13 February 2019

Originally published

16 January 2019

Source

A year after the murder of Kosovo Serb politician Oliver Ivanović, a slew of gun and bomb attacks in Kosovo’s lawless north remain unsolved. First they blew up his car. They torched his party’s headquarters. Someone broke into his home and threatened his wife. Then they blew up his car again. “They did everything they could up til now — apart from shoot me,” Oliver Ivanović, a prominent Kosovo Serb politician, half-joked during a television interview in November 2017. Almost three months later, at around 8.10 a.m. on 16 January 2018, Ivanović was walking to his party’s headquarters in the northern Kosovo town of Mitrovica when six shots rang out from a moving vehicle. Hit in the back, he was dead within the hour.

“He always told me: ‘You know that Kosovo is my life,’ and in the end, he has really given his life for Kosovo,” his widow, Milena Ivanović Popović, told the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) shortly before the first anniversary of his death.

At the time of the shooting, Ivanović was on trial for war crimes against Kosovo Albanian civilians at the tail end of conflict in the 1990s — charges he denied. But in a town synonymous with strife between Serbs and Albanians, few thought of Ivanović’s murder as ethnically motivated. In several public statements, Ivanović had blamed criminal elements within the Kosovo Serb community for past acts of intimidation. He also alleged they had ties to the Belgrade-backed Serb party in Kosovo. The party is Srpska Lista, and Ivanović had been a vocal critic.

Candles burn in tribute to Kosovo Serb politician Oliver Ivanović, who was murdered in front of his party’s headquarters in the northern Kosovo town of Mitrovica on 16 January 2018. Photo: © Sasa Djordjevic / AFP / picturedesk.com

Police have named Milan Radoičić, Vice-President of Srpska Lista, as a suspect in the murder case. Radoičić, whom Ivanović once described as the real powerbroker in Serb-run enclaves of northern Kosovo, has evaded arrest and remains at large. He denies involvement in the killing. Kosovo police have meanwhile arrested two Serb officers from the country’s recently integrated police force and a member of a Partizan Belgrade football fan club in connection with the murder, though the Kosovo Special Prosecution has so far been unable to identify the person who pulled the trigger. A year after Ivanović’s slaying made global headlines, a BIRN investigation reveals that the crime is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to unsolved cases of suspected political violence within the Serb community in northern Kosovo.

The crime on Oliver Ivanović is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to unsolved cases of suspected political violence within the Serb community in northern Kosovo.

