against the war and [Serbian strongman] Slobodan Milošević, and against moguls,” said Milićević, who was her friend and doctor.

Many people saw Barac as Serbia’s equivalent to Laura Codruta Kovesi, former chief of Romania’s National Anti-Corruption Directorate. Both had reputations for aggressively pursuing senior government officials. Barać’s picture stands on a coffee table in Milićević’s office at the council, next to a bouquet of dark roses. “She was a person who could inspire others,” he said. “She spent all her energy, all her health on this. And that’s what’s hurting us today: we have put in so much, but what are the results?”

Among the new crop of nominations is Toader’s personal pick, Adina Florea, a 52-year-old prosecutor from the Black Sea city of Constanta, daughter of a PSD local council member. Toader said he would send President Iohannis his proposal to name Florea as the next DNA chief even if the Superior Council of Magistracy, CSM, the independent body that regulates judges and prosecutors, failed to approve her.

On 19 October, the CSM rejected Florea, who recently testified as a witness in an ongoing case concerning another declassified protocol between the General Prosecutor’s Office and the secret service, which surfaced in the autumn. True to his word, Toader put her name forward anyway. He did not respond to requests for comment.

In making her case for why she should be appointed, Florea submitted a report bristling with criticisms of the DNA, available on the justice ministry’s website. Much of the document echoes reproaches made by Toader in an evaluation of Kovesi in February, when he called for her dismissal.

These included claims that Kovesi acted in a discretionary manner and exceeded her powers; that she failed to act when prosecutors were accused of ethical breaches; that she favoured star prosecutors working on high-profile cases; and that she pursued vendettas rather than bulletproof investigations. “Even at a top level, we saw a type of behaviour that departed from a balanced, professional approach,” Florea wrote. During an interview with Antena 3 in September, Toader said the way Florea “exposed the good and the less good in the DNA” in her report had convinced a commission at the justice ministry that she was the right person for the job.

President Iohannis rejected Florea as head of the DNA in late November, using a legal technicality. He said she had not yet passed checks into whether she had ever collaborated with the Securitate secret police in the days of communism — a requirement for all prosecutors and judges seeking top positions. Toader countered that such a technicality was not Iohannis’ to invoke, saying that it was up to the CSM, not the president, to screen prosecutors. The impasse continues. Whatever happens with Florea’s nomination, her employment prospects look secure.

In mid-October, she landed a job as deputy chief in a new special unit of the General Prosecutor’s Office set up to investigate prosecutors and judges. The department was launched as part of the justice reforms introduced by the PSD-ALDE coalition. Previously, the prerogative to investigate judges and prosecutors belonged to the DNA. Florea and the head of the department, Florena Esther Sterschi, are seeking to turn the unit into a directorate, like the DNA, independent of the general prosecutor. Adina Florea declined to comment but numerous local media have quoted her as saying she will accept the job of DNA chief if the president ends up offering it to her.

“Problem of independence”

Transparency activist Calistru described the selection process for Kovesi’s replacement as “a kind of show staged by Tudorel Toader to show that the justice minister is the chief of all prosecutors”. “We have a big problem about the independence of prosecutors,” she said. “If we take a look at Hungary, where [Prime Minister Viktor] Orbán also reformed the judiciary, the biggest problem there is that the number of cases that reach a judge’s desk has decreased. “You can have the most independent, competent judges in the whole world. As long as you can’t investigate cases, you’re stuck. That’s why prosecutors have a fundamental role.”

In a Flash Eurobarometer survey of 201 people in January on perceptions of justice systems, Romania scored lower than the EU average on all indicators. Romanians no longer think judges have sufficient guarantees of independence and see them as being pressured by the government, politicians and interest groups, it showed. At his rally in June, PSD strongman Dragnea assured supporters that the government’s justice reforms would continue as planned, whatever the “beneficiaries of the illegal system of power” might think.

Adina Florea, the justice minister’s personal choice for the next head of the anti-corruption agency. Photo: © Octav Ganea

Meanwhile, critics of the government say the knives are out for Kovesi’s former boss and ally, General Prosecutor Augustin Lazăr, whom some see as the last man standing between the PSD-led parliament and a justice system under siege. Lazar, 63, is known for launching prosecutions against former President Ion Iliescu and former Prime Minister Petre Roman for crimes against humanity during Romania’s anti-communist uprising in 1989, in which more than 1,000 people died. His office is also investigating the actions of riot police after authorities responded to anti-government protests on 10 August 2018 with tear gas and water cannons. One person died several days later and 400 were injured.

Justice Minister Toader announced on Facebook in late August that he was sending an evaluation commission to look into Lazăr’s tenure as prosecutor general — the same process that led to Kovesi’s dismissal. Initially, Toader cited the discovery of a protocol, apparently signed by Lazăr in 2016, between the general prosecutor’s office and the intelligence services allowing prosecutors to access secret surveillance data for investigations. On 24 October, however, Toader announced he was officially starting the dismissal procedure for Lazăr on the grounds that he had not had a personnel evaluation before entering the general prosecutor’s office. Implying that Lazăr had got the job fraudulently, Toader asked President Iohannis to fire him.

“How can we build cases when everything we’re working on is dismantled?”

At an emotional news conference that evening, Lazar said the ministry was trying to destabilize the justice system. “How can we build cases when once every few months everything we’re working on, a team of professionals, is dismantled?” Lazăr asked. “Please forgive my emotional state, but what I’m telling you now is not indifferent to me and I feel like I’m living a very special moment, not just for my career, but for Romania.” A few days later, Lazăr announced he was suing Toader for unfair dismissal. Lazăr declined an interview request, citing a full schedule.

The European Commission has been fiercely critical of PSD-led attacks on the justice system. In a report published in November, the commission urged Romania to “immediately suspend” implementation of new laws on justice, changes to the criminal code and emergency decrees that make up the ruling party’s package of reforms.

It also called for a stop to dismissals or appointments of chief prosecutors and for the justice ministry to restart the procedure for naming a new DNA chief. European Commission Vice-President Frans Timmermans said at a press conference that pressures on the justice system in general “and the DNA, especially, as well as a series of other measures that undermine the efforts to fight corruption, resulted in forms of regress that are regrettable”.

The General Prosecutor’s Office took the opportunity to release a statement pledging its commitment to trying to fulfil the commission’s recommendations. Analysts say such words might not mean much these days. “Think of the judiciary as a winter jacket,” said justice system expert Vrabie. “It was a little short in the sleeves, but instead of fixing that, Romanian politicians decided to replace the zipper with buttons. The buttons don’t fit, so now the jacket doesn’t close, and it’s cold outside and the sleeves are still too short.”

[Editor’s update, July 2019: Prosecutor General Augustin Lazar was dismissed in April 2019 by President Klaus Johannis by mutual agreement. In a referendum on 26 May 2019, a large majority of the Romanian people voted for a tough anti-corruption course. The verdict against Liviu Dragnea became final on 27 May 2019, and the head of the Socialist Party was jailed.]

First published on 6 December 2018 on Balkaninsight.com.

This text is protected by copyright: © Ioana Burtea, edited by Timothy Large. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Laura Codruta Kovesi, former head of National Anti-Corruption Directorate. Photo: © Octav Ganea

This article was produced as part of the Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation and Open Society Foundations in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.