Debate over the impacts of emigration and demographic decline in Southeast Europe too often neglects those at the coalface of the crisis — marginalised Roma communities.

In recent months, Reporting Democracy has published a series of articles on the critical demographic decline facing the Balkans and large-scale emigration from the region to countries across the European Union. Informative as the articles are, they fail to discuss how these issues affect the Roma minority. In fact, Roma people make up a considerable number of those who are compelled to emigrate from the Western Balkans.

This may or may not be a bad thing. Migration can open up opportunities for marginalised Roma communities — but only if the political, social and economic will is there to make these opportunities a reality.

In his articles, Tim Judah reminds us how difficult it is to work with reliable numbers when it comes to the actual populations in the Western Balkans and elsewhere, as well as migration levels to EU states. This is true when it comes to Roma communities, too. There is, however, data showing the extent of forced migration of Roma from the Western Balkans. These numbers hint at the sheer extent of antigypsyism — the specific form of racism towards Roma in these countries.

Between 2007 and 2017, EU states received more than 200,000 asylum applications from Roma people from countries in the Western Balkans: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia. This was merely the latest spike in a long history of (forced) migration of Roma from the region. Long before the breakup of former Yugoslavia, many Roma formed part of the country’s migrating workforce or sought asylum in Western Europe.

With the Balkan wars of the 1990s, the number of Roma who were compelled to leave their home countries further increased. Roma from former Yugoslav states asked for asylum in Western Europe or migrated to Italy. Meanwhile, Roma from Albania went to Greece. The statistics underline the scale of this exodus over the decades.

Between 1996 and 2001, experts estimate that around 65 per cent of the Romani population of Albania migrated to Greece. In 2003, more than 35,000 Roma from Kosovo were registered as rejected asylum seekers with a temporary residence permit (Duldung) in Germany, after they were forced out of Kosovo in the aftermath of the war.

Though it is difficult to determine the exact number of Roma, Ashkali and Egyptians who left Kosovo in 2014/2015, the figure could be up to 10,000, which would equate to a quarter of the overall populations of the three communities at the time. Between 2014 and June 2017, slightly more than 59,000 Roma from Serbia submitted asylum applications in Germany.

Between 2014 and June 2017, slightly more than 59,000 Roma from Serbia submitted asylum applications in Germany.

And over the past decade, Roma from Serbia have accounted for more than 80 per cent of asylum applicants in Germany, according to the German government. In 2014 alone, they accounted for 92 per cent. Overall, in the past decade in Germany, around 90,000 asylum applications may have been submitted by Roma from Serbia.

Among asylum applicants from what is now North Macedonia, Roma constituted the majority. For many years, they have accounted for 50 per cent of asylum applicants from Bosnia and Herzegovina. The proportion is only lower in Albania and Montenegro.

A Roma child rides a bicycle in his quarter in Mitrovica, Kosovo. Photo: © Hazir Reka / Reuters / picturedesk.com

The root cause of the discrimination and social exclusion that compells many Roma to leave is the antigypsyism that affects — directly or indirectly — all aspects of daily life: housing, employment, education, health, culture. In an article on Reporting Democracy, Alida Vračić discusses the consequences of the emigration of doctors and medical workers on the health sector and on “the elderly, children and women”. It is also worth raising the consequences for marginalised and poor communities such as the majority of Roma.

Roma face on the one hand widespread racism — antigypsyism — in healthcare. On the other hand, rampant corruption in health systems excludes poor people — and again, the vast majority of Roma are poor — from receiving treatment or medicine. As numbers of doctors and medical workers continue to fall, the situation will further deteriorate.

When talking about emigration from the Western Balkans, the situation of Roma should not be ignored. This is especially true since forced migration into the asylum system reflects only one aspect of the migration of Roma from the Western Balkans.

With the tightening of asylum regulations and procedures in Germany, the number of asylum applications has fallen considerably. However, the situation for Roma in their home countries has not improved. Antigypsyism still excludes the majority from society and especially from the labour market, forcing them to look for other coping mechanisms.

Antigypsyism still excludes the majority from society and especially from the labour market, forcing them to look for other coping mechanisms.

Some make use of visa-free travel and buy clothes or other goods in Western Europe to sell back home. Others use visa-free travel to work (informally) in Western Europe for periods a little under 90 days, briefly return home and then go back again. Others stay informally for a long period without registering and without a regular job. Some work formally in Western Europe.

It is worth noting a discrepancy between the number of Roma whose asylum applications have been rejected and the number who have actually returned to their countries of origin — suggesting that some have stayed informally or found other ways to remain in Western Europe. Those who do return often face problems. In Kosovo, Roma who have been forcefully repatriated have found themselves with no access to housing or jobs and have therefore left for Serbia, already home to tens of thousands of displaced Roma.