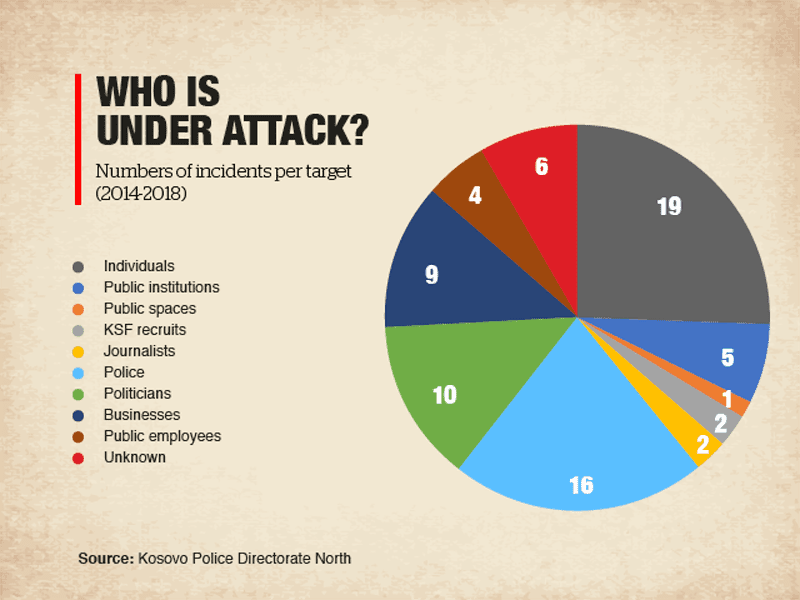

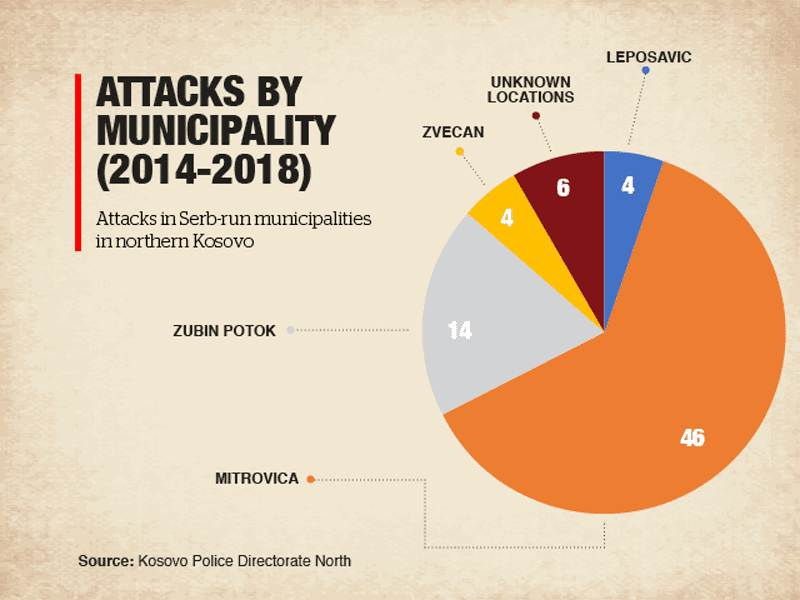

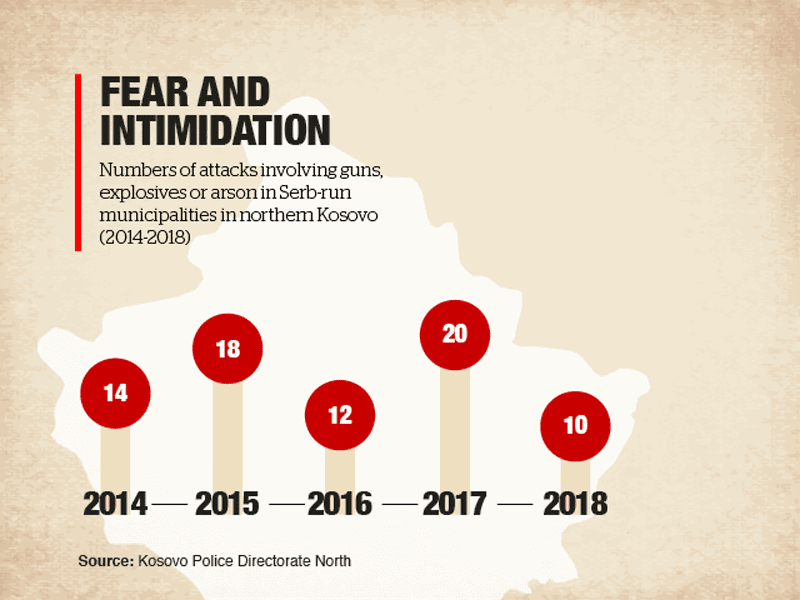

As the murder casts a pall over EU-sponsored efforts to normalise relations between Belgrade and Pristina, BIRN has catalogued 74 attacks on Kosovo Serbs involving guns, grenades, arson or explosive devices since 2014, the year Srpska Lista first took power after landmark local elections. Targets include politicians, members of the police or security forces, journalists, entrepreneurs and employees of state institutions. Kosovo police are not treating any of the cases as ethnic violence, meaning they do not think Kosovo Albanians are behind the attacks.

Aside from the murder of Ivanović and another opposition politician four years earlier, none of the incidents has been lethal — though locals say the attacks have raised the fear quotient in a part of Kosovo long known for lawlessness. Most incidents involved the destruction of cars or property and happened late at night, leading crime experts to speculate that perpetrators may be more interested in sending a message than maiming or killing. As of the time of publication, not one case has led to a prosecution. “I’m not satisfied,” Shyqyri Syla, chief prosecutor of the Basic Prosecution of Mitrovica, told BIRN. “You see there have been cases since 2014 and no one has been identified. Four years have gone by and the more time passes, the harder it is to detect the perpetrators.”

