16 February 2023

Originally published

27 January 2022

Source

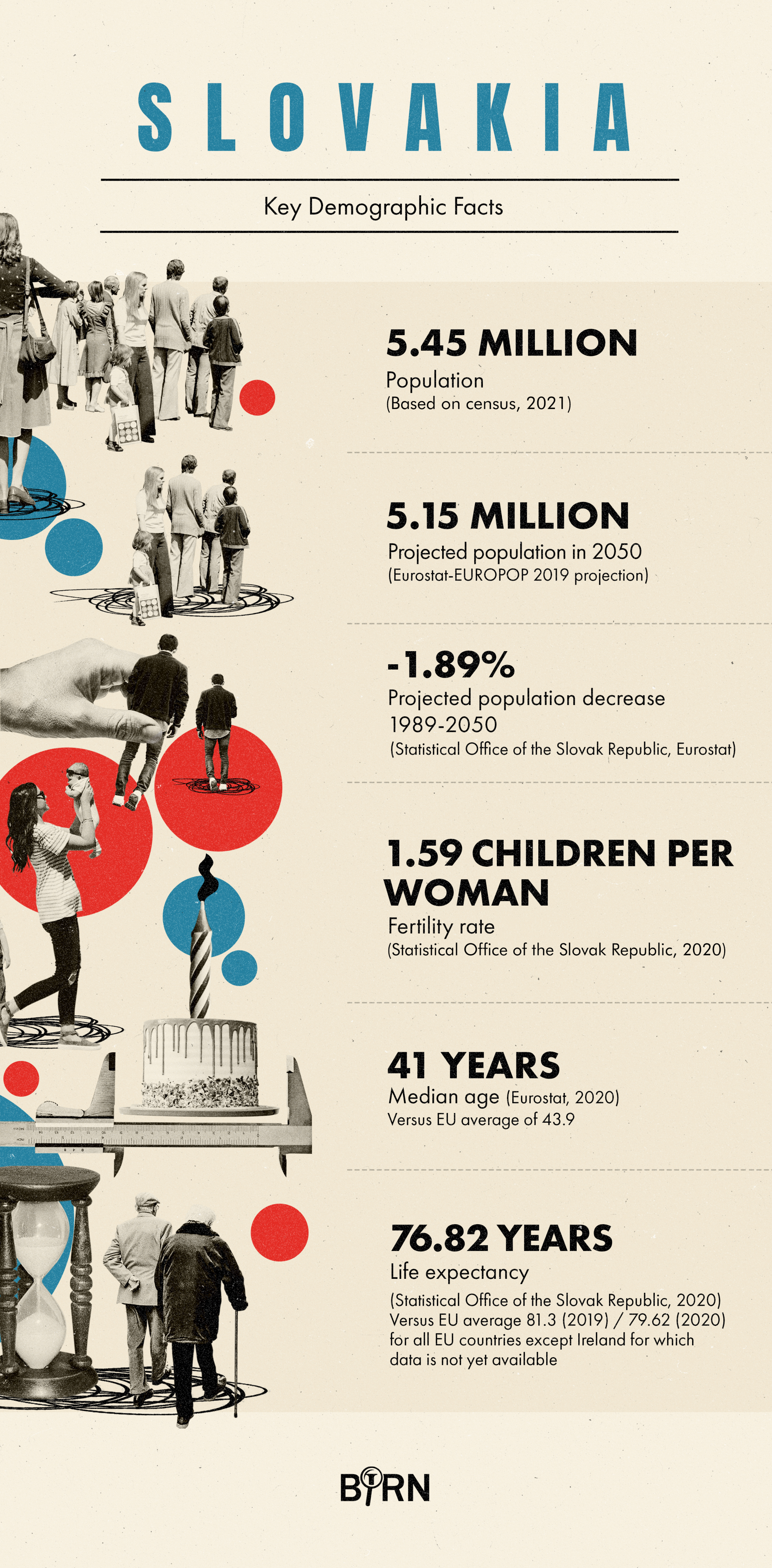

Slovakia has released data based on the 2021 census indicating its population is set to age fast. But the demographic situation could be even worse over suspicions there are a lot less people in the country than the official data suggests.

A kindergarten class winds its way past the Slovak National Galley before turning on to the busy main road along the Danube. The kids are being shepherded by three 30-something women who could well be mothers of children this age. The column of children squeezes past two elegant old ladies chatting and ambling slowly along the pavement.