Despite these alarming statistics, reintegration policies in Western Balkan countries are woefully inadequate when it comes to Roma returnees. So are measures to keep people from migrating to Western Europe in the first place.

Informal migration — be it short-term or long-term — has considerable disadvantages. It hinders the integration of marginalised communities, either in their host countries or in their countries of origin. It does not provide for social security or long-term planning. This in turn can affect children — when it comes to regular school attendance, for example. In light of current political developments in Western Europe, “labour migration” between the Western Balkans and Western Europe will become more and more formalised, which could lead to new challenges for Roma to make a living.

In Germany, for instance, experience shows that Roma are the last to benefit from the Western Balkan Regulation that should allow legal labour migration for people who might otherwise have applied for asylum. When analysing migration, demographic developments and strategies to fill the widening gaps in local workforces, experts and governments in the Western Balkans should understand the need to promote the inclusion of Roma in the labour market. In cooperation with companies, they should provide Roma with more opportunities to participate in quality vocational training.

However, this requires a long-term approach that not only combats antigypsyism in the labour market but also in schools and in society at large. This approach should give Roma students the tools and opportunities to finish school with adequate knowledge and skills so they can compete for places on vocational training programmes or enter further education.

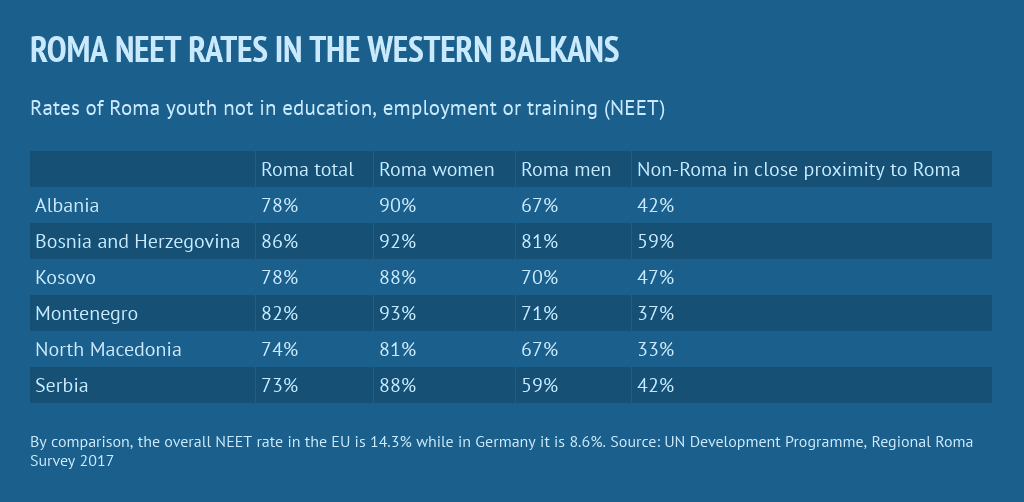

And it should give them equal opportunities to access the labour market — and not only in low-skilled positions or in the NGO sector. When we look at rates of Roma youth not in education, employment or training (NEET) in the Western Balkans, we see the total failure and ignorance of policies. We also see that we stand to lose another generation of young Roma.

However, this devastating data could also be read in a different way: all the countries of the Western Balkans as well as the European Union should invest more to make use of the potential of these young people and provide them with quality education and access to working opportunities.

Tim Judah says in one of his articles that in Romania “previously marginalised Roma are getting jobs that they would have been excluded from in the past”. This would be possible in the Western Balkans too, if governments, companies, experts and thinkers would promote such an approach. And yet, all the available data indicate that Roma are not affected by the demographic decline of ageing societies. They are, in fact, a very young population. The consequences of these two parallel developments should be taken into account by serious governments and thinkers.

Judah finishes the article with the sentence: “It needs action and ideas, not just from governments and thinkers in the countries whose populations are shrinking, but across Europe before the imbalance of what is happening becomes yet another issue threatening our liberal democratic foundations.”

I would like to finish this article with an addition: It needs urgent action to combat antigypsyism in these countries and open up opportunities for equal participation for Roma in education and labour markets. If current policies do not change quickly, the proportion of people will increase who are excluded from mainstream society, who face daily racism and who have no equal access to education or labour market. It is the duty and responsibility of the European Union and the countries in the Western Balkans to put an end to this state of affairs, which is threatening our liberal democratic foundations.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN or ERSTE Foundation.

First published on 30 January 2020 on Reportingdemocracy.org, a journalistic platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.

This text is protected by copyright: © Stephan Müller / Reporting Democracy. If you are interested in republication, please contact the editorial team.

Copyright information on pictures, graphics and videos are noted directly at the illustrations. Cover picture: Roma children at day-break in a settlement near Sarajevo in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photo: © Fehim Demir / EPA / picturedesk.com