BIRN’s findings are the result of six months of combing through local media reports and interviewing residents and officials. BIRN has confirmed the details of each case with the local prosecutor’s office and the Kosovo Police Directorate North, which has police stations in the Serb-run municipalities of Mitrovica North, Zubin Potok, Zvečan and Leposavic. It is difficult to make comparisons with crime levels prior to 2014, the year an integrated Kosovo police force was established for the whole country under an EU-brokered accord to end ethnic partition in Kosovo. Accurate statistics for Serb-run enclaves are simply not available. But asked about car-bombings and other incidents before 2014, the Department for Serious Crimes at the Basic Prosecutor’s Office in Mitrovica said police opened only five investigations into such cases between December 2000 and December 2013. All remain unsolved.

While there is no evidence that Srpska Lista leaders are themselves lobbing grenades or Molotov cocktails, critics accuse the party of creating a climate of fear and intimidation that some say is tantamount to inciting violence. They also say the ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) in Belgrade is happy to fan the flames of discord that some say legitimise the attacks in a part of Kosovo that has long resisted ethnic integration. “I don’t know what else to call it other than ‘state-sponsored crime’ happening under the pretext of maintaining the Serb community in the north,” said Bojan Elek, a researcher at the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy think tank. Neither Srpska Lista nor the SNS responded to interview requests or written questions about the findings of the investigation.

Divided worlds

The Ibar Bridge in central Mitrovica is an enduring symbol of the town’s ethnic animosities. Serbs live to the north, Albanians to the south. The Ibar river carves a line of separation in between. The 30-metre bridge was a notorious flashpoint during and after the Kosovo war in the 1990s. Today, it is still closed to traffic. But for pedestrians, it offers a tantalising glimpse into different — and divided — worlds.

On the south side, Albanian-speaking stallholders sell Albanian and US flags. Cash machines dispense euros. A mosque looms over a bustling market square. On the north side, Serbian-speaking shopkeepers deal in dinars as bells peal from Orthodox churches. Signs are written in Cyrillic. Many businesses will not accept credit cards or issue receipts, and some cars lack licence plates — signs of legal limbo in the Serb-run enclave.

Three blocks to the northeast of the bridge is the office of Civic Initiative Freedom, Democracy, Justice (SDP), the main local opposition party in northern Kosovo. It was here that Oliver Ivanović was trying to revive his political career, running for mayor of Mitrovica North in local elections in October 2017, just months before he was shot. He was fresh out of prison after three years in custody while on trial for allegedly ordering the murder of Kosovo Albanian civilians in April 1999 when he was one of Mitrovica’s “bridge-watchers”, a term used to describe Serb nationalists dedicated to keeping ethnic Albanians out of the northern half of the town.

A mural in the northern half of Mitrovica glorifies Serbian soldiers who fought under the colours of the Yugoslav flag during conflict in Kosovo in 1999. “It is worth dying for this country,” reads the text in Cyrillic. Photo: © Stefan Milivojević

In January 2016, an EU-run court had sentenced him to nine years in jail. Ivanović appealed, arguing that the trial was politically motivated. In February 2017, an appeal court in Pristina overturned the conviction, ordered a retrial and set him free in the meantime. Ivanović was a paradox: an alleged war criminal with a reputation as a political moderate; a staunch opponent of Kosovo independence who spoke fluent Albanian and advocated peaceful coexistence with his non-Serb neighbours. Moving into national politics after his “bridge-watcher” days, he became a proponent of post-war dialogue with Albanians, who make up 91 per cent of Kosovo’s population, according to the latest census.

Between 2008 and 2012, he served as secretary of state for Kosovo in the Serbian government, forging a reputation as a man Pristina could cooperate with. Because Serbia does not recognise Kosovo’s independence, Kosovo Serbs in the former province can stand in Serbian national elections. In 2012, Ivanović set up the SDP, urging Kosovo Serbs to help themselves by taking up positions in Kosovo institutions including the police and judiciary. He ran for mayor of Mitrovica North in 2013 local elections, losing to the newly born Srpska Lista.

Controversial Connections

Milan Radoičić, Vice-President of Belgrade-backed Kosovo Serb party Srpska Lista, is wanted by Kosovo police in connection with the murder of Kosovo Serb opposition politician Oliver Ivanović.