A few minutes away, in front of the famous Roland Fountain in Bratislava’s old town, a handful of teenage girls are sitting on the ground taking part in the weekly Greta Thunberg-inspired School Strike for Climate. In a year or two they might well be enrolled in the capital’s Comenius University which, in pre-COVID times at least, bustled with busy students. If any of the girls decides to study demography there, they might be in for a few surprises.

First of all, there are a lot less students than there used to be. In 2008 there were 214,309 in higher education in the country, but by 2020 there were only 116,124. Students studying abroad account for some of that – but not all. There are just a lot less Slovaks of university age and, by contrast, more pensioners every year. There are also ever less people of working age, and unless more migrants come to Slovakia, what are already serious labour shortages will turn critical.

Infographic: Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

Slovakia’s population will soon start to shrink if it has not done so already, and its people are ageing. That is no surprise. Those are the same trends elsewhere in much of Central and Eastern Europe. What’s alarming demographers, however, is that that while Slovakia’s total population has remained relatively constant for years, they are uncertain about the accuracy of official population data. Yet for Ludmila Ivancikova, director for demography at the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic, the bottom line is that Slovaks are not only ageing rapidly, but they are ageing at a much faster rate than their neighbours.

Getting old… fast

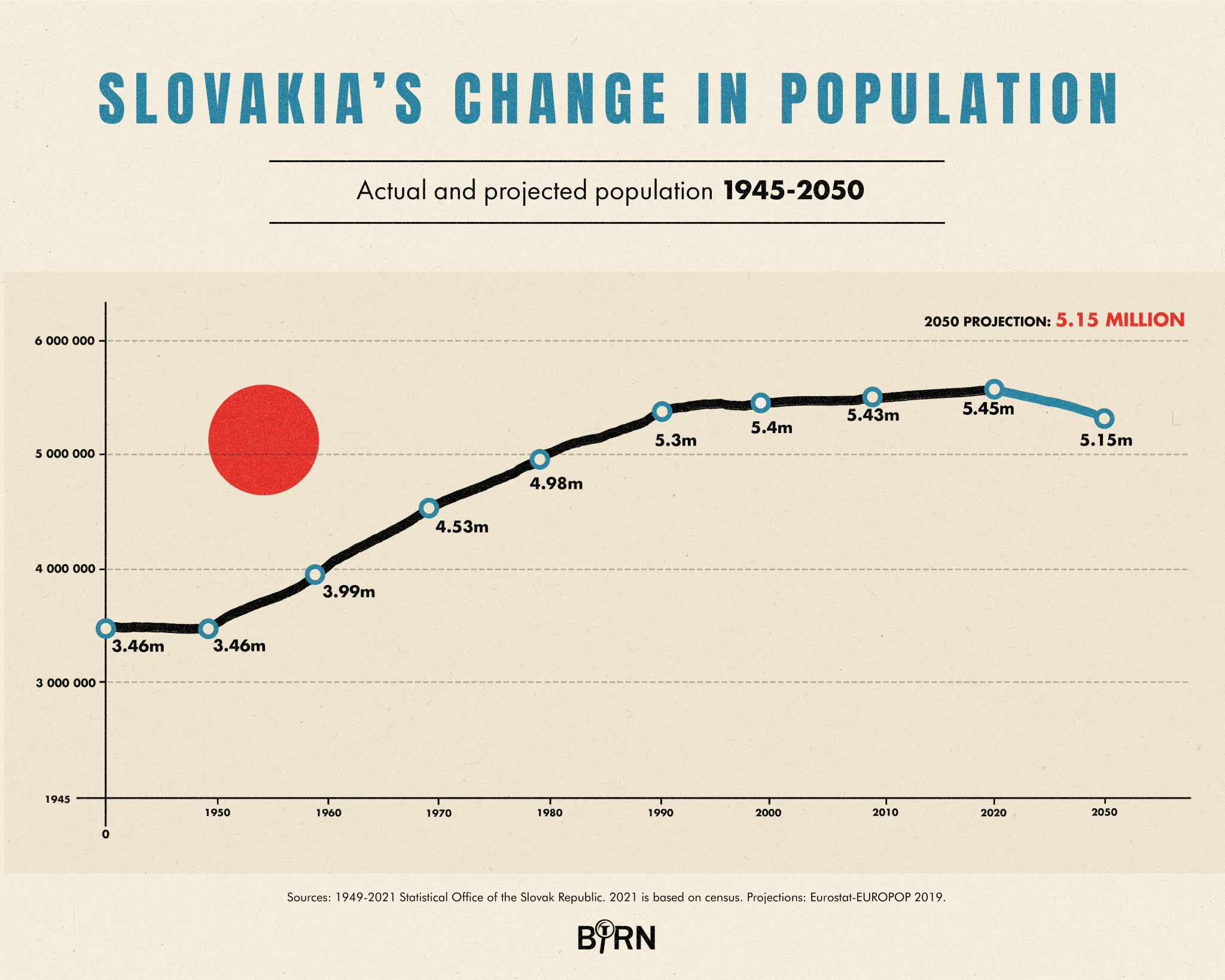

In December [2021, editor’s note] the Statistical Office released the first data based on the 2021 census. It revealed that on 1 January 2021 there were believed to be 5,449,270 people in the country. If that figure is right, it means that the total number of people in Slovakia was then 45,000 more than a decade previously and 166,270, or 3.1 per cent, more than in 1991.

According to Slovakia’s Ministry of Interior, there were 152,902 foreigners living legally in the country in the middle of last year. They made up 2.8 per cent of the population. Until Slovakia joined the EU in 2004, there were very few foreigners living in Slovakia. So, if you subtract them from the country’s total population, as many – including Ukrainians and Serbs, the two biggest groups – are only in the country on temporary work visas rather than as immigrants, then it would seem as though the country’s population was almost the same as 30 years ago.