He denies involvement in the killing and remains at large. Court documents obtained by BIRN show that Radoičić has had several prior run-ins with the law.

In 2010, the Basic Court in Kraljevo, a town in central Serbia, convicted him of forging an identity card. The court gave him a conditional sentence of three months in jail if he committed another crime within a year.

The following year, the Prosecutor’s Office for Organised Crime in Belgrade charged Radoičić with unlawfully appropriating 32 trucks that he had leased and taken across the border to Kosovo. The Special Department for Organised Crime at the Higher Court in Belgrade found him not guilty.

In 2013, prosecutors in the southern Serbian city of Pirot indicted him for unlawfully profiting from construction work on a Serbian highway project by digging gravel without the relevant approval of the mining ministry.

Again, he was found not guilty, this time by the High Court of Pirot.

Milan Radoičić, Vice-President of Srpska Lista, meets Kosovo Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj in July 2018. Photo: © Kosovo Prime Minister’s Office/KoSSev

Repeated attacks

Ivanović was no stranger to intimidation. Unknown attackers twice blew up his car, in 2005 and 2017. Ahead of local elections in 2013, his party’s office was set on fire, though nobody was hurt, said Ksenija Božović, Vice-President of the SDP. A few months later, an intruder broke into Ivanović’s home while he was out, terrifying his wife, Milena. “A man with a hood broke into the apartment and began to break everything that was glass,” she recalled. “My son [Bogdan], who was then a baby, was sleeping in the other room. Bogdan started to cry and the man slapped me in the face and said: ‘That’s for your husband,’ and he ran away.” Police never caught the intruder.

“It is like life under a junta, but instead of the military, we are being ruled by a criminal gang,” Ivanović told BIRN shortly before his death. “Criminal structures standing behind local government are the true source of power in Mitrovica now, not the politicians, or institutions.” In his last interview with BIRN before his death, Ivanović identified Radoičić — then a little-known debt collector and truck owner — as a key figure in the murky system of power in Serb-run parts of northern Kosovo. “The centre of power is not within the municipality building — because the municipality building belongs to this other, informal centre of power,” Ivanović said.

After Srpska Lista appointed Radoičić as Vice-President in the summer of 2018 — surprising many commentators who had never heard of him — media reported that he had close ties to political elites in both Kosovo and Serbia, including Serbian President Vučić and Kosovo Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj. Haradinaj faced criticism in July after he welcomed Radoičić at his office for a meeting that one opposition lawmaker, Armend Zemaj, described as a “solemn reception” for a “suspect for organised crime, extortion, violence and frightening the citizens of northern Mitrovica”.

Rada Trajković, who leads a non-governmental organisation in Kosovo called the European Movement of Serbs from Kosovo, told BIRN: “When I talk to Haradinaj and he says, ‘He [Radoičić] is the man who gives me guarantees for everything we agree on for the north and he fulfills everything,’ it means he has the support of the [Serbian] state to do things his way without liability and to finish the business that works for Vučić and his policies.”

In November, Kosovo police raided Radoičić’s home in connection with Ivanović’s murder. At the time, he was in Serbia, which has no extradition agreement with Kosovo. Radoičić remains at large and BIRN has been unable to contact him for comment. After news broke that Radoičić was wanted by Kosovo police, prominent Serbian officials defended him. Marko Ðuric, director of the Serbian government’s Kosovo office, called him a “true patriot”.

“It is like life under a junta, but instead of the military, we are being ruled by a criminal gang.”

President Vučić told Serbian public broadcaster RTS: “Milan Radoičić is not Oliver’s killer. Kosovo police special units wanted to kill him in an arrest operation in order to assign responsibility for the murder of Oliver Ivanović to Belgrade. Such accusations would weaken the negotiating position of Serbia [in the ongoing Brussels talks with Kosovo to normalise relations].” Srpska Lista members also appeared in public wearing white T-shirts showing a map of Kosovo emblazoned with the colours of the Serbian flag and an image of Radoičić, along with the words “We Are All Milan”.

In November, Kosovo police arrested three others suspected of involvement in the murder: Dragiša Marković and Nedeljko Spasojević, both members of the Kosovo police force, and Marko Rošić, a Montenegrin man identified as a member of Partizan Belgrade fan club. The Kosovo Special Prosecution says in a document seen by BIRN that those arrested — as well as those still wanted for arrest — are suspected of aiding the murder by offering facilities or concealing evidence.

Oliver Ivanović’s car is seen gutted by fire after it was blown up by unknown attackers in July 2017. Photo: © KoSSev

“A political message”

Besides Ivanović, six other Kosovo Serb opposition politicians have been targeted — some more than once — by unidentified assailants over the past four years, the investigation shows.

Dimitrije Janićijević, 35, was gunned down outside his home in Mitrovica at 12.20 a.m. on 16 January 2014 — four years to the day before Ivanović’s slaying. Janićijević and Ivanović were friends. According to Ivanović’s widow, Ivanović was godfather to four of Jancijević’s children. A member of the Mitrovica Municipal Assembly, Janićijević was running for mayor in local elections for the Independent Liberal Party at the time he was killed. According to a doctor who examined his body, he sustained more than 10 bullet wounds in the chest and abdomen. No one has been arrested for the murder.

In a separate incident in Mitrovica three years later, the office of Slaviša Ristić was gutted by fire. Ristić was a former mayor of Zubin Potok who has been an independent lawmaker in Serbia’s parliament since 2016. “We’d practically just moved into the office,” Ristić told BIRN in an interview at a cafe in Belgrade across the street from parliament. “About a month after that, they burned it down. The police didn’t do anything.” The fire engulfed the office on 7 February 2017. Police were called to the six-story building at 3.35 a.m. after residents reported smelling smoke, a police spokesman said.

A local resident recalled that people in the apartments above the DSS office used knotted sheets to escape. Four children ended up in hospital with smoke inhalation, media reported. It is unclear how the fire started, but Ristić said he was sure it was arson. Nor was it the first time his property had been targeted, he said.

During the night of 24 April 2016, as the SNS was celebrating victory in parliamentary polls in Serbia since democratic elections began in 2000, Ristić was watching the results on television at home in Zubin Potok.

“My whole family was in the house, my brother too, and we were following the election results in disbelief when we heard ta-ta-ta — shooting in front of the house,” he said. “We all lay down on the floor, the children and my wife, and then after a few minutes when everything calmed down, my brother and I went out into the dark to see what was happening.”

They saw broken windows and the exterior wall of the house pockmarked by bullets. The next day, his wife found an unexploded bomb in the grass. For Ristić, there is no question that the perpetrators were Kosovo Serbs rather than ethnic Albanians. “The Albanians are attacking Serbs in enclaves in the south [of Kosovo], but in the north, I believe all these attacks are connected to Srpska Lista, because it only happens to people who don’t toe the party line,” he said. Local media have reported cases of Kosovo Albanians attacking Serb pilgrims on their way to Orthodox churches in parts of Kosovo south of the Ibar River.

In July 2017 in northern Kosovo, someone blew up a car belonging to Dragisa Milovic, a doctor who was running for mayor of Zvečan in that year’s local elections. Though from a different party, Milovic had entered into an informal alliance with Ivanović against Srpska Lista. “That morning, I was shocked — my family too,” Milovic told BIRN in an interview at the Mitrovica Health Centre, where he works as an orthopaedic surgeon. “It was clear to me that this was a threat and a political message.” Asked what that message was, Milovic said: “There was only one goal, and that was that Srpska Lista must win. The message for me was to withdraw from the election and for other people not to vote for me.”

Dragan Jablanović, a former Srpska Lista member who become an independent politician, was mayor of Leposavic when his home was firebombed in October 2015. Nobody was hurt. In May 2017, someone fired bullets at the building where his mayoral cabinet met. Meanwhile, an unidentified assailant threw a bomb at the home of Dražen Stojković, president of the municipal board of the Serb People’s Party in Mitrovica, at around 9 p.m. one night in December 2016, damaging the exterior.