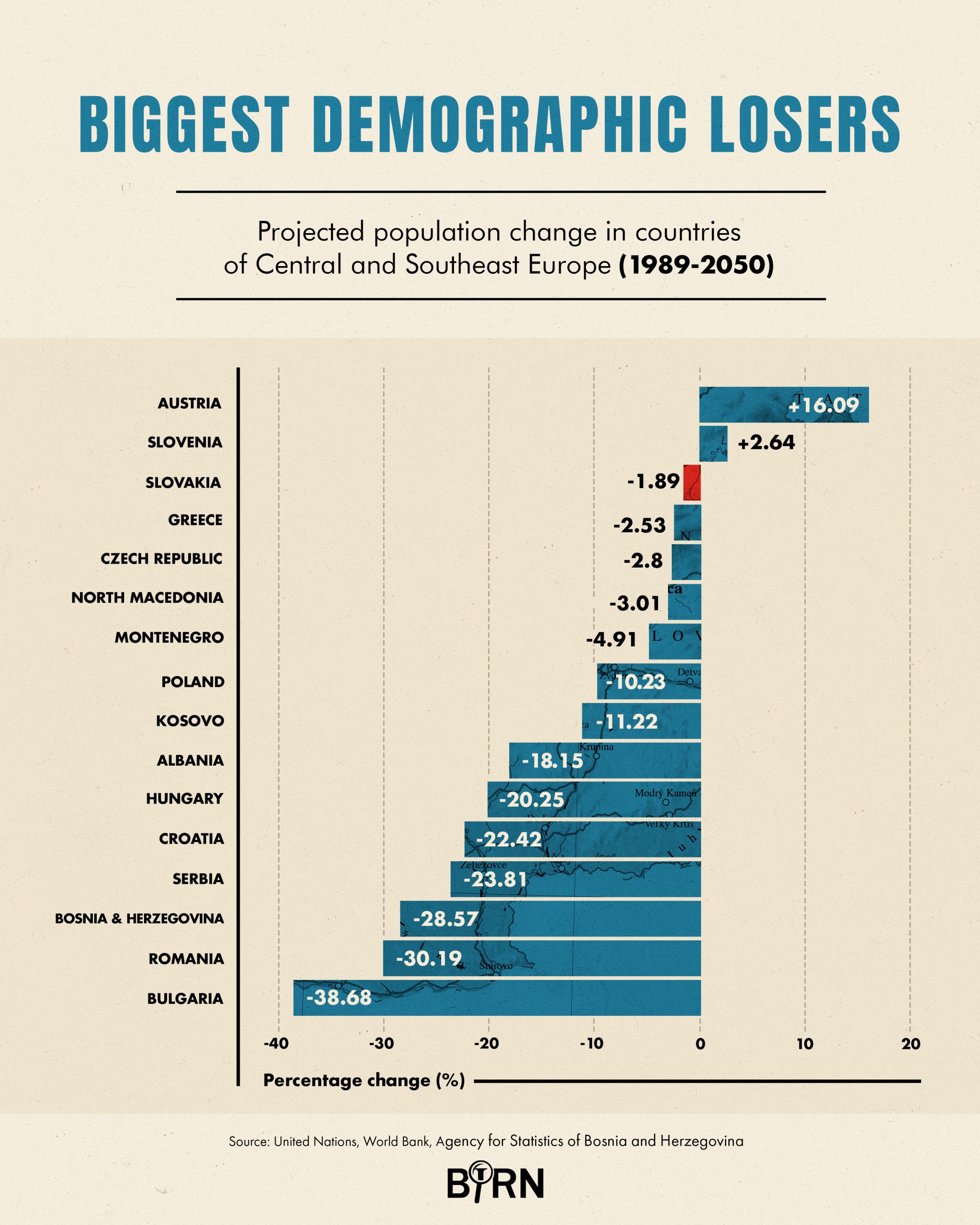

Since the populations of all of Europe’s former communist countries, except for Czechia and Slovenia, have shrunk, often quite dramatically, in the last three decades, this would seem to be something to celebrate. In fact, it would be very premature to crack open the champagne.

Infographic: Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

In 2011 Slovakia’s population comprised 832,572 children aged up to 14, plus 3.88 million people aged 15-64, and 690,662 people aged 65 and above. At the beginning of 2021, based on the census data, it had 867,410 children, 3.65 million people of so called “productive age”, and 929,181 older people. In only ten years, the number of elderly had shot up from 12.78 per cent of the population to 17.05 per cent, while the number of people of working age had shrunk from 71.81 per cent to 67.03 per cent. The percentage of children had grown by only half of 1 per cent. And the projections do not look good.

According to Branislav Bleha, head of demography at Comenius University, by 2060 under the most likely scenario, the number of people of “productive age” will plummet to 2.66 million, but the number of those aged 65 and above will balloon to 1.77 million based on projections of an optimistic assumption that the total population will only have declined to 5.43 million, even though it is possibly less than that already. According to a projection by Eurostat, the EU’s statistical agency, Slovakia’s population could have fallen to 4.95 million in 2060.

Whether Slovakia is prepared for such a big drop in its labour force and simultaneous increase in the number and proportion of pensioners remains to be seen. State care homes for the elderly are already underfinanced and, with so many care staff working for better wages abroad, they are already understaffed, as are private care homes. According to Jan Bucek, professor of human geography at Comenius University, for years experts have been providing successive governments with facts, figures and recommendations. But he laments that as “science and expertise are not fully respected”, their suggested strategies for coping with the coming rapid and massive ageing of society are neither properly followed nor implemented, and then “they are always replaced by new ones.”

Behind the ‘Hajnal Curtain’

All European countries are ageing, but what sets Slovakia apart is the speed of the change. In the 1980s Slovakia was one of the youngest countries in Europe. In the coming decades it will be one of the older ones. In 1965 John Hajnal, a British statistician, drew a line from St Petersburg to Trieste and hypothesised that, for cultural reasons, women east of the line tended to marry earlier and have more children than their counterparts to the west.

The so-called “Hajnal line” has long been regarded as controversial and, especially in this century, become discredited or, as the facts have changed, simply passed its expiry date. And yet it still strikes a chord in the former Czechoslovakia as the line divided its two component parts, which have indeed followed different demographic trajectories. In communist times, Slovaks had a significantly higher fertility rate than Czechs. Bleha says that the reasons for this include the country’s larger rural population, the fact that it was less industrialised than Czechia, and that its people were generally more religious and conservative. In 1989, at the moment of the collapse of communism, the Czech fertility rate was 1.85 and Slovakia’s was 2.09. Then something extraordinary happened.

Infographic: Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

With the dislocation and economic collapse that followed, the fertility rates in both countries plummeted – as they did elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe – but that of Slovakia fell much further and faster than that of Czechia. The reasons for this included the much tougher economic situation in Slovakia, a greater emigration rate of younger people and a fast adoption of new values. Ever since 2004 Slovakia’s fertility rate, then at 1.23, has been lower than Czechia’s but, as in Poland and Hungary, it has been drifting upwards since then.

In 2020 Slovakia’s fertility rate was 1.59, just above the EU average of 1.53. As there are less women of childbearing age than before, it means that fewer women are having more children. In 2016 women of childbearing age were 47.1 per cent of the total, but by 2020 that figure had dropped to 45.47 per cent. So many Slovaks live abroad that about 10 per cent of newborn citizens are estimated to be born outside of the country, according to Boris Vano, an analyst at the Demographic Research Centre.

As they are not born in Slovakia though, they don’t figure in the country’s fertility rate calculations. The previous high rate of fertility followed by its dramatic fall is the reason why Slovakia faces an equally dramatic process of ageing in the coming years. Another contributory factor is emigration, especially of women of childbearing age. Both of these factors mean that Slovakia’s population should, according to Ivancikova, start to shrink in the period 2030-40.

Is Slovakia already shrinking?

The problem is that no one knows how many Slovaks have left, how many have come back and whether Slovakia’s official population data is accurate. If it is not, then it means the country’s population has already begin to shrink – and quite dramatically at that. The likely reason behind the discrepancy is that many people leave Slovakia but retain an official address at home or they commute back and forth. For example, some 24,000 women, many from eastern Slovakia, are believed to work much of the year in Austria caring for elderly people. Many others commute, coming home for a period every few weeks or months.

Bratislava ‘School Strike for Climate’. Photo: Tim Judah

Interviewed just before the release of the new population data based on the census, Bleha said that he and his colleagues believed that there could well be 200,000 people less in Slovakia than official data suggests. These could include some of the more than 21,000 students who study every year in Czech universities and then stay there, plus doctors and other medical professionals who find better pay and conditions there. After the new data was released, Bleha said that while it was clear that several methodological issues had bedevilled the census, he and his colleagues did not yet have enough information to be able to confirm or put aside their suspicions that there are a lot less people in the country than the new figures suggest.

If the new numbers are an overestimation, it would not be a surprise, although Ivancikova at the Statistical Office said that great care has been taken to cross reference different registers and statistical sources. In 2017 Martin Halus, working on his PhD, made an estimate of population trends based on the number of people with health insurance. This is compulsory, but generally those that leave the country de-register so they do not have to continue paying it. This led him to conclude that in 2015 there were 300,000 less people living in the country than the official data suggested. For this reason, said Tomas Sobotka, a demographer with the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital in Vienna, the figure cited by Bleha before the new census-based data came out was realistic, although he adds the caveat that it is difficult to arrive at an exact number. For example, by the end of September 2021 there were 106,820 Slovaks who had received the right to settle in the post-Brexit UK and, in the latest figures, there were 45,362 Slovak residents in Austria.

However, some of those in Austria could be carers who also remain registered as living in eastern Slovakia. The British number also does mean that so many Slovaks are actually in the UK. A proportion of those who applied to live in the country could be Slovak Roma amongst others, who have since returned home to Slovakia having for now kept open an option for them and their families to live and work legally in the UK if they need to. Unreliable population data is an issue not just because it makes government planning hard. In Slovakia, local authorities receive money from central government based on the number of people living there according to the census.

Today, there are estimated to be some 600,000 people living in Bratislava, using its municipal services and so on, but according to the census-based data there are only 475,503 whose taxes effectively support everyone. When the figures were published in December the mayor demanded an explanation, saying that at least 20,000 more people are registered in the city than the census figures show, while another 100,000 live there who are registered somewhere else.

If not now, when?

Slovakia is not the only European country whose officials are struggling to work out how many people actually live there. It is also not the only country whose politicians need to grasp the nettle of planning beyond their next date with the electorate. According to Vano, for example, the topic of ageing will become critical in a decade, but “for our politicians that is too long term.” The problem, he noted, is that in 10 years they will find it is too late to do something, even if they were in power now, when it is not.

First published on 27 January 2022 on Reportingdemocracy.org, a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The article was produced within the framework of the Europe’s Futures project.

This text is protected by copyright: © Tim Judah. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team. Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations or on top of the article. Cover picture: Illustration: Ewelina Karpowiak / Klawe Rzeczy

Reporting Democracy

Reporting Democracy is a cross-border journalistic platform dedicated to exploring where democracy is headed across large parts of Europe. Besides generating a steady stream of features, interviews and analytical pieces done by own correspondents, Reporting Democracy supports local journalists by commissioning stories and providing grants for in-depth features and investigations. The Fellowhsip for Journalistic Excellence is part of Reporting Democracy. Both is being realized and run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) and supported by the ERSTE Foundation.