Nebojša Vlajić, Ivanović’s friend and lawyer, was matter-of-fact about the violence. “That’s just the way things are here: a way to fight your opponent is to say, ‘Let’s throw a bomb,’” he said. Janjić from the Forum for Ethnic Relations said bomb attacks in northern Kosovo were so common that people had become inured to them — to the point of forgetting that they are, in his words, “acts of terrorism”. “It’s a means of introducing rules when there is no rule of law,” he said. Janjić added that the explosives of choice in northern Kosovo tend to be Yugoslav-era hand grenades and home-made “bottle bombs”, or Molotov cocktails. “That one [the Molotov cocktail] is a warning bomb,” he said.

“Pattern of intimidation”

All the politicians interviewed by BIRN said they believed they had been targeted because of their opposition to Srpska Lista — and by extension, to the SNS in Belgrade. Srpska Lista first contested local elections in Kosovo that spanned the end of 2013 and the beginning of 2014, about two years after the SNS got a grip on power in Serbia. The party is now part of a coalition government in Pristina. Holding nine out of 10 seats reserved for Kosovo Serbs in an assembly of 120 lawmakers, Srpska Lista has three ministers in cabinet.

On paper at least, both Srpska Lista and the SNS are committed to promises made in a 2013 agreement signed by Serbia and Kosovo in Brussels to integrate parallel state institutions in Kosovo and try to remove obstacles to normalising relations. But neither party recognises Kosovo’s 2008 independence and much of their public rhetoric is at odds with official policy towards the EU-sponsored political process, observers say. Analysts say Srpska Lista and the SNS are unhappy with lack of progress on the establishment of an association of Serb municipalities t0 represent Serbs’ interests in Kosovo, a part of the Brussels deal bitterly opposed by Kosovo opposition lawmakers.

On its website, Srpska Lista presents itself as the only Kosovo Serb party backed by the Serbian government. And certainly, the SNS gave the party its exclusive endorsement ahead of 2017 local elections. “The victory of Srpska Lista is of national and essential importance for Serbs in Kosovo,” Darko Glisic, head of the executive board of the SNS, said in a meeting with Srpska Lista candidates for local councillor while touring Zvečan in October that year.

Calling on Serbs to go out and vote for the party, Aleksandar Vulin, Serbia’s defence minister and former head of the government’s Office for Kosovo, said: “They know best that Srpska Lista is a link to the Serbian government…” Ðurić, Serbia’s current director of the Office for Kosovo, told a pre-election rally in Zvečan: “Srpska Lista is the only link of the people in Kosovo with Serbia.” Pro-SNS media in Serbia and Kosovo also pitched in, launching campaigns against opposition leaders that critics condemned as dirty. Several days before polls opened, TV Pink in Serbia and TV Most in Kosovo broadcast one-minute political advertisements — on the hour, every hour — showing Ivanović’s face superimposed over an Albanian flag. A narrator said he represented “people who betrayed our trust, people who have the support of Pristina”.

Five media rights associations in Serbia issued a joint statement strongly condemning the ad, calling it “a fierce violation of journalistic standards and codes but also a violation of election rules”. In the end, Srpska Lista won by a landslide in all 10 municipalities in which Serbs are a majority. In Mitrovica North, their candidate for mayor, Goran Rakic, got around 67 per cent of the vote, compared with almost 19 per cent for Ivanović. “The campaign environment for the first round of elections was marred by a deep pattern of intimidation within most Kosovo Serb communities, targeting non-Srpska Lista political entities and voters,” EU election monitors wrote in a report in February 2018. They added: “Before the official campaign period kicked off, violent incidents occurred, including the burning of vehicles of two prominent opposition mayoral candidates. Institutions functioning under the ‘Serbian system’ operating in Kosovo were involved in pressuring non-Srpska Lista candidates and their families, in some reported cases leading to the dismissal from their employment.”

“Let’s break their bones”

Alongside politicians, many of the attacks identified by BIRN appear to be against Kosovo Serb businessmen, officials or individuals who have refused to boycott Kosovo institutions.

The exterior of the Dolce Vita café in Mitrovica was set on fire in August 2016 after Kosovo Minister for Dialogue Edita Tahiri drank coffee there. Four months later, the town’s Hotel Saša was bombed after Tahiri visited it. Kod Draževica, a Serb-run restaurant on Gazivoda Lake near the Kosovo-Serbia border, was firebombed after Kosovo President Taci went there in late September 2018.

Kosovo Serb police officers have also been singled out for attack. Over the past four years, 11 have had their cars torched while three have had their homes damaged by explosives, BIRN’s investigation revealed. All the victims were members of the newly integrated Kosovo police force formed in 2014 under the terms of the Brussels accord. Around 280 Kosovo Serbs passed security checks that year to join the Kosovo police, according to Besim Hoti, deputy regional commander of the Kosovo police for northern Mitrovica. From that moment on, they effectively had targets on their backs, he said. Many received letters calling them “traitors” and containing death threats.

In some cases, they were targeted “because they did their job properly”, said prosecutor Syla, citing the example of two officers whose cars were firebombed after they investigated suspected drug-smuggling by Kosovo Serb underworld figures. “Sometimes it’s not in the interest of certain people that something is investigated,” he said. “Those who did the most work had their cars set on fire.”

“All those who try to find their future in the institution of the ‘Kosovo Army’ will encounter a fierce boycott by the Serbian community.”

Fear of reprisal

Prosecutors confirmed that as of January 2019, nobody had been brought to trial for any of the 74 attacks identified by BIRN. “For us, the most difficult crimes to solve are the car explosions,” said deputy regional police commander Hoti. “There are no traces, and citizens won’t report to police what they know because they’re afraid.” Hoti said he thought the number of people behind the attacks was fairly small. “It’s not like 200 people are doing this. There are two or three groups that are putting bombs under the cars.”

Many victims are reluctant to speak out due to fear of reprisal, said Syla, chief prosecutor of the Basic Prosecution of Mitrovica. “I’d say they are more afraid for their lives, that someone might find out that they’ve testified, rather than that they lack trust in the police,” he said. “They don’t testify because of that fear.” Declining to be identified, a businessman whose property has twice been bombed said: “I don’t trust anyone anymore. I can’t and won’t talk about it anymore. I live here. I have a family.”

One night in June 2015, someone fired a gun seven times through the office window of an independent news portal in Mitrovica called KoSSev. Nobody was inside at the time. Visitors can still see bullet holes in the glass and signs of police forensic work. “We live in a dangerous place and what scares me most is that the perpetrators are never found,” KoSSev editor-in-chief Tanja Lazarevic told BIRN. Five months later, one November night at around 2 a.m., attackers torched a car belonging to KoSSev journalist Nevenka Medić. “I can’t give any particular reason why this happened, but the fact is that before and after this, everything that contradicts the official opinion of local powers and politicians is punished in this city,” Medić said.

Elek from the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy described Serb-run parts of northern Kosovo as lawless zones controlled by mafia-like structures. “On the one hand, it seems that Pristina doesn’t have the will or the way to control the north except through institutions [that are in the process of being integrated],” he said. “On the other hand, Belgrade has an interest in keeping things as they are.”

Milena Ivanović Popovic, wife of the late Oliver Ivanović, looks into the camera at the headquarters of the Serbian government in Belgrade. Photo: © Stefan Milivojević

Analysts say a state of controlled chaos in northern Kosovo could strengthen Serbia’s hand in Belgrade-Pristina talks — and help Serbia hang onto Serb-dominated enclaves even if it ends up bowing to international pressure to recognise Kosovo’s independence. Some Serbian and Kosovo politicians have unofficially raised the possibility of an exchange of territory — swapping Albanian-majority areas in southern Serbia for Serb-majority ones in northern Kosovo. “I think that Belgrade is aware that it has to recognise Kosovo,” Elek said. “But it’s looking to get something from the negotiation process so that this recognition will be easier to accept by the citizens of Serbia, in the sense that they can say: ‘We did not lose the whole of Kosovo. We got the north.’”

Back in Belgrade, a year after her husband’s murder, Milena Ivanović Popović is still waiting to know who left her seven-year-old son without a father. “I cannot lose hope,” she said. “Oliver deserves — we all deserve — to find out who is behind this murder, who ordered it. I think that for every honest and just man in Serbia, that is important.”

First published on 16 January 2019 on Balkaninsight.com.

This text is protected by copyright: © Anđela Milivojević, edited by Timothy Large. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: A bullet hole is seen in the window at the headquarters of independent media outlet KoSSev in Mitrovica. Photo: © Stefan Milivojević

This article was produced as part of the Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation and Open Society Foundations in